The Kritische Studienausgabe (KSA) of Nietzsche’s Sämtliche Werke presents Nietzsche’s philosophy as to be best read as a complete documentable sequence of textual operations—publication, revision, self-retrospective framing, and posthumous drafting—whose conceptual force depends upon philological exactitude and chronological intelligibility. It fuses, within one portable architecture, the biblical works Nietzsche authorized for print, with the Nachlass (posthumous papers) presented under strictly chronological principles, while preserving the material heterogeneity of notebooks, larger “hefte,” loose leaves, and layered manuscripts. The edition renders Nietzsche’s thought as an immanent history of its own production: a system of positions that emerge, congeal, and are repeatedly transposed through later prefaces, revised editions, and competing compositional strata.

Each volume is text and page identical with the corresponding KSA volume first issued as a paperback edition in 1980, prepared on the basis of the larger Kritische Gesamtausgabe edited by Giorgio Colli and Mazzino Montinari (de Gruyter, beginning 1967), and then “durchgesehen” (revised/checked through) for the second edition in 1988. This signals, first, that Nietzsche’s text is here treated as an object whose identity is stabilized by a critical apparatus lying behind the study edition; second, that the “study” format is not a mere pedagogical abridgment, but a deliberate transposition of the philological object into a form whose coherence is chronological and typographical, rather than interpretive. One reads Nietzsche here under an implicit discipline: the discipline of a text that refuses to be reorganized into doctrine by editorial systematization, since the editors explicitly renounce “jede systematische Anordnung” in the publication of posthumous fragments, privileging temporal succession.

The edition’s macro-structure divides the corpus into two great regimes: (1) works Nietzsche himself “herausgegeben” (brought out, authorized for publication), and (2) the Nachlass fragments spanning 1869–1889, distributed by year-ranges across multiple volumes, with an additional introduction/commentary volume and a chronicle/concordance/index volume “eigens … erstellt” for the KSA, including a concordance to the Kritische Gesamtausgabe.

This architecture forces a question that the edition neither resolves nor permits the reader to evade: what kind of unity is a “complete works” when the “work” (as completed, public, rhetorically shaped) is continuously haunted by a mass of drafts that are neither merely preparatory nor simply discardable, and when Nietzsche’s own late practice systematically revisits earlier works through new prefaces and retroactive reinterpretations? In the KSA, the unity of Nietzsche’s thinking is presented less as an achieved system than as a sequence of self-corrections whose textual markers—new editions with new prefaces, rearranged bindings, appended self-criticisms—function as internal transmutations of prior philosophical claims.

Volume 1 makes this dynamic explicit at the threshold by binding together a canonical early publication with a cluster of texts that press upon it from both sides: forward, through later self-criticism; backward, through drafts and philological precursor-essays. The volume contains Die Geburt der Tragödie aus dem Geiste der Musik (first issued 1872 and subsequently reissued under variant titling) together with the Versuch einer Selbstkritik attached to the “new edition” of 1886, alongside the four Unzeitgemäße Betrachtungen and a large dossier of “nachgelassene Schriften” from the Basel period (lectures, essays, private prints, and unfinished works). The editorial note stresses the decision to present, “an einer Stelle,” all treatises preceding the final form of Die Geburt der Tragödie, even at the cost of repetition, including a private print whose content substantially reproduces sections of the published book. This local editorial decision encapsulates the KSA’s global philosophical wager: Nietzsche’s “final” formulations are to be read in the light of their textual genesis, and genesis is to be presented as a plurality of nearly-identical textual events rather than as a single linear trajectory.

From within this frame, Nietzsche’s early thought appears as a problematic triangulation of aesthetic metaphysics, cultural diagnosis, and philological technique. The published Geburt der Tragödie advances a claim about Greek tragedy that is at once historical, psychological, and metaphysical in its ambition, treating the tragic artwork as an event in which the drives of form and excess achieve a precarious synthesis. Yet the volume refuses to allow this claim to settle as an “origin story” for Nietzsche’s later philosophy. The later self-critique of 1886, placed inside the same physical volume, functions as a retroactive destabilization: it compels the reader to treat the earlier book as an artifact whose philosophical posture is itself a symptom requiring diagnosis. The early essays and lectures intensify this destabilization by multiplying the conceptual paths into the tragic problematic: Socrates’ role, the relation of music drama to Greek culture, the meaning of Dionysian experience, the epistemic status of philology as a discipline that claims historical truth while handling interpretive fictions. The effect is that “tragedy” ceases to be a stable object and becomes a site where Nietzsche tests a method: how to speak scientifically about cultural origins while acknowledging that the very categories of explanation (reason, myth, aesthetic experience) are themselves historically constituted.

The Unzeitgemäße Betrachtungen deepen the methodological tension. Here Nietzsche’s cultural critique takes the form of strategically partial interventions—attacks on contemporary intellectual culture, reflections on the function of history for life, portraits of exemplary figures—whose argumentative rhythm is inseparable from their polemical genre. The KSA’s decision to keep these pieces within the early “works” rather than in the fragmentary regime places emphasis on their public intent; yet the surrounding Basel writings demonstrate how porous this boundary remains. The philosophical problem, as the edition’s structure forces it into view, concerns the relation between philosophical critique and the institutions through which critique speaks: university culture, journalism, the authority of scholarship, the prestige of “Bildung,” and the modern archive of historical knowledge. Nietzsche’s early practice already exhibits a paradox that later becomes systematic: he deploys scholarly forms (lecture, treatise, historical argument) to question the life-effects of scholarship itself.

In this early constellation, the short treatise Ueber Wahrheit und Lüge im aussermoralischen Sinne occupies a decisive position, precisely because it is presented as a “nachgelassene Schrift” within a volume dominated by printed works. Its presence signals that Nietzsche’s later epistemological suspicion—his analysis of truth as a function of metaphor, convention, and social stabilization—is neither an afterthought nor an abrupt rupture, but a subterranean line already running beneath the aesthetics-and-culture surface. The KSA’s organization thereby renders Nietzsche’s development as a set of overlapping temporalities: public publication dates, private drafting dates, and later editorial dates of revision and reissue. The “composition sequence” is no longer reducible to a single timeline; it becomes a braided structure in which later Nietzsche repeatedly re-enters earlier Nietzsche, not as an external commentator, but as a writer who edits the conditions under which his earlier claims can be read.

This internal re-entry becomes structurally dominant in the mid-period volumes, where “new editions” with added prefaces repeatedly interrupt the continuity of Nietzsche’s argument. Volume 2, containing Menschliches, Allzumenschliches I and II, explicitly marks this pattern: the first volume of the work appears with its 1878 origin while the KSA also registers the “Neue Ausgabe” bearing an “einführende Vorrede” in 1886; the second volume likewise carries the 1886 prefatory frame. Menschliches, Allzumenschliches is programmatically cast as a “book for free spirits,” and its textual form—aphoristic, fragment-like, serial—already approximates the logic of the Nachlass without relinquishing authorial composition. In KSA terms, it is a public text that mimics the laboratory conditions of notes. The philosophical consequence is substantial: Nietzsche stages thinking as a sequence of discrete perspectives whose unity is practical and experimental rather than deductive. Yet the later preface repositions this experiment, supplying a retrospective justification that reshapes the reader’s sense of what the aphorisms “were doing” at the time of composition. The KSA thereby makes visible a distinctive Nietzschean temporal reflexivity: the act of prefacing becomes a philosophical act, an intervention into the causality of one’s own intellectual history.

The volume also preserves, in Nietzsche’s own paratextual remarks, indications of compositional circumstances and intended gestures of intellectual homage. In the opening materials, Nietzsche frames the origin of the work in a specific locale and winter sojourn, associating it with a desire to offer “personal tribute” to a “liberator of the spirit” at a determinate date. Even when such remarks are read strictly as literary self-presentation, the inclusion of them within a critical framework enables a philosophically productive caution: Nietzsche’s texts consistently negotiate between conceptual claim and self-narration, between argument and the staging of intellectual lineage. The “free spirit” stance is thus never purely methodological; it is simultaneously a performative posture that positions Nietzsche relative to predecessors, contemporaries, and imagined successors.

Volume 3, bringing together Morgenröthe, Idyllen aus Messina, and Die fröhliche Wissenschaft, intensifies the interplay of genre, method, and self-retrospective framing. The volume registers Morgenröthe (1881) together with its “new edition” preface of 1887, and Die fröhliche Wissenschaft (1882) together with its expanded 1887 form including the appended “Lieder des Prinzen Vogelfrei.” This double dating is not merely bibliographic. It installs within the reader’s experience a philosophical image of thought as seasonal recurrence: a text is written, then later re-entered under altered physiological, intellectual, and polemical conditions. The 1887 preface to Morgenröthe describes the author as an “underground” worker—boring, digging, undermining—whose method is slow, deliberate, and quietly relentless. Here the metaphor is methodological: critique proceeds by excavation of moral “prejudices,” treating the apparent solidity of moral convictions as a surface phenomenon supported by concealed historical and psychological strata. But the metaphor also anticipates the editorial logic of the collection itself: the edition, by presenting chronologically stratified fragments and by preserving manuscript layers where a single notebook contains different times, literalizes the idea that thought is stratified, layered, and subject to later re-cutting.

The Fröhliche Wissenschaft materials sharpen the tension between joy and method, between experimental play and rigorous suspicion. The paratexts and mottos situate “gaya scienza” as a style of knowing in which experience is transmuted into insight without the solemnity of dogmatic philosophy; yet the text simultaneously implies that such gaiety arises from and depends upon prior suffering, constraint, and the long pressure of intellectual discipline. The KSA’s inclusion of later prefatory material again converts this into a problem of reading: the same aphoristic body is given a second interpretive horizon by the author himself. Nietzsche’s later voice claims to explain what the earlier book “means,” yet the very existence of this later voice raises the question of whether meaning is to be treated as the stable content of propositions or as the changing function of a text’s placement within a life-sequence of crises, recoveries, and renewed aggressions against inherited ideals. In KSA terms, the “work” is always more than its first publication, because Nietzsche repeatedly makes the act of republication a philosophical event.

Volume 4, containing Also sprach Zarathustra in its four parts, presents the most conspicuous case of publication sequence functioning as philosophical form. The KSA notes that the first and second parts appeared in 1883, the third in 1884, and the fourth and final part in 1885 as a private printing; it also records the later binding together of the first three parts in 1886 under a single title with the specification “in three parts.” Here the composition sequence and the public sequence diverge in a way that becomes interpretively decisive: the work’s internal architecture is not simply a planned totality released in installments; it is a developing textual organism whose later part (privately printed) occupies an ambiguous status between revelation and reserve, between public doctrine and selective dissemination. In consequence, Zarathustra can be read neither as a mere poetic interlude nor as the central doctrinal “system” of Nietzsche’s thought. It functions as a transformation of philosophical address: the philosopher becomes a dramatist of valuation, staging a teaching that repeatedly risks misunderstanding and repeatedly reconfigures its own audience.

The opening of Zarathustra, as printed, already dramatizes a philosophical economy of overflow, descent, and redistribution: a movement from solitary accumulation to the need to “give away,” from the height of contemplation to the descent into the human sphere. Yet the KSA’s framing discourages any quick extraction of theses from this poetic scene, because the work’s publication history itself signals instability of communicative intent. The private printing of the fourth part, followed by later recombinations, means that “the work” is materially multiple: different publics encountered different Zarathustras, and Nietzsche himself managed this multiplicity as a function of his philosophical strategy. The KSA, by making this explicit in its minimal editorial notices, shifts the interpretive burden back onto the relation between form and claim: if a philosophy requires a prophet-poet voice to articulate its critique of morality, metaphysics, and herd-values, then the philosophy’s “content” is inseparable from its rhetorical situation and its risk of misreading.

The translated afterword appended in the volume, originally written by Giorgio Colli for an Italian edition, further intensifies this caution by warning against the readerly impulse to treat Zarathustra as a reservoir of detachable doctrines. In KSA perspective, this warning becomes methodological: Nietzsche’s most “poetic” book is simultaneously his most technically philosophical in one decisive sense—it forces thought to confront the limits of propositional exposition when the object is the revaluation of values and the transformation of the subject who evaluates. The “teaching” is staged as a sequence of trials, reversals, and re-beginnings; the reader’s demand for doctrinal clarity becomes itself a symptom within the drama of valuation.

Volume 5, containing Jenseits von Gut und Böse (1886) and Zur Genealogie der Moral (1887), represents a reconfiguration of Nietzsche’s philosophical method into a form that is simultaneously more analytically aggressive and more self-conscious about the conditions of philosophical discourse. The preface to Jenseits von Gut und Böse thematizes truth, dogmatism, and the seductions of grammatical metaphysics; it frames earlier philosophy as a history of “dogmatisms” built upon inherited prejudices, folk-superstitions, and linguistic misdirections. In KSA context, this text operates as a displacement of earlier Nietzsche in two directions at once. It displaces the early aesthetic-metaphysical posture by treating metaphysical craving as a psychological and cultural phenomenon to be explained, not affirmed. It also displaces the mid-period aphoristic experimentation by sharpening the polemical target: the problem is no longer only the liberation of the individual free spirit from inherited ideals, but the exposure of the historical and physiological genesis of those ideals within European morality and metaphysics.

Genealogie then condenses this methodological turn into a distinctive scientific ambition: to provide “genealogical” explanations of moral concepts by tracing their origins, transformations, and the power-relations sedimented within them. The placement of Genealogie alongside Jenseits emphasizes that the genealogical method is not an isolated technique, but the maturation of a long-running tendency already visible in Morgenröthe: the tendency to undermine moral self-evidence by excavating its conditions. Yet Genealogie also risks displacing Morgenröthe retroactively by presenting itself as a more decisive and rhetorically structured intervention, with an intensified claim to historical explanatory force. The KSA, by retaining the earlier texts with their later prefaces, prevents this displacement from becoming a simple supersession. Instead, it invites a more exacting view: Nietzsche’s critique increasingly aspires to scientific hardness, yet it retains a form of experimental perspectivism that undercuts the finality of any explanatory narrative. Genealogy, in this light, becomes both a method and a problem: it seeks causal intelligibility while insisting that causality in moral history is inseparable from interpretation, struggle, and retrospective projection.

Volume 6, containing Der Fall Wagner (1888), Götzen-Dämmerung (1889), and a sequence of late writings composed between August 1888 and early January 1889—including Der Antichrist, Ecce homo, and the Dionysos-Dithyramben—makes the late Nietzsche appear as a concentrated crisis of critique and self-presentation. The editorial note is especially explicit about the intended publication sequence up to 2 January 1889, listing the works “in the order of their origin” and marking Nietzsche contra Wagner as a text whose publication Nietzsche renounced on that date, hence its placement as last in the sequence in the form he had then authorized. This explicit sequencing is philosophically weighty. It shows Nietzsche’s late production as an internally ordered campaign: an assault on Wagner, on “idols” of culture and morality, on Christianity, coupled with an autobiographical work that seeks to articulate the conditions under which such an assault could be intelligible as fate rather than mere polemic, and finally a lyrical intensification under the sign of Dionysus. The KSA thereby compels the reader to treat the late Nietzsche neither as a collection of isolated provocations nor as a final doctrinal synthesis. It is a sequence of interventions whose unity is strategic and temporal: the works form a chain in which each link amplifies and risks compromising the preceding one.

This late chain also renders visible a tension that runs through the entire KSA: Nietzsche’s philosophy repeatedly oscillates between analysis of valuations and performative creation of valuation. In Götzen-Dämmerung, the “hammer” is both a diagnostic instrument and a destructive tool; it tests idols and breaks them. In Der Antichrist, critique intensifies into condemnation under a title that already signals a deliberate re-siting of the philosophical voice relative to European religious history. In Ecce homo, Nietzsche presents the task of interpretation as inseparable from autobiography: the meaning of the works is tied to the kind of life that could have produced them. The KSA’s framing, by explicitly locating these texts within a narrow compositional window and by recording Nietzsche’s own publication intentions up to the threshold of collapse, makes the late style appear as a philosophical problem of method: how far can critique be intensified before it ceases to function as explanation and becomes pure act, pure posture, pure rhetorical force? Conversely, how can the creation of new values avoid collapsing into mere self-mythologization when it must speak in the first person about its own exceptional status?

At this point the second great regime—the Nachlass volumes—becomes conceptually indispensable. Even in the volumes available here (7–8, and the listing of later fragment-volumes), the editorial principles governing fragments disclose a philosophy of textual evidence: the editors commit to strict chronology, publish manuscripts in the sequence corresponding to their time of origin, and preserve orthography and punctuation wherever possible, marking unavoidable interventions in the underlying critical apparatus of the Kritische Gesamtausgabe. They also formalize a typographical semantics that carries philosophical consequences: single underlining becomes letterspacing, multiple underlining becomes bold-like emphasis (rendered here as half-bold in the German edition), editor additions appear in angle brackets, editor-supplied headings in square brackets, and lacunae/unreadables are explicitly signaled. The KSA thus teaches a readerly ethics: one must distinguish what Nietzsche wrote from what editors supply; one must respect the fragment as fragment; one must resist the temptation to smooth discontinuities into doctrine.

Volume 7, spanning fragments from autumn 1869 to end of 1874, already transforms the early Nietzsche by exposing the density of his preparatory work, his shifting projects, and the layered character of notebooks. Yet the most philosophically decisive point is the editorial concession that the principle of publishing manuscripts individually is restricted when a manuscript contains “Schichten aus verschiedenen Zeiten” (layers from different times), in which case layers are separated and published according to chronology. This is a direct structural analogue to Nietzsche’s own philosophical practice of retroactive revaluation. A notebook can contain multiple times; a concept can be written, then rewritten; a plan can be drafted, then hollowed out; the “same” textual space can host incompatible projects. The KSA thereby renders Nietzsche’s thought as stratified temporality: the present of writing is itself internally divided.

Volume 8, spanning fragments from beginning 1875 to end 1879, gives a further, almost schematic expression of Nietzsche’s planning consciousness. The editorial note specifies the material basis—35 manuscripts including larger notebooks, smaller notebooks, and folders of loose leaves—and again defers to the general principles stated in volume 7. Within the fragments themselves appear outlines and self-imposed production schedules, including sequences of projected thematic blocks—history, philosophy, antiquity, art, religion, school, press, state, society, nature, and a “path of liberation”—and calculations of output over years. These planning fragments are philosophically revealing in a way that the published works cannot be. They show Nietzsche treating his corpus as a temporal project whose unity is to be achieved through disciplined writing, yet whose content remains open, rearrangeable, and subject to strategic reconceptualization. The KSA’s chronological presentation means that the reader witnesses, at close range, how the “free spirit” program emerges from a field of competing outlines, abandoned emphases, and revised intentions. In this sense, the Nachlass displaces the printed work’s apparent completeness by supplying the evidence of its contingency and the plurality of paths that could have led elsewhere.

The effect across volumes 1–6 and the available Nachlass is a distinctive philosophical portrait of Nietzsche’s development: an early attempt to ground cultural critique in an aesthetic-metaphysical interpretation of Greek tragedy; a subsequent intensification of cultural diagnosis through untimely polemics against modern institutions of knowledge; a mid-period turn toward aphoristic experimentalism under the banner of the free spirit; a deepening into subterranean critique of moral prejudices; an eruption into a prophetic-poetic form that stages revaluation as a transformation of address and audience; and finally a late consolidation into genealogical analysis and maximal polemical intensity, culminating in a sequence of works whose publication intentions are themselves documented as part of the corpus.

Yet the main contribution is that this prevents this developmental sketch from hardening into a linear narrative of “stages.” The edition’s own material facts continually re-complicate any such story. Nietzsche returns to earlier works through new prefaces (1886, 1887), thereby reauthorizing them under new conditions and with altered interpretive cues. He releases Zarathustra in parts and manages its circulation through private print, thereby destabilizing the idea of a single public text. He composes, within a few months, a chain of late works that interlock polemic, diagnosis, and self-interpretation, while explicitly renouncing publication of one component at a determinate date—an editorial fact that becomes philosophically significant because it shows Nietzsche governing the boundary between authorized act and merely possible act. Meanwhile, the Nachlass volumes insist that behind every “work” lies a moving field of fragments whose chronology is the only permitted organizing principle, and whose typographic marking disciplines the reader against smoothing.

From this standpoint, we can discern that later Nietzsche replaces the earlier Nietzsche by retroactive framing; published Nietzsche shifts by the evidentiary weight of the drafts; analytic Nietzsche is displaced by the poetic Nietzsche, then poetic Nietzsche is replaced by a renewed analytic hardness in Jenseits and Genealogie; cultural critique is goes to physiological and genealogical explanation; explanation is replaced by condemnation; condemnation is displaced by self-presentation that claims to be the condition of intelligibility for the condemnation. The KSA’s structure makes these movements readable as textual facts rather than as speculative psychology. It also reveals that each move preserves what it displaces in a transformed form. The early tragic problematic persists as a question of art’s metaphysical function even when metaphysics becomes an object of suspicion; the untimely critique of historical scholarship persists as the genealogist’s suspicion toward moral historiography; the aphoristic laboratory persists as a discipline of perspectival thinking within later, more structured polemics; the poet-prophet persists as a rhetorical resource even when Nietzsche returns to treatise-like aggression.

If we try to read the collection of works with scientific neutrality, one must treat Nietzsche’s “philosophy” as a complex object composed of multiple kinds of warrants. There are warrants internal to argument (conceptual distinctions, causal hypotheses, historical narratives). There are warrants internal to genre (the authority claimed by polemic, by aphorism, by prophetic address, by autobiography). There are warrants internal to textual history (new editions and prefaces that reshape meanings; sequences of publication that regulate audience; manuscript layers that testify to temporal division within writing). The KSA is distinctive in that it supplies all three without offering a reconciliatory interpretive key. It gives the reader the evidence and the constraints.

If one asks what “system” remains under such conditions, the KSA suggests an answer by its very refusal to systematize: Nietzsche’s unity is methodological and diagnostic. The corpus repeatedly targets the mechanisms by which values become authoritative—through metaphysics, morality, religion, grammar, culture, and institutional knowledge—and repeatedly invents literary forms adequate to exposing those mechanisms. The unity lies in a practice: the practice of rendering the self-evidence of values questionable by tracing their conditions. Genealogy is one explicit name for that practice, yet the practice precedes the name and exceeds it, extending from early reflections on truth and illusion through the subterranean labor of Morgenröthe to the late sequence of 1888–89 where critique aims at the deepest collective valuations of European culture.

The KSA is designed to be navigated as a research instrument: it anticipates scholarly needs for cross-referencing, dating, and terminological tracking. In other words, it does not merely present texts; it embeds them within an apparatus of orientation that aims to make Nietzsche’s compositional life and textual variants operational for interpretation. Within the present materials, it foregrounds that Nietzsche’s corpus is an archive whose intelligibility depends upon systematic indexing, while its philosophical content persistently attacks the modern faith in system and the moralized prestige of “objective” knowledge.

What becomes legible, once the edition’s own compositional scaffolding is taken with full seriousness, is a distinctive economy of self-revision that is at once authorial and editorial: Nietzsche’s published books repeatedly fold earlier phases back into themselves through new prefaces, retitlings, and reorganized sequences, while the KSA’s philological architecture repeatedly folds the published books back into a wider field of drafts, abandoned plans, and temporally layered notebooks. The series thereby yields a double temporality—publication-time and writing-time—whose interference pattern is the edition’s most instructive philosophical object, because it compels every strong claim about “Nietzsche’s position” to be restated as a claim about textual formation under constraints (physiological, intellectual, polemical, and material), rather than as a detachable doctrine.

From the point at which the edition foregrounds the late “underground” labour of critique—already thematized in the prefatory rhetoric of Dawn as a practice of slow excavation, a sustained descent into the preconscious supports of moral valuation—the KSA makes it difficult to keep the familiar boundary between a “work” and its “preparatory materials” in place. In the Dawn–Gay Science complex, the text’s own presentation announces a method that oscillates between aphoristic incision and reflective orchestration: the work appears as a sequence of discrete interventions, yet it continuously generates internal cross-references, tonal recurrences, and self-correcting echoes that operate like a latent argument distributed across fragments. The edition’s presentation of these books in the same physical volume, together with the explicit indication that The Gay Science exists in a second, expanded configuration with added prefatory and concluding strata, renders the work’s identity itself a function of revisionary layering: what one calls “the book” is already a temporal composite of editions, supplements, and editorial decisions about where an addition becomes constitutive rather than marginal.

A particularly instructive tension, which the framing material allows one to pursue without importing external harmonizations, concerns the relation between equilibrium and excess in Nietzsche’s compositional practice. Colli’s translated afterword to The Gay Science (as included at the end of the volume) articulates a diagnostic contrast between an achieved “expressive peak” of balance in the earlier arrangement and the later additions that strain that equilibrium, exemplifying how Nietzsche’s own revisionary impulse can be described as an intensification that risks deforming the earlier poise of a constellation. This is philosophically consequential because it complicates any simplistic narrative of linear “maturation”: a later addition can be more programmatic, more confrontational, more explicit, and yet—precisely by that explicitness—less capable of sustaining the delicate internal counterweights through which an aphoristic book achieves its peculiar kind of unity. The KSA’s inclusion of such editorial reflections (translated from Colli’s Italian introductions) functions as a controlled interpretive pressure: it does not replace the text, but it stresses the issue of whether Nietzsche’s increasing conceptual audacity correlates with an increasing formal risk.

In this region of the oeuvre, the edition also clarifies how “free spirit” rhetoric—introduced and transformed across Human, All Too Human and its sequels—reappears in a new register as the ethos of inquiry, the disciplined refusal of inherited moral prejudice, and the cultivation of a perspective that treats its own cognitive instruments as suspect. The editorial Vorbemerkung to the Dawn–Gay Science volume situates the works within an explicit chronology of publication and republication (first editions and later “new editions” with prefatory framing), thus making the formal fact of revision into an intrinsic part of the evidence about method: Nietzsche repeatedly returns to earlier textual bodies to refit them for a new phase of the project, and the KSA thereby places the interpreter under an obligation to treat “Nietzsche’s critique” as an activity that retools its own earlier products.

The transition into Zarathustra is then presented, by the edition’s own apparatus, as an event that is simultaneously disruptive and continuous. On the one hand, the Vorbemerkung records a publication sequence that itself bears the marks of singularity—parts appearing across successive years, a final part issued as a private print, and a later binding-together of the first three parts—so that the work’s “unity” is materially staged as a delayed consolidation rather than as a given.

On the other hand, the translated afterword explicitly cautions against a reading that isolates Zarathustra as sheer rupture, insisting that thematic continuities can be traced back into The Gay Science and its associated unpublished fragments, while also stressing that the decisive issue is not merely “content” but the achievement of a form in which the work’s significance resides in detail, cadence, and the distribution of intensities rather than in deducible theses. The collection thereby offers an internally grounded way to articulate a difficult claim: Zarathustra can be treated as a displacement of the earlier “moralist and psychologist” voice by a prophetic-poetic mode, while the edition’s own framing indicates that this displacement remains internally conditioned by earlier analytic labour and reappears as material for later conceptual clarification.

This relation of recuperation becomes even more systematic when Beyond Good and Evil and On the Genealogy of Morality are read under the KSA’s stated compositional sequence. The Vorrede to Beyond Good and Evil—with its performative staging of dogmatism’s predicament and its reflexive attention to grammar, inherited metaphysical habits, and the seductive power of “final” philosophical architecture—constitutes an internal methodological manifesto: philosophy must become critique of its own instruments, including the linguistic micro-mechanisms through which metaphysical certainty is fabricated.

Here the collection’s organization assists philosophical interpretation by placing the “prelude to a philosophy of the future” adjacent to the explicitly polemical “treatise” on genealogy, thereby making visible that the critical task is pursued through two correlated procedures: conceptual reorientation at the level of philosophical style and strategic historical-psychological reconstruction at the level of moral origins. The edition’s translated afterword (again by Colli) goes further, articulating Beyond Good and Evil as a clarification and conceptual development of themes treated symbolically or lyrically in Zarathustra, while also characterizing this point as a kind of “end” and “closure” for Nietzsche’s internal experience of the project, after which the later works increasingly absorb him. Such a remark, because it is embedded in the series’ own apparatus, offers a warranted way to mark a structural turning-point: the movement from preparatory exploration toward a phase in which the texts no longer function as detachable “stages” but as an engulfing medium of self-interpretation and self-intensification.

At this juncture the KSA’s broader architecture—especially the inclusion of the posthumous fragments volumes governed by explicitly chronological editorial principles—retroactively alters the status of these “major” published works. For once the edition has insisted, in its Vorbemerkung to the early fragments volume, that the Nachlass is published according to strict chronological principles, forgoing any systematic arrangement by the editors and preserving manuscript order insofar as it can be reconstructed from Nietzsche’s own habits (including the materially telling habit of writing from back to front in notebooks), the interpreter cannot innocently read later systematic-sounding motifs as if they were always already intended as a finished doctrinal architecture.

The collection’s main rule—publish the manuscripts in their temporal sequence, separate layers where a single notebook contains strata from different times, keep orthography and punctuation in principle—converts the Nachlass into a field of temporal micro-evidence about the emergence, revision, and abandonment of conceptual projects. This affects the reading of Genealogy as well: the “systematic attempt” it embodies, with its sometimes pedantic or provocatively paradoxical accents (as Colli remarks), can be related to earlier exploratory drafts and later radicalizations, without presupposing a hidden book waiting to be assembled by editorial force.

The Kritische Studienausgabe, as a scholarly object rather than as a convenient compilation, is important precisely at this point: it constructs a disciplined resistance to the temptation to treat Nietzsche’s late vocabulary—will to power, eternal recurrence, overman—as if these were stable theoretical nodes that merely receive different rhetorical garments. The series’ own framing around Zarathustra warns against searching for a “theory” in the deductive sense and emphasizes the primacy of detail over system, while the Nachlass editorial principles institutionalize a refusal of systematic rearrangement by the editors. Together these elements encourage a method of reading in which conceptual motifs are approached as compositional events that migrate across genres and phases: they emerge as experimental intensities in notebooks, gain symbolic force in prophetic-poetic form, become targets of conceptual clarification and polemical sharpening in later published works, and then re-enter the Nachlass as further drafts, revisions, and tactical redeployments.

The late volume that gathers The Case of Wagner, Twilight of the Idols, The Antichrist, Ecce Homo, the Dionysus-Dithyrambs, and Nietzsche contra Wagner provides the most explicit editorial warrant for treating Nietzsche’s final phase as an accelerated concentration of production under a compressed temporal horizon. The Vorbemerkung does more than list contents; it states that the volume also contains “posthumous writings” composed between August 1888 and early January 1889, and it specifies which of these Nietzsche demonstrably intended to publish up to January 2, 1889, in the order of their origin. It further records that Nietzsche renounced publication of Nietzsche contra Wagner on that date, and that the text is therefore placed last in the sequence in the form he had approved up to that point. This editorial disclosure is philosophically weighty: it places the question of Nietzsche’s late “polemics” under the sign of authorial intention understood as temporally situated, revisable, and fragile. It also indicates that the boundary between “published work” and “posthumous writing” is itself subject to an internal dynamism: the category “posthumous” can arise from contingency and interruption, as much as from principled withholding.

Once this is granted, the late texts can be described—without recourse to melodramatic external narratives—as the site where Nietzsche’s critique turns increasingly toward self-accounting and toward a retrospective ordering of his own path. Ecce Homo is positioned in the volume as one of the writings intended for publication; within the KSA’s system it therefore appears simultaneously as a text among others and as an attempt at an authorial meta-frame. Yet the edition’s very arrangement prevents this meta-frame from functioning as sovereign. Because Ecce Homo is embedded within a sequence that includes polemical, diagnostic, and poetic utterances, and because the Nachlass volumes (by design) contest any systematic editorial construction of Nietzsche’s “final system,” the autobiographical self-interpretation cannot simply stabilize the oeuvre; it becomes one further textual force that competes with, and is re-situated by, other forces. The effect is a constructive complication: Nietzsche’s own retrospective narration is treated as evidence, yet the edition’s architecture ensures that it remains evidence situated within a broader field of textual production, not a master key that cancels the philological plurality.

Earlier, the collection stages how the Dawn–Gay Science ethos of subterranean work was replaced by the prophetic-poetic eruption of Zarathustra, and then how this prophetic-poetic register was refunctioned by the conceptual clarification and polemical sharpening of Beyond Good and Evil and Genealogy. In the late cluster, the move proceeds again: the careful analytic and genealogical procedures are drawn into a more immediate and aggressive rhetoric of diagnosis, where “philosophizing with a hammer” becomes a figure for a test that sounds idols, measures hollowness, and registers resonance.

Yet this late shift also produces a counter-movement: the texts repeatedly bring the problem of self-overcoming to the surface, sometimes explicitly naming it as the crucial moral-psychological achievement required of the philosopher. The KSA’s arrangement permits one to read this as a methodological knot: the critique of cultural decadence, of inherited religious-moral structures, and of aesthetic seductions is coupled to an insistence that the critic’s own historical embodiment—the fact of being “a child of the time”—belongs to the hardest internal struggle. In this sense, the late polemics do not simply accelerate earlier arguments; they reconfigure the epistemic stance of critique by binding it more tightly to the critic’s own physiological and historical conditions.

The Nachlass volumes (7–13) are not mere ancillary reservoirs of “extra material”, they are provided to serve as the edition’s internal mechanism for preventing the published books from merging into a pseudo-system that Nietzsche never finished and that earlier editorial traditions were tempted to fabricate. The explicit renunciation of “systematic ordering by the editors” in the presentation of fragments is the methodological analogue, at the philological level, of Nietzsche’s own repeated suspicion toward dogmatic “final” philosophical architectures at the conceptual level.

The edition thereby creates a productive alignment: the material method of publication mirrors a central philosophical motif in the work, namely the critique of the metaphysical craving for closure and the exposure of the linguistic and psychological forces that generate that craving. This alignment should not be romanticized as perfect identity—philological chronology and philosophical anti-dogmatism are distinct operations—but the KSA makes it possible to see how a critical edition can itself function as a philosophical instrument by structuring the conditions under which certain interpretive errors become harder to sustain.

A further tension emerges when one considers how the edition integrates translated Italian editorial afterwords (Colli) at the end of several volumes. These texts do not operate as a comprehensive interpretive regime; they appear as localized reflections attached to specific clusters (Dawn–Gay Science, Zarathustra, and the later pairings), and they often emphasize questions of form, continuity, and the risk of superficial valuation. Their presence introduces a second-order problem: the aims to remain grounded in the philological reconstruction of Nietzsche’s texts, yet it also acknowledges that certain interpretive problems—how to integrate Zarathustra into the whole, how to understand the relation between later clarifications and earlier symbolic forms, how to think the late phase as “absorption”—are inseparable from the very act of presenting the oeuvre in a usable configuration. The edition thus becomes a site where scholarship and philosophy intersect under constraint: it must offer tools and minimal frames that enable reading, while resisting the production of a final interpretive synthesis that would contradict both the philological evidence of revision and the conceptual thrust of Nietzsche’s critique.

If one now draws these threads together, a coherent picture of the publication emerges in the form of its methodology: Nietzsche’s oeuvre, as presented here, is best understood as a succession of experimental forms of critique—philological, cultural, psychological, genealogical, poetic-prophetic, polemical, and autobiographical—whose internal transitions are intelligible in function and stance, underwritten by concrete compositional sequences and by the material history of publication and revision.

The early Basel materials included in volume 1 (lectures, drafts, and short treatises alongside The Birth of Tragedy and the Untimely Meditations) show a mind still negotiating the relation between classical philology, aesthetic theory, and cultural diagnosis, while already developing a rhetoric of revaluation and a suspicion toward prevailing educational and intellectual institutions. Later, the “free spirit” books stage a retooling of critique toward more granular psychological and epistemic observations, and the subsequent volumes demonstrate how that granularity is both intensified and transformed into broader diagnostic and normative gestures, culminating in the compressed late cluster where publication intention, polemical urgency, and retrospective self-accounting collide. Throughout, the Nachlass volumes, governed by chronological editorial principles, remain as a constant counter-force: they display the workshop of thought as such, including plans, lists, outlines, and the layered temporality of notebooks, thereby maintaining the openness of Nietzsche’s project against every interpretive impulse to finalize it

Table of Contents:

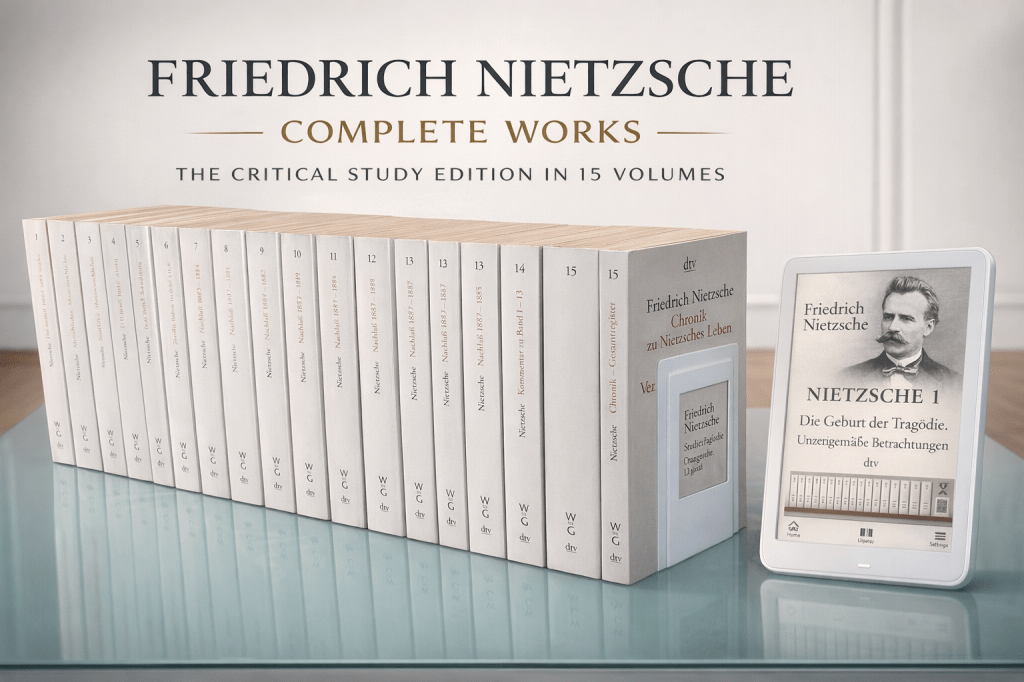

Critical Study Edition of Friedrich Nietzsche, De Gruyter, 1988 (2nd revised edition)

- Vol. 1 (Complete Works: Critical Study Edition): The Birth of Tragedy; Untimely Meditations I–IV; Posthumous Writings (1870–1873)

- Vol. 2: Human, All Too Human I & II

- Vol. 3: Daybreak; Idylls from Messina; The Gay Science

- Vol. 4: Thus Spoke Zarathustra

- Vol. 5: Beyond Good and Evil; On the Genealogy of Morality

- Vol. 6: The Case of Wagner; Twilight of the Idols; The Antichrist / Ecce Homo; Dionysian-Dithyrambs / Nietzsche contra Wagner

- Vol. 7: Posthumous Fragments (1869–1874)

- Vol. 8: Posthumous Fragments (1875–1879)

- Vol. 9: Posthumous Fragments (1880–1882)

- Vol. 10: Posthumous Fragments (1882–1884)

Vol. 11: Posthumous Fragments (1884–1885)- Vol. 12: Posthumous Fragments (1885–1887)

- Vol. 13: Posthumous Fragments (1887–1889)

Vol. 14: Introduction to the Critical Study Edition; Catalogue of Works and Sigla; Commentary on Volumes 1–13Vol. 15: Chronicle of Nietzsche’s Life; Concordance; Complete Index of Poems; General Index

Leave a comment