Einstein’s The Meaning of Relativity secures a distinctive place in the literature because it compresses a complete conceptual itinerary—from classical kinematics to the relativistic unification of gravitation and geometry—into a set of lectures whose unity of method is continuously tested and amended across successive editions. The book’s scholarly stake is double: first, it re-derives the basic invariants and transformations of special relativity directly from operational definitions of measurement and simultaneity; second, it reconstructs general relativity from an explicit calculus of tensors and variational principles, leading to a cosmological appendix and, in later editions, to a generalized, non-symmetric field theory whose equations are judged by a philosophical metric of strength (the reduction of free data) rather than mere formal ingenuity. Across this arc the work stages persistent tensions—between measurement and geometry, invariance and covariance, locality and global structure—so that what begins as a survey of first principles culminates in a reappraisal of the very criteria by which field equations count as physically meaningful.

Einstein opens by binding the theory of relativity to a preliminary analysis of how concepts of space and time arise from the coordination of experiences, insisting that scientific concepts purchase their legitimacy solely by their service in representing experience. This is a methodological maxim rather than a psychological thesis. It enables him to define clocks and rigid bodies as systems with special counting properties and to insist that only those perceptions common to different observers achieve the impersonality physics requires. Spatial talk is then anchored to bodies of reference, not to an abstract “space in general,” and the Euclidean structure appears as a special codification of congruence relations for rigid intervals whose metric form  singles out Cartesian coordinates by the orthogonal transformations that preserve it. From the start, invariants rule: distance, volume (with Jacobian determinant ±1), and the transformation-behavior of vectors and tensors are derived as the only coordinate-free content of the geometry that pre-relativistic physics quietly presupposed. The result is a toolbox—linearity, orthogonality, contraction, symmetry and skew-symmetry—that allows laws to be written in forms whose form is preserved under the transformations that express isotropy and homogeneity.

singles out Cartesian coordinates by the orthogonal transformations that preserve it. From the start, invariants rule: distance, volume (with Jacobian determinant ±1), and the transformation-behavior of vectors and tensors are derived as the only coordinate-free content of the geometry that pre-relativistic physics quietly presupposed. The result is a toolbox—linearity, orthogonality, contraction, symmetry and skew-symmetry—that allows laws to be written in forms whose form is preserved under the transformations that express isotropy and homogeneity.

This deeply operational stance immediately translates into physics. Newtonian particle mechanics appears as a vector equation  whose sense is secured by the tensor character of each term and whose consequences (kinetic energy, the virial, the moment equations) are displayed as invariant statements under spatial rotations. Stress in a viscous fluid is written as a symmetric rank-2 tensor built from linear combinations of velocity gradients constrained by isotropy. And the Maxwell-Lorentz equations are reorganized so that what appears as a magnetic “vector” in three dimensions transforms more naturally as a skew-symmetric rank-2 tensor, with the familiar curl/divergence structure compactly expressed as tensor divergences and cyclic sums. The entire preface to relativity, then, already looks like relativity in embryo: physics is a calculus of invariants over bodies of reference.

whose sense is secured by the tensor character of each term and whose consequences (kinetic energy, the virial, the moment equations) are displayed as invariant statements under spatial rotations. Stress in a viscous fluid is written as a symmetric rank-2 tensor built from linear combinations of velocity gradients constrained by isotropy. And the Maxwell-Lorentz equations are reorganized so that what appears as a magnetic “vector” in three dimensions transforms more naturally as a skew-symmetric rank-2 tensor, with the familiar curl/divergence structure compactly expressed as tensor divergences and cyclic sums. The entire preface to relativity, then, already looks like relativity in embryo: physics is a calculus of invariants over bodies of reference.

With this grammar in hand, Einstein reposes the central question: can there be a relativity with respect to the state of motion of the reference body, i.e., an equivalence among some class of moving frames? Classical mechanics tacitly answers yes for uniform translations, but it does so using two hidden assumptions about scales and clocks—absolute length and absolute time—that cannot survive contact with electrodynamics. He recounts the Galilean transformation as the formal codification of those assumptions, with the comforting consequences that Newtonian equations remain covariant. But once Maxwell-Lorentz laws are taken as the guide, the Galilean scheme fails: the velocity of light becomes direction-dependent in a moving frame, implying a privileged ether frame, which experiment does not reveal. The Michelson–Morley null results, along with aberration, Fizeau’s measurements in moving media, and de Sitter’s double-star arguments, secure the empirical footing for a new relativity principle joined to the constancy of the vacuum light speed.

Einstein’s well-known move is to bring time under the same operational discipline as space. He specifies a procedure for synchronizing clocks distributed over a rigid lattice by light signals, fixing the time at one location by appeal to a signal’s emission time and travel time as computed with a universal c. He defends this step explicitly: any physically significant time concept must be mediated by processes that establish cross-place relations; light propagation is singled out only because it is best-understood. Here the point is not to deify optics but to warrant the structure of simultaneity by a process whose lawlike behavior is already secured. The upshot is that simultaneity, and hence “time,” is system-relative; the very idea of absolute time never emerges from the operational scheme.

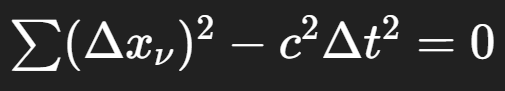

From two axioms—the relativity principle for inertial frames and the constancy of light speed—Einstein derives the Lorentz transformation. He compresses the deduction to a single invariant statement: for a light signal connecting two events, the quadratic form  must be preserved in all inertial frames, a condition that yields a family of linear transformations on space and time which, in Minkowski’s language, act as generalized rotations in a four-dimensional manifold once the imaginary time x4 = i ct is introduced. The Lorentz group is here the true symmetry of inertial physics: it is the metric-preserving group for a quadratic form with opposite sign on the temporal term, and its special case in which only x1 and x4 mix corresponds to relative motion with speed v. In Einstein’s hands the famous kinematic effects follow not as curiosities, but as operational entailments: moving rods are Lorentz-contracted along the motion, and moving clocks are dilated, each effect uncovered by reading off how synchronized coordinates are transformed and by insisting that no extraneous scale factor λ(v) be smuggled into the relations. The prohibition of such a factor is argued by a careful cylinder thought-experiment that uses spatial isotropy and the composition of boosts to show that λ must equal unity.

must be preserved in all inertial frames, a condition that yields a family of linear transformations on space and time which, in Minkowski’s language, act as generalized rotations in a four-dimensional manifold once the imaginary time x4 = i ct is introduced. The Lorentz group is here the true symmetry of inertial physics: it is the metric-preserving group for a quadratic form with opposite sign on the temporal term, and its special case in which only x1 and x4 mix corresponds to relative motion with speed v. In Einstein’s hands the famous kinematic effects follow not as curiosities, but as operational entailments: moving rods are Lorentz-contracted along the motion, and moving clocks are dilated, each effect uncovered by reading off how synchronized coordinates are transformed and by insisting that no extraneous scale factor λ(v) be smuggled into the relations. The prohibition of such a factor is argued by a careful cylinder thought-experiment that uses spatial isotropy and the composition of boosts to show that λ must equal unity.

Tension is staged carefully here: the geometry of measurement has been rebuilt on invariant quadratic forms in which time is geometrically unlike space, yet the calculus of four-vectors and tensors regains a unity of treatment. The basic invariant ![]() (with x4=ict) is not merely a fancy notation but the proper scalar that classifies separations as lightlike, timelike, or spacelike and thereby encodes the causal articulation of events by light cones. These structures—which have no counterpart in Euclidean geometry because s2 need not be positive—are the internal backbone of dynamics: four-vectors transform as the coordinate differences do; rank-2 tensors follow bilinear rules; and the invariant calculus enables the re-expression of electromagnetic fields and energy–momentum in compact, frame-independent form. This is why, in Einstein’s exposition, the “content” of special relativity is never the counterintuitive kinematics alone; it is the enforcement of a new invariance structure that requires all bills—mechanical, electromagnetic, thermodynamic—to be paid in tensors.

(with x4=ict) is not merely a fancy notation but the proper scalar that classifies separations as lightlike, timelike, or spacelike and thereby encodes the causal articulation of events by light cones. These structures—which have no counterpart in Euclidean geometry because s2 need not be positive—are the internal backbone of dynamics: four-vectors transform as the coordinate differences do; rank-2 tensors follow bilinear rules; and the invariant calculus enables the re-expression of electromagnetic fields and energy–momentum in compact, frame-independent form. This is why, in Einstein’s exposition, the “content” of special relativity is never the counterintuitive kinematics alone; it is the enforcement of a new invariance structure that requires all bills—mechanical, electromagnetic, thermodynamic—to be paid in tensors.

The passage to gravitation is announced as both a conceptual deepening and a methodological extension. The equivalence principle—stated in the register of inertia—says that freely falling motion erases gravitational effects locally, so that in small domains one recovers inertial lawfulness. This suggests that what appears as gravitational force globally is expressible as the failure of the metric to admit a global Euclidean (and special-relativistic) coordinatization. Einstein leverages the earlier invariant calculus into the Riemannian setting: one replaces partial derivatives by covariant ones, introduces the connection coefficients Γ to define parallel transport and geodesy, and forms curvature tensors Rμν and the scalar R by contraction. The free motion of a particle, inertial in the special theory, is now the geodesic equation ![]() ; in coordinates adapted to an inertial frame, the Γ vanish and the equation reduces to straight lines, just as required. The construction is both conservative and revolutionary: conservative, because it is an extension of the Euclidean-to-tensor logic; revolutionary, because the metrical coefficients acquire physical content, with curvature replacing force as the source of inertial deviation.

; in coordinates adapted to an inertial frame, the Γ vanish and the equation reduces to straight lines, just as required. The construction is both conservative and revolutionary: conservative, because it is an extension of the Euclidean-to-tensor logic; revolutionary, because the metrical coefficients acquire physical content, with curvature replacing force as the source of inertial deviation.

At the level of laws, Einstein’s general theory expresses gravitational dynamics by field equations that relate geometry and matter via a symmetric energy–momentum tensor. In these lectures, the stress is less on the popular incantation “geometry tells matter how to move…” than on the disciplined fact that the relevant quantities (metric, connection, curvature, energy–momentum) are tensors or derived invariantly, so that their equations admit any coordinate system as admissible provided one writes them in the covariant form that encodes the equivalence of all frames. The reader sees why Einstein earlier policed the use of invariants so jealously: once “the law = tensor identity” is adopted as the watchword, the coordinate smoothness of the general theory is not a mystique but a consequence. The physical content returns as calculable predictions in appropriate weak-field limits, including the perihelion advance and deflection of light, but in the Princeton text the emphasis is consistently on the chain of reasoning that authorizes those predictions rather than on cataloguing them.

The outer framing of the book matters. These pages stem from the 1921 Stafford Little Lectures at Princeton, later augmented in successive editions: first an appendix on advances since 1921; then a second appendix on a generalized theory of gravitation; and, in the sixth edition, a revised Appendix II in which the generalized theory is reformulated to simplify derivations and present field equations in a clearer, more transparent shape. The sixth edition note states this explicitly and dates the revision to December 1954, underscoring that the slender “little book” is also a laboratory in which Einstein continues testing criteria for acceptable field theories, well past the consolidation of general relativity proper. The architecture thus makes the lectures a living vessel into which new methodological scruples—about symmetry, invariance under transposition, and, crucially, the strength of a system of equations—are poured and stirred.

Appendix I, on the cosmological problem, is a model of how Einstein strives to connect the formalism to global structure without sacrificing the criterion of observational discipline that opened the book. He considers the large-scale character of space, the possibility of spherical spatial sections, and the relation between average mass density and spatial curvature, sketching how one could bound the ratio of dark to luminous matter by using the observed kinematics of globular clusters to estimate the mass required to generate their gravitational field. The inferential shape of this argument is delicate: cluster dynamics yield lower bounds on the ratio of non-radiating to radiating matter; if the inferred mean density exceeds a certain threshold, spherical character follows; and one must respect external chronological constraints such as the radiometric ages of the Earth’s crust. He insists that a contradiction with reliable age determinations would disprove the cosmological scheme, and he admits that no trustworthy upper bound for the average density is presently available. The cosmological appendix therefore exhibits the same honesty as the opening methodological chapter: concepts gain legitimacy insofar as they regulate experience, but the regulation includes principled deference to independent empirical anchors.

If Appendix I exemplifies how global questions are made tractable by measured modesty, Appendix II displays Einstein’s most ambitious and reflective attempt, years later, to generalize the field concept beyond the symmetric metric theory. The first move is not a new equation but a meta-criterion: one must assess a system of field equations by its strength, which Einstein defines as the degree to which the equations reduce the free data required to determine a field. This criterion is operationalized by counting the number of free coefficients order-by-order in Taylor expansions at a point, subtracting the constraints imposed by the field equations and any identities among them, and thus obtaining an asymptotic measure of how “strong” a system is in eliminating arbitrariness. In clear examples—the scalar wave equation, symmetric gravitational fields, and ultimately the non-symmetric field—the procedure shows how to compare theories with different numbers and kinds of field variables. The point is methodological: a good theory is not merely elegant; it leaves little latitude for arbitrary initial data while remaining compatible and integrable.

Within that framework Einstein introduces a non-symmetric field characterized by an asymmetric fundamental tensor and a connection whose transposition properties matter. A core postulate is transposition invariance: the field equations should remain invariant when certain index exchanges are performed, a physical desideratum meant to encode the symmetrical entrance of positive and negative electricity into the laws. The difficulty is that the natural contracted curvature Rik is not transposition symmetric; its transposition differs by terms with derivatives and products of the connection. To repair this, Einstein defines a pseudo-tensor U1ik built from the connection by a linear combination that ensures the contracted curvature expressed in terms of U becomes transposition symmetric. This U-formalism introduces a new gauge-like freedom, the λ-transformation, under which U shifts by derivatives of an arbitrary vector field; crucially, the transposition-symmetric expression built from U remains invariant under these transformations. As a result, the field variables possess an internal redundancy whose careful handling is essential both for the form of the equations and for the correct counting in the later strength comparison.

The calculus continues: Einstein rewrites the transformation laws, exhibits the invariants available in the non-symmetric context, and constructs a variational principle whose Euler–Lagrange equations are transposition invariant once the λ-invariance is appropriately normalized. The philosophical nerve of this appendix is that Einstein refuses to select equations solely for their symmetry pedigree; he asks whether the system, as amended by identities and gauge freedoms, is strong. By the enumeration procedure, the asymptotic count for the non-symmetric field gives a coefficient z1=42, markedly weaker than the pure gravitational field’s z1=12. He also analyzes a tempting alternative that enforces transposition invariance directly at the level of the action without U; the result has no λ-invariance and is even weaker z1=48, hence to be rejected. The conclusion is not triumphalist—no final unification is claimed—but it is methodologically clarifying: symmetry constraints must be balanced by a measure of determinative power; otherwise one risks “pretty equations” that underdetermine the world.

If one steps back across the whole composition, a coherent sequence appears. The lectures begin by submitting the geometrical language of physics to an invariantist audit: only those objects and relations whose transformation properties are well-behaved deserve to count as contentful. They proceed to re-ground simultaneity, time measurement, and velocity composition with an operational clarity that makes the Lorentz transformation a necessity rather than an option; the kinematic corollaries fall out as readings from synchronized grids rather than metaphysical puzzles. They then generalize the invariant calculus to Riemannian geometry, where the connection and curvature are not metaphors but the generative apparatus of motion, geodesy, and field law; the equivalence principle serves as the physical warrant for replacing “forces” by connection coefficients, while conservation statements migrate into covariant divergences of energy–momentum. Finally, the appendices show two extensions of the same logic: a cosmological “census” in which density, curvature, and observational chronology constrain global geometry without speculation outrunning warrants; and a non-symmetric field theory in which symmetry desiderata, gauge freedoms, and the strength of equations are made to stand trial before the same invariance court that presided in the opening chapter. The book thus coils back upon its origin: measurement and invariance have always been its center of gravity.

Along this path, conceptual tensions are not smoothed away; they are staged and then folded into the method. There is the tension between coordinate freedom and empirical definiteness, which Einstein resolves by insisting that the only physically meaningful claims are those that can be rendered as invariants (scalars), vector/tensor equalities, or covariant equations whose content survives any admissible re-labeling of events and frames. There is the tension between local inertiality and global curvature: one cannot erase gravity everywhere, only in the infinitesimal; the price of general covariance is that only local coincidences are immune to artifacts, while global statements require integrals of curvature or boundary conditions. There is the tension between symmetry and determination: symmetries multiply admissible representations, so one must accompany them with an account of gauge—to prevent counting illusions—and with a criterion that tracks how many arbitrary functions remain after equations and identities have done their work. And there is the final tension between geometry and physics itself: is geometry merely a re-description of force, or is it the very substance of gravitational dynamics? Einstein’s procedure answers by example rather than by manifesto: the geodesic equation is derived as the condition of parallel transport extremizing the line element, and the field equations are built by variational means out of the metric and curvature; if there is a remainder of “force,” it is disposed of locally by free fall and globally by curvature tensors.

One can also track how earlier parts of the book are displaced by later ones without being discarded. The Euclidean invariant ![]() that anchored pre-relativity measurement is retained as a special case of the Minkowski s2 and then superseded by the Riemannian line element

that anchored pre-relativity measurement is retained as a special case of the Minkowski s2 and then superseded by the Riemannian line element ![]() , which itself becomes the object of dynamics once matter and curvature are coupled. The electromagnetic field, introduced in three-space as a skew-symmetric tensor, finds its natural four-tensor form in the special theory, and in the generalized appendix it inspires the hunt for transposition-symmetric structures that could host both gravity and electromagnetism. Even the synchronization convention of special relativity returns as a local shadow of the much richer problem of choosing coordinates in curved spacetime; within any local inertial frame, Einstein’s definition by light signals regains its primacy, while globally one must navigate affine connections and curvature. And the proofs about fluid stresses, virial relations, and conservation laws reappear in covariant clothing when energy–momentum conservation is expressed as the vanishing covariant divergence of the stress–energy tensor rather than as a divergence-free three-vector flux. The earlier material is not refuted by the later; it is reinterpreted within successively more general invariance structures that demand their own notions of measurability.

, which itself becomes the object of dynamics once matter and curvature are coupled. The electromagnetic field, introduced in three-space as a skew-symmetric tensor, finds its natural four-tensor form in the special theory, and in the generalized appendix it inspires the hunt for transposition-symmetric structures that could host both gravity and electromagnetism. Even the synchronization convention of special relativity returns as a local shadow of the much richer problem of choosing coordinates in curved spacetime; within any local inertial frame, Einstein’s definition by light signals regains its primacy, while globally one must navigate affine connections and curvature. And the proofs about fluid stresses, virial relations, and conservation laws reappear in covariant clothing when energy–momentum conservation is expressed as the vanishing covariant divergence of the stress–energy tensor rather than as a divergence-free three-vector flux. The earlier material is not refuted by the later; it is reinterpreted within successively more general invariance structures that demand their own notions of measurability.

A final word on tone and discipline. Throughout, Einstein restrains quotation, rhetorical flourish, and historical asides in favor of explicit constructions. When he acknowledges criticisms—e.g., that relativity smuggles in optics by founding time on light—he answers by tightening the operational chain: time must be defined by inter-place processes; light is chosen because it is the best-controlled process available. When he reaches cosmology, he will not tolerate a scheme that contradicts reliable geochronology; when he attempts unification, he refuses to baptize a system that is too weak in the precise sense of leaving too many free coefficients or that loses a critical invariance such as λ-freedom. The philosophical register is therefore exacting rather than speculative: a field theory deserves assent only to the extent that its equations are covariant under the physically warranted transformation-group, reduce the arbitrariness of initial data, and respect the operational meaning of the quantities they relate. This maxim, present in the book’s opening meditation on the “origin of our ideas of space and time,” continues to adjudicate every later construction, from Lorentz kinematics to geodesic motion, from cosmological averages to the non-symmetric field.

Clarifying, then: The Meaning of Relativity is not merely a sustained demonstration that physics advances when one binds measurement to invariance, law to covariance, and proposal to strength. The work’s distinctive contribution is to make this demonstration in three movements—the kinematics of light and simultaneity, the dynamics of geodesy and curvature, and the meta-dynamics of field-equation assessment—each of which both consumes and redeploys the previous movement’s results. What begins as the disciplined reinterpretation of timekeeping becomes a general method for writing laws; what consolidates as the Riemannian rendering of gravitation becomes a template for judging generalized theories; and what appears as a cosmological aside becomes an object lesson in how global claims are earned: by estimates, lower bounds, and scruple before independent data. The book is therefore best read as a single argument with appendical codas—an argument whose conclusion is less a theorem than a standard: theories must speak the language of invariants, submit to empirical anchoring, and earn their place by the strength with which they determine the world.

Leave a comment