Free, Melania develops a sustained inquiry into how a public figure can be simultaneously hyper-visible and structurally unknowable, and how a biographical account can remain evidentially responsible under such conditions. Its governing ambition is to reconstruct Melania Trump’s practical agency—within marriage, media, and the institutional architecture of the first lady’s office—without dissolving that agency into either sentimentality or caricature. The book’s distinctive value as an object of study lies in its method: it treats guardedness, silence, and aesthetic self-presentation as not merely obstacles to knowledge, but as the very material through which a modern political spouse exerts power, manages risk, and stabilizes a life-project. What results is a biography that repeatedly tests its own epistemic limits while still insisting on determinate claims when the text’s sources and internal criteria permit them.

The work instructs the reader, before any substantive narrative begins, in a disciplined posture toward what can be claimed. The epigraph from Michel de Montaigne—“Nothing is so firmly believed as that which we least know.”—does more than decorate the threshold; it operates as an epistemological warning that becomes retrospectively legible as the book’s guiding constraint. Throughout, Bennett’s prose remains attentive to the peculiar structure of belief around Melania Trump: the more aggressively a public demands psychological transparency from a figure who withholds it, the more quickly conjecture hardens into “knowledge.” The book’s opening movement is therefore less a promise of revelation than a pledge to distinguish, with care, between what is evidenced, what is reported, what is inferred, and what is simply projected.

This stance is sharpened by a paratextual decision that is presented as ethical and methodological at once: the author’s note announces that Barron Trump largely does not appear, and the reason is explicitly stated as a norm about children and public scrutiny. The note marks the book’s first explicit rule of inclusion and exclusion. It is also an implicit thesis about biography’s legitimate scope under conditions of celebrity power: the proximity of a child to public office does not automatically convert the child into admissible evidence. The constraint functions as a model for how other kinds of privacy are handled. It shows the reader that omission can be a method, and that a “complete” account is, in this genre, a temptation to be resisted.

Within that self-imposed boundary, the introduction frames the first lady’s role as an institutionally undefined position saturated by contradictory social expectations. Bennett does not treat this as a sociological curiosity; she treats it as the structural predicament that organizes the subsequent argument. The first lady is expected to be exemplary without formal authority, expressive without partisanship, intimate without impropriety, independent without disloyalty. The text offers a metaphor reported from Frank Bruni—first lady as hood ornament, or as topiary—that functions as an analytic baseline: the role tends to be conceived as ornamental, thereby inviting a persistent misreading of any action as either trivial or illegitimate. Melania Trump enters the book, conceptually, as the figure who both intensifies and exploits this contradiction. She is presented as “private and guarded,” a “fortress,” a “secretive” presence that elicits theories precisely because she refuses to supply the usual materials—unscripted vulnerability, performative warmth—by which the public calibrates sincerity. The work’s key early claim is that this secrecy is not merely temperamental; it is functional. It generates anxiety, but it also produces a kind of immunity: a person who does not trade in confessional access cannot easily be disciplined by the withdrawal of affection from the audience.

This functional account of secrecy becomes a recurrent operator. The book repeatedly returns to the idea that Melania Trump “speaks” through carefully controlled channels, and that her quietness is compatible with, and sometimes constitutive of, practical influence. The introduction already sketches a set of claims that the later narrative will progressively qualify and specify: Melania is portrayed as uniquely able to contradict Donald Trump without suffering the retaliation that others in his orbit risk; she is portrayed as willing to advise, to warn, to judge trustworthiness inside the White House; she is portrayed as guided by intuition rather than by inherited scripts of first-lady comportment. The text also introduces, as a conceptual provocation, the possibility of an “unlikely feminist” logic to this refusal of the role’s norms—an argument that will remain tense because it must hold together two heterogeneous claims: that Melania resists externally imposed expectations, and that she does so from within the materially privileged space afforded by marriage to a president.

From the start, then, the book’s internal movement is less a chronological accumulation of episodes than an iterative tightening of categories: privacy, agency, performance, institutional constraint, and the special form of power that can accompany apparent passivity. This is why the early emphasis on the first lady’s job-description matters. Once the role is treated as structurally contradictory, Melania’s behavior becomes legible as a strategy of survival within an incoherent institution, rather than as an idiosyncratic psychological riddle that biography must solve by speculation. The book’s principal wager is that one can reconstruct agency without granting oneself privileged access to interiority.

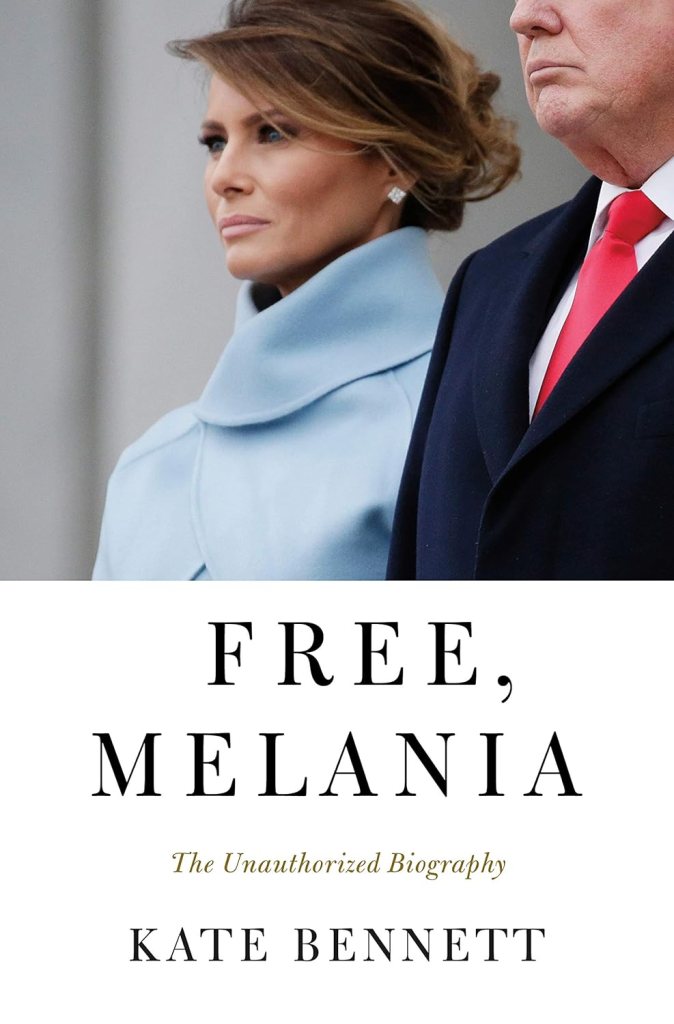

That wager is immediately tested by the first major scene through which the work chooses to introduce Melania Trump as a public actor: the 2016 Republican National Convention speech and the ensuing plagiarism controversy. The speech episode functions as an epistemic laboratory. Here, the evidence is comparatively public and determinate: the text describes that parts of the speech were taken from a speech delivered earlier by Michelle Obama (a claim reinforced by the photographic caption apparatus, which explicitly states this). Around that determinate core, however, a cloud of agency-questions forms: who wrote the speech, who approved it, who knew, who bears responsibility, what does responsibility mean in a campaign environment where speechwriting is collaborative and where candidate-spouses are often treated as symbolic extensions of the candidate rather than as accountable speakers? Bennett’s handling of this episode is methodologically revealing because she treats the scandal as more than a media cycle. It is presented as the first clear instance in which Melania becomes visible as a person whose public actions can generate political consequences, and whose relationship to those consequences cannot be reduced to simple puppet-theories.

The book stages, in this opening cluster, a recurring tension between two interpretive habits that it seeks to discipline. On one side lies the inclination to treat Melania as an empty surface—beautiful, silent, interchangeable—onto which campaign professionals project text and image. On the other side lies the inclination to treat her as a covert mastermind whose silence is itself evidence of intricate plotting. Bennett’s narrative pressure falls on both habits. She uses named figures involved in the response—Meredith McIver is prominently present as a speechwriter who takes responsibility—to show how institutional accountability is performed in such crises, and she simultaneously keeps Melania’s role from collapsing into pure absence by tracking what the episode reveals about her standards of control, her tolerance for risk, and her willingness to endure public humiliation while preserving private composure. The speech controversy thereby becomes a template for later episodes: an event in which Melania’s public reticence provokes interpretive overreach, while the book insists on a narrower, evidence-bound reconstruction of what can be said.

A further layer of the book’s internal argument emerges here: the relationship between authorship and persona. The controversy forces the reader to confront a basic problem: if Melania’s public speech can be partly borrowed, then the public voice attributed to her is, at least sometimes, an artifact produced by others. Yet the scandal also demonstrates that this artifact has real effects, and that those effects rebound onto Melania as if she were fully the author. The book treats this as a constitutive predicament of the political spouse: she is expected to “be herself” in public while the mechanisms of production that generate the public “self” remain distributed and strategic. A philosophical implication follows (and I mark it explicitly as an inference supported by the book’s recurrent emphasis on scripts, persona, and control): the political spouse’s identity, as an object of public knowledge, is structurally entangled with institutions of textual and visual manufacture, so that sincerity becomes less a property of inner feeling than a contested attribution within a media ecology. The text does not present this as theory; it presents it as the practical condition under which Melania’s actions must be read.

The second major conceptual cluster, introduced early and thickened through repeated return, concerns reluctance and consent. The work repeatedly describes Melania as a “reluctant” campaigner and as a person who appears to ration her participation. This is not treated as laziness; it is treated as a governance of exposure. The book’s argumentative responsibility here is delicate: it must describe a pattern—delayed moves, limited interviews, controlled appearances—while avoiding the illicit step of converting that pattern into a full psychology. Bennett therefore tends to anchor the claim in operational details: how the campaign and later the White House schedule her, how her staff manage press, how her presence is negotiated around family considerations, and how Donald Trump himself is portrayed as addressing her in ways that illuminate the marriage’s public economy (the introduction’s repeated quotation, “Smile, honey. You’re rich and beautiful,” functions as an emblem of how affection, instruction, and objectification can blur).

The book’s early movement then passes through another crisis event that operates as a second laboratory for its method: the release of the Access Hollywood recording, which the text treats as a shock to the campaign and, crucially, as a shock with a specific intimate valence for Melania. The episode is handled as a point where the book’s categories of privacy and publicness collide. The evidence here is again public (the existence and content of the recording is widely discussed within the narrative), yet the question that matters for Bennett’s argument is how such a public event reconfigures private relations and institutional standing. The book repeatedly emphasizes that commentators tend to frame Melania’s reactions in romantic terms—hurt, betrayal, humiliation—while missing that she occupies a structurally unique position: she can rebuke, distance, or discipline without being easily ejected from the orbit. The narrative’s insistence that Melania is “untouchable” gains traction in precisely such moments, where others fear retaliation and she can afford friction.

This is also where the book’s recurring theme of control without confession begins to acquire sharper determinations. Melania’s power is repeatedly described as a power to withhold: withholding spontaneous emotion, withholding interpretive keys, withholding access, withholding the kind of public suffering that would allow others to narrate her as victim or saint. The result is a figure who is hard to moralize about, and Bennett treats this hardness as part of the phenomenon rather than as a deficit to be remedied by imaginative empathy. The book thereby disciplines a common biographical impulse: to “humanize” by inventing interior scenes. Bennett’s restraint is not absolute—she recounts reported reactions, tensions, conversations—but the text repeatedly signals the difference between reported material and speculative filling.

When the narrative turns to Melania’s Slovenian origins, the book’s earlier categories are reconfigured rather than replaced. The chapter title “The Girl from Slovenia” is not merely geographic; it is functional. It introduces a second axis of interpretive temptation: the reader’s desire to explain the present by an origin-story. Bennett’s text both supplies and limits this desire. It reconstructs childhood and adolescence in Sevnica, references Yugoslav socialist conditions and the local texture of life, and presents family figures—parents, sister—in ways that stress formative lessons about appearance, work, and aspiration. Yet the book’s method remains consistent: when the evidence is anecdotal (childhood friends, local recollections), the narrative tends to present it as such, and when it is institutional (modeling pathways, immigration procedures, career steps), it treats it with a more documentary tone.

A central tension becomes visible here: the relationship between communist or socialist-background narratives and the book’s later portrait of Melania as a practitioner of self-branding and personal enterprise. The text provides enough material to support a reading in which Melania’s pursuit of security and her careful management of exposure are historically conditioned: a life formed within a system where resources are mediated by institutional power may yield a distinctive sensitivity to dependence and vulnerability. However, the book also resists crude determinism. It repeatedly emphasizes individual drive, aesthetic discipline, and a practical intelligence about advancement. The work therefore treats “Slovenia” less as an explanatory essence than as a reservoir of determinations—family habits, cultural styles, early experiences of constraint and aspiration—that later episodes can activate in new ways.

Here the title Free begins to show its conceptual ambition. The book does not present “freedom” as an abstract political concept; it presents it as a lived project of self-placement within systems of dependence. The narrative repeatedly returns to Melania’s desire for autonomy in contexts where autonomy is never pure: the modeling industry, immigration, marriage into wealth, entry into political spectacle, residence in the White House’s institutional labyrinth. Bennett’s reconstruction suggests that Melania’s “freedom” is typically pursued through control of boundaries rather than through public declaration of principles. She becomes “free” by managing who can see, who can speak, who can claim intimacy, who can impose tasks. The book’s central conceptual inversion (again, an inference grounded in the text’s repeated linkage of privacy, control, and survival) is that withdrawal can function as a positive capacity, a form of action suited to environments where direct assertion triggers punishment.

As the book turns to the relationship with Donald Trump—chapters titled “The Donald,” “The Girlfriend,” and “The Business of Becoming Mrs. Donald Trump”—it continues to resist psychologizing romance, and instead treats courtship and marriage as a mixed structure in which affection, status, transaction, and mutual instrumentality coexist. Bennett repeatedly describes how Melania is positioned socially: as a model in New York, as a glamorous companion within Trump’s world, as an object of fascination and rivalry. Yet the narrative’s deeper insistence is that Melania is not merely positioned; she positions herself. The language of “business” in the chapter title is an explicit cue: becoming Mrs. Donald Trump is treated as a process with negotiations, constraints, and strategic decisions, rather than as a purely sentimental culmination.

The work’s treatment of the wedding—“The Wedding of the Century”—further clarifies this analytic stance. Such an event invites spectacle, and the book uses the spectacle to clarify how Melania’s persona is constructed: through clothing, through guest-lists, through magazine coverage, through the conversion of private ceremony into public brand. Yet the narrative also keeps asking what agency looks like within such spectacle. Melania’s role is not simply to be displayed; she is portrayed as choosing, curating, consenting to particular forms of exposure. The book thereby extends its earlier problem of authorship into a broader register: the authorship of one’s public life when that life is co-produced by media, wealth, and other people’s desire to narrate.

The chapters that turn toward the family structure—“Family First, First Family” and “Just Melania”—tighten the book’s core tension between role and person. The first lady is a role without constitutional office, but it is also a lived position embedded in marriage and parenting. Bennett’s author’s note about Barron becomes, retroactively, part of this tension’s handling: the book wants to treat Melania as a mother and to show how motherhood factors into decisions (including decisions about residence and public presence), while refusing to treat the child as a narrative instrument. The result is an account that repeatedly gestures toward a private center—maternal concerns, family loyalties, protective instincts—while respecting the boundary it has declared. This declared boundary, in turn, shapes how the reader interprets what is included: when Barron appears, it signals that the author believes the episode directly illuminates Melania’s agency as mother rather than merely satisfying curiosity.

When the narrative arrives at “The White House,” the book’s earlier categories undergo a decisive transformation. Up to this point, privacy can seem like a personal style. Inside the White House, privacy becomes an institutional practice: who controls access to the first lady, who can schedule her, who can speak for her, how the East Wing mediates between residence, staff, and public. Bennett’s distinctive expertise—explicitly stated in the “About the Author” paratext as a journalist whose beat is the first lady and Trump family—becomes methodologically relevant here. The text begins to read less like celebrity biography and more like organizational ethnography: staff hierarchies, communications protocols, rivalries between East and West Wing, the peculiar economy of loyalty within a presidency marked by rapid turnover.

The book’s internal claim is that Melania’s “independence” is not merely a temperament but a mode of governance within this organization. In “A Most Independent First Lady,” the narrative insists that Melania does not simply obey inherited templates; she selects causes, declines events, delays moves, and constructs a platform (Be Best) that is presented as an attempt to give her tenure a public-facing mission. The text describes the platform’s facets (it explicitly notes three) and treats the platform as an artifact that reveals how Melania manages the contradiction introduced at the start: a role expected to “do something” but disciplined when it does too much. Be Best functions in Bennett’s argument as a compromise formation: it supplies a cause that is sufficiently universal to avoid open partisan conflict, and it allows Melania to act without surrendering the guardedness that defines her public stance.

At the same time, the book does not allow the platform to settle the question of agency. It records skepticism, awkwardness, and the friction between the platform’s simplicity and the complexities of the political context in which it is deployed. The work’s tension-sensitivity is visible here: even when Melania acts, she acts through an institution that expects symbolic performance, and symbolic performance invites cynicism. The narrative does not resolve this cynicism by pleading sincerity; it reconstructs how Melania’s staff seek to manage optics, how the first lady’s choices are read by allies and critics, and how the platform’s meaning shifts depending on whether one treats it as moral mission, public-relations necessity, or personal shield.

A second decisive tension enters through the chapter “Cordial, Not Close,” which treats relationships inside the first family and its extended political apparatus, especially with Ivanka Trump, as structured by proximity without intimacy. The title itself is an interpretive operator: it tells the reader to expect a distinction between outward politeness and substantive alliance. The book thereby extends its analysis of persona beyond Melania: it suggests that in this environment, social relations are frequently performed, and the performance can be sincere at the level of manners while strategically empty at the level of trust. The narrative uses repeated accounts of scheduling conflicts, public appearances, staff rivalries, and competing claims to influence to show that “family” within the White House is not simply kinship; it is an administrative and symbolic structure with resources to be contested.

This is where Bennett’s recurring emphasis on loyalty becomes philosophically significant. “Loyalty” is not treated as an ethical virtue in the abstract; it is treated as a currency within a precarious organizational field. The East Wing becomes legible as a domain where loyalty is demanded and enforced, where staff are protected or sacrificed, and where Melania’s power partly consists in her capacity to hire, fire, and reorganize. The later chapters “The Firing Squad” and “The East Wing, the White House’s Tightest Ship” intensify this theme. Here the narrative describes rapid personnel changes, internal battles, and the practice of scapegoating. Even the metaphor of a “tight ship” is conceptually loaded: it implies discipline, hierarchy, operational control, and a resistance to the chaos often associated with the West Wing in this presidency’s public image.

In these chapters, the book’s earlier claim that Melania is “untouchable” receives institutional grounding. Untouchability is recast as a structural protection afforded by marital status and by the symbolic sanctity of the first lady role, even in an administration that breaks norms. Melania can punish staff or shield staff, and she can do so with fewer consequences than others. The narrative repeatedly suggests that her ability to enforce boundaries is recognized by those around her, and that this recognition shapes behavior: people fear her displeasure, seek her favor, or attempt to circumvent her gatekeepers. The book thereby frames Melania as an actor within a micro-politics of access, where influence is mediated less by formal office than by proximity and trust.

A philosophical pressure point emerges here, and the book itself supplies the materials that generate it. If Melania’s power is largely a power of boundary management, then her agency appears primarily negative—refusal, withdrawal, veto, delay—rather than positive—legislation, policy, public argument. Yet Bennett repeatedly attributes to her concrete interventions: she is described as opposing the family separation policy at the border; she is described as treating the opioid crisis as an emergency requiring funding; she is described as warning Donald Trump about untrustworthy figures around him. These claims function as the book’s attempt to move from boundary management to substantive influence. The tension is that such influence is often difficult to verify with the same determinacy as public actions. The book navigates this by attributing such claims to reported conversations and by embedding them within broader patterns of behavior: Melania’s willingness to speak privately against the grain, her capacity to do so safely, and the observed consequences in staffing or messaging that align with her reported stance.

The work’s internal coherence depends on how it manages this transition from public evidence to private report. Bennett’s narrative repeatedly signals sources—sometimes named, sometimes described by role—and the book’s overall method is to accumulate converging reports across contexts, allowing the pattern itself to bear some argumentative weight. This is a distinctive inferential structure: instead of a single decisive document, the book often relies on the repetition of a behavioral logic across episodes. The reader is asked, implicitly, to accept that an agent’s character can be reconstructed not by accessing inner confession but by tracking how she consistently manages similar problems: risk, exposure, loyalty, and insult.

This inferential structure also governs the book’s treatment of the marriage, which becomes explicitly thematic in “The Marriage” and is further sharpened by “A Room of Her Own.” Here the narrative is under maximum interpretive pressure because the public’s desire is precisely to know whether Melania is happy, trapped, calculating, loving, contemptuous, or indifferent. Bennett’s text repeatedly warns against simplistic romance readings, while still acknowledging that the marriage is a site where politics, money, family, and intimacy intersect. The concept of “a room of her own” functions as more than a spatial detail; it suggests an architecture of separation within togetherness. The book uses the physical and institutional arrangement of the White House—residence, East Wing, private quarters, travel logistics—to show how a marriage can be publicly unified while privately segmented.

This segmentation becomes a key to the book’s concept of Melania’s “freedom.” Freedom appears, in the work’s internal logic, as the achievement of separateness without rupture. Melania is portrayed as preserving the marriage’s public form while insisting on private boundaries, sometimes through physical distance (the narrative treats her delayed move into the White House as an exceptional, meaning-laden decision), sometimes through controlled participation in political rituals, sometimes through the delegation of communication to staff. The philosophical interest here lies in the way the book treats freedom as compatible with dependency: Melania’s autonomy is exercised within a relationship that supplies wealth and status, and within an institution that supplies visibility and constraint. The book’s portrait therefore invites an account of freedom as practical sovereignty over one’s mode of appearing, rather than as independence from all relations.

The narrative’s attention to health—“A Health Crisis”—introduces a further complication. Health events have a special epistemic status in political life: they often generate official statements, press choreography, and a struggle over what the public is permitted to know. Within the book’s system, a health crisis becomes another test-case for the logic of privacy: does guardedness persist under vulnerability, and if so, how is vulnerability managed as an event? Bennett treats such episodes as moments where the first lady’s bodily reality intersects with the institutional demand for narrative control. The reader is again led to distinguish between public statement, press management, and the private experience that remains largely inaccessible. The episode therefore reinforces the book’s methodological restraint: even where the phenomenon is intimate, the permissible claims remain bounded by the text’s evidentiary discipline.

The late chapter “The Fashion” is structurally decisive because it retroactively re-determines the sense of many earlier episodes. From the beginning, the book has treated clothing and appearance as crucial to first-lady performance and as a site of impossible expectations. In the photographic apparatus, fashion is treated as documentable fact: captions specify designers, occasions, and costs (for example, a caption notes a Michael Kors runway show and later usage, including a sequined suit at a joint address). Within the narrative proper, fashion becomes a language whose semantics are contested. Bennett reconstructs how outfits are selected, how messages are attributed, how symbolism is read into clothing whether intended or not. The notorious border-visit jacket with the printed phrase (the book reproduces the phrase) becomes, in the text’s own terms, a paradigm: clothing as a medium that can overwhelm the stated purpose of an event, forcing interpretation to fixate on surfaces that nonetheless carry real political meaning once circulated.

What matters for the book’s inner argument is that fashion is presented as one of the few arenas where Melania’s agency is publicly visible without requiring speech. The work repeatedly portrays her as a person who understands the media and can manipulate it, and fashion is one of the principal mechanisms through which such manipulation can occur. Yet this also generates tension: if fashion is treated as expressive action, it becomes tempting to treat every outfit as deliberate message. The book does not fully dissolve this temptation; rather, it manages it by oscillating between competing readings, presenting the staff work behind clothing decisions, and showing how the same outfit can be read differently by different audiences. In doing so, the narrative again returns to Montaigne’s warning: belief rushes in where knowledge is thin. Fashion intensifies this because it invites semiotic overproduction: everyone becomes an interpreter, and interpretation is easily mistaken for proof.

The final chapter, “The Melania Effect,” functions as the book’s attempt to name the overall pattern that has been accumulating without being explicitly theorized. The “effect” is not presented as a single measurable outcome; it is presented as a composite of how Melania’s presence alters the behavior of others, the media ecology around the administration, and the symbolic configuration of the first lady role itself. Bennett’s core claim is that Melania’s combination of secrecy, discipline, and selective intervention produces a distinctive kind of influence. She does not lead by constant visibility; she leads by scarcity. She does not provide interpretive ease; she compels interpretation while refusing to ratify it. She thereby alters the terms on which the public relates to a first lady: the public cannot rely on confession, so it seeks signs; the book then reconstructs how those signs are produced, circulated, and sometimes strategically exploited.

At this point, there is structurally within the book first the tension between opacity and knowledge. Bennett wants to know and to show, yet she also constructs opacity as part of the phenomenon, and she repeatedly warns that opacity generates false certainty. The unity the book achieves here is a controlled discipline: it does not claim to dissolve the enigma; it claims to describe the practices through which the enigma is maintained and becomes effective. Second, there is the tension between agency and dependence. Melania is portrayed as unusually independent within her role and marriage, yet her independence is inseparable from the protections and resources the marriage supplies. The book stabilizes this tension by treating freedom as boundary sovereignty rather than as isolation. Third, there is the tension between ornament and actor. The introduction’s hood-ornament metaphor sets the baseline; the narrative seeks to show that Melania is not merely decorative. The book’s resolution is partial and methodological: it does not elevate her into a conventional policy actor; it reconstructs a different mode of power appropriate to her institutional position—control of access, discipline of staff, selective counsel, and symbolic messaging through presence and style.

Finally, there is the tension between feminism and the first-lady role. The book introduces the idea of an “unlikely feminist” logic in Melania’s defiance of expectations. Over the course of the narrative, this claim is repeatedly pressured by the realities of her situation: her marriage to a powerful man, the performative demands of the role, the aesthetic economy that frames her value in public. The work does not fully reconcile these pressures into a single doctrine. Instead it attains a layered stratification: Melania’s defiance can be read as a demand to be exempt from gendered expectations, while simultaneously remaining entangled with systems that profit from those expectations. The book’s philosophical unity, by its end, is therefore best described as a disciplined reconstruction of a form of agency that operates through controlled appearance, strategic silence, and institutional boundary work, while leaving intact—deliberately, because the evidence cannot authoritatively close it—the deeper question of how far such agency amounts to liberation, and how far it remains a sophisticated practice of survival within dependency.

Leave a comment