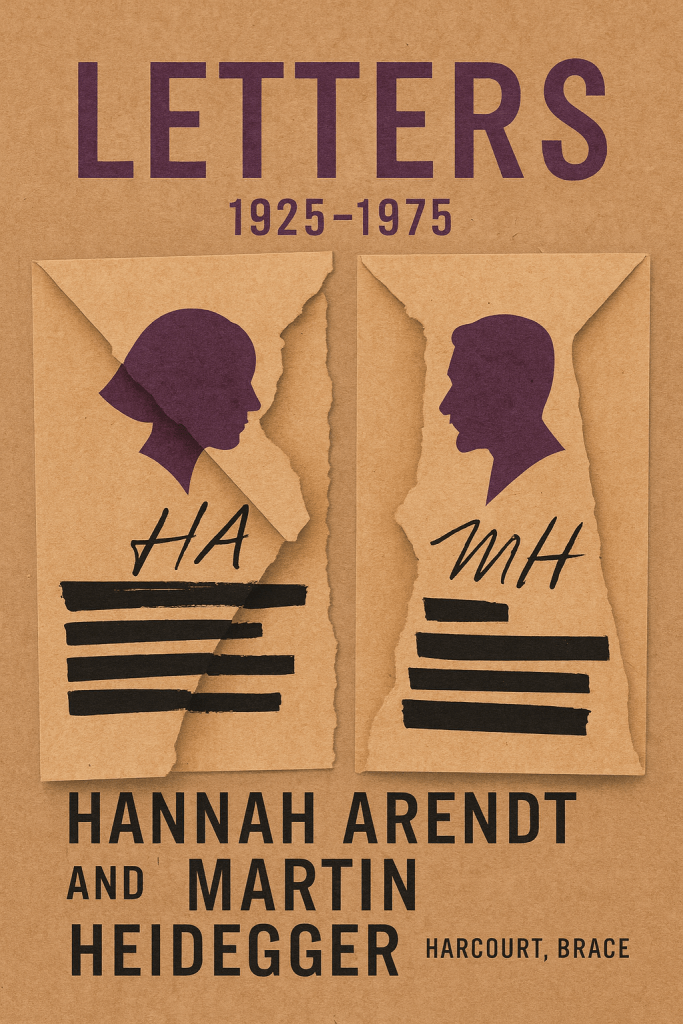

The volume that gathers the correspondence between Hannah Arendt and Martin Heidegger from 1925 to 1975 is not simply a compendium of private sentiments made public, but an exacting, often disquieting dossier of the twentieth century’s conceptual crises refracted through the most intimate medium two thinkers share: a practice of writing that tests the limits of what can be said, what can be withheld, and what must be remembered. The book’s editorial frame already unsettles any expectation of transparency or closure. Edited by Ursula Ludz and translated by Andrew Shields, the collection is anchored by a foreword that refuses to romanticize the archive even as it acknowledges the fascination it exerts; what survives is uneven, fragmentary, and asymmetrical—119 pieces from Heidegger to Arendt, only 33 from Arendt to Heidegger—and the disproportion itself becomes a datum for thought, not a mere accident of preservation. The result is a correspondence whose lacunae function like apertures through which history and philosophy, guilt and judgment, eros and rigor, repeatedly enter and strain the tissue of the letters themselves.

The physical and bibliographical clarity of the English edition—Harcourt’s first U.S. edition, with its Dante type, a precise apparatus of notes, and appendices that include poems, a prose manuscript of Arendt’s from 1925, and ancillary pieces—conceals a methodological wager: to publish nearly “unedited” texts, intervening only where legibility and minimal normalization require it, and to leave interpretive labor to future readers who must accept that what matters most here is less a continuous narrative than a series of intensities separated by long stillnesses. Even the table of contents—At First Sight, The Second Look, Autumn—is less a chronology than a phenomenology of encounter, return, and ripeness, transforming editorial headings into a schema of the moods in which thinking withstands or fails the events that claim it. The promise is that the life archived here is not the raw material for psychology; it is an index of what each writer, in different idioms, calls a path—Weg, vita activa, vita contemplativa—that only shows itself in retrospect and only as a tangled synthesis of biographical fact, philosophical experiment, and historical pressure.

From the outset, the correspondence situates itself as a scene of instruction that instantly overflows pedagogy. The opening note from February 10, 1925, is a compressed ethics of approach and distance—a professor who “must come see you” meets a student whose presence has already unsettled the academic frame, and the text decides, almost ceremonially, that the student–teacher relation is merely the “occasion” for something that demands a purer register. The subsequent lines—about simplicity, clarity, purity, worthiness, the impossibility of possession, and a “loyalty” that is to help the other remain true to herself—recast eros as a discipline of restraint rather than a disclosure of secrets. It is typical of the letters that a boundary is installed precisely where it seems to be breached; that a kiss is imagined not as consummation but as a vow to bear the “honor” of the other’s being into one’s work; that pedagogy confesses its inadequacy at the moment it dares to protect the fragile emergence of what the letter calls a “purest feminine essence.” What to do with such language—its gendered hierarchies and its tender solicitude? The book does not defend it; it exhibits it, as a material the reader is obliged to interpret as part of the concrete syntax of a time, a place, and a pair of lives that would, within eight years, be torn apart by the political catastrophe whose consequences noiselessly saturate every later page.

The early exchange cannot be read apart from its simultaneity with the Marburg years in which Being and Time is written and discussed, and yet it would be an error to reduce the private registers to footnotes for a public treatise. The letters insist on a different scene of formation: brief walks in rain, mountain solitude at Todtnauberg, a student’s silent presence that is said to lend nobility to “free intellectual life,” the florid evocations of spring and lilac that are hardly decoration but a rhetorical labor to make the non-philosophical appear foundational to philosophizing. Heidegger’s descriptions of snow fields, chopping wood, the rhythms of a high-valley day are not pastoral indulgences; they are deployed as an argument that the life of elemental proximity—storm, sky, slope—loosens the grip of analytic habits and readies thought for its questions. Even here, in a tone whose vocabulary is domestic and seasonal, the letters aim at nothing less than the problem of how a human being sustains the conditions that let questioning become work, work become path, path become destiny. When he writes that the “demonic” struck him, and that this force is transfigured by the beloved’s “shining brow” and “beloved hands,” the hyperbole should be heard as a labored figure for the very Geworfenheit that Being and Time will thematize—except that, in letters, thrownness is not a neutral existentiale; it is redeemed or damned in the address to a singular you.

No less weighty on the other side is Arendt’s prose manuscript from April 1925, Shadows, which the edition publishes in full. If the early Heideggerian letters work to assure the student that a path exists and can be guarded by a love that refuses to possess, Arendt’s text dramatizes a psyche in which tenderness and strangeness have fused so tightly that worldliness itself risks falling under the aspect of a fear indistinguishable from longing. The piece has the structure of a self-diagnosis that refuses cure: the “dichotomizing” of life into Here and Now versus Then and There, the displacement of banality by a readiness to find the odd in the ordinary, the way the double nature of existence—agitation and self-absorption—binds the writer to herself even as it obstructs access to herself. The culminating image of a “deadly fear of being sheltered” coupled with an expectation of callousness turns shelter itself into threat, and the text dares to say that there is a suffering one must be grateful for because only such suffering makes anything at all worthwhile. Whatever else Shadows is, it models the peculiar clarity Arendt will later call judgment’s work: to see through the pathologies of a time not by idealization but by a conscious refusal to be reconciled to them. If Heidegger’s letters domesticate eros into vigil and discipline, Arendt’s manuscript insists that the psychic economy of longing can collapse into fear, that the very capacity to be moved can harden into a gaze that turns everything into nothing. The two registers do not cancel each other; they exhibit the tension that will mark their philosophical difference thereafter.

The first phase closes not through fatigue, but through history’s assault. The foreword reconstructs, from a letter of the winter of 1932–33, an exchange in which Arendt confronted Heidegger with talk of antisemitism and in which he responded with a defense that the editor judges unsatisfying—and that, in any case, stands on the threshold of his rectorship and the notorious address whose afterlives would shadow every possibility of rapprochement. At precisely this juncture the archive grows nearly silent, and the silence is not merely a biographical fact: Arendt, a Jew, flees Germany in 1933, first to Paris and then to New York; Heidegger’s career enters its period of political compromise and post-war sanction. The correspondence, suspended for nearly two decades, is thus framed by two antithetical movements—exile and provincial withdrawal—each of which becomes, for each writer, a condition for the development of work that cannot be extricated from the wound that occasions it. That abyss produces not explanation but what the letters later call a “second look.”

When contact resumes in February 1950, the rhetoric has changed, but not its ethical claim. The motif of Wiederkehr—return with reckoning—enters, and the language of spring gives way to a music of late winter. She writes from Freiburg in the days when his ban on teaching is lifting; he writes of “paths of thinking” under pressure and the clamorous public controversies of the early Federal Republic; yet each letter strives to discover a mode in which the past is neither denied nor administered but held as a form of lucidity. The correspondence speaks—now explicitly—of a “conversation about language,” recalled on paths by birches and re-remembered even in 1965 as a scene decisive for both. The recurrence of that phrase is not nostalgia; it is the quiet formulation of a pact that understanding must not be confused with absolution, and that judgment, for Arendt, requires the difficult composure that refuses both forgetting and resentment. It is crucial that, in this very period, she reports on work that will crystallize as The Human Condition, while he returns to thematic trajectories that will culminate in the lectures and essays of the fifties. The letters—reserved, occasionally tense, often meticulously courteous—testify to a situation in which the political cannot be dissolved into the personal without violence, and in which the personal cannot be purified of the political without bad faith. The achievement here is not reconciliation in the sentimental sense, but a renewal of conversation in which each writer consents to the other’s persistence as a problem and a gift.

Between 1955 and 1965 the archive thins to near-invisibility. The editor discreetly sketches reasons without dramatization: Arendt’s complicated, sometimes sharp judgments of Elfride Heidegger visible in private correspondence with others; the strained triangle with Karl Jaspers; a sense that both major writers were absorbed, in those years, by work they suspected the other might not wholly approve. If the silence rankles, the volume declines to fill it with speculation. What matters is that the third phase—Autumn—begins in 1966 with an exchange that names the season both literally and as a figure of ripeness, sobriety, fatigue, and a new clarity about ends. He writes for her sixtieth birthday; she replies with a sentence as severe as it is consoling: those whose hearts were broken by spring can have them made whole again by autumn. Suddenly the correspondence expands into a balance it lacked before—a dialogue of equals, by now armored against scandal and chastened by mortality. There is reconciliation here, but it is reserved, almost liturgical, drawing Elfride more steadily into acknowledgment even on Arendt’s side, and converting earlier pathos into what both now call Stille, a stillness that is not refusal but a change in the demands each places on the other.

The late letters are thick with goals of closure. He speaks of the labor to think into a more exact shape; she entertains the hope of a second volume to the Vita Activa project—the book we know as The Life of the Mind—and asks permission to dedicate it to him should it come to completion. It is characteristic of the exchange that public and private celebrations interpenetrate the philosophical tasks: the year of his eightieth birthday becomes a scene of gratitude in which she delivers her radio essay, “Martin Heidegger is eighty years old,” later printed in Merkur, and addresses him with an inscription that remembers “forty-five years” in a gesture that is neither confessional nor polemical but intensely sober. The letters note her visits to Freiburg in the wake of Jaspers’s death and again after she is widowed, and they record his dedications—Kant’s book in its expanded 1973 edition, and the printed eulogy for Hildegard Feick—in an economy of brevity that condenses acknowledgment to a signature: “For Hannah—Martin.” Two final dates silently bind the archive: the last letter, with an invitation for a visit, on July 30, 1975; the last meeting in Freiburg on August 12 of that year; her sudden death in December; his in May 1976. The facts are clinical; the effect, in context, is liturgical, announcing an end that the letters had been preparing themselves to endure.

The editorial foreword is not merely a preface; it is an argument that to publish such documents is to withstand two symmetrical temptations: first, to turn the private into spectacle and thereby to preempt understanding with titillation; second, to suppress the private in the name of dignity and thereby to feed rumor and banal fantasy. The path the edition chooses—motivated in part by the circulation of a controversial book that isolated the affair from the intellectual labor of both protagonists—is to release everything available, to admit the incompleteness of the corpus, and to trust that scholars who attend to the texture of writing will draw conclusions that are careful, limited, and revisable. Even the polemical point—that sensationalism thrives in secrecy—is made without rancor; the volume’s wager is that documented reality, however partial, interrupts invention. In this sense, the book does not compete with biography; it interrupts it, marking thresholds beyond which interpretation becomes conjecture.

The asymmetry of the surviving letters is more than a material inconvenience. It discloses—painfully—the gendered economy of literary survival, the accident of who keeps what, and the contingency by which drafts and carbons outlast originals. The foreword is lucid about the limits: a quarter or less of the extant material is by Arendt; much of it survives as drafts whose dispatch cannot be confirmed; later letters are typewritten carbons as often as originals. Against that attenuation, the editor sets an almost detective confidence that the Heidegger Nachlass has been combed and that what can be gathered is here. In this space of partial voices, Arendt’s decision to preserve what she preserved, even allegedly against an agreement to destroy, becomes a theoretical act in its own right: a refusal to let forgetting masquerade as tact, a commitment to memory as the minimal condition for judgment. The detail that she kept the poems and letters in a desk drawer in her bedroom has the force of a thesis: that the secret does not preclude publication but delays it, dissociating time for living from time for reading.

At the level of style, the correspondence is a school of reserve. The foreword registers a period “modesty” that will feel foreign to readers formed after the sexual revolution, but it is careful to identify the moral risk internal to reserve: there is a “guilt that comes from reserve,” and there are moments in which both correspondents confess that they sometimes talk too much and at other times too little. Between these poles, the letters achieve an “elevated” diction that can appear evasive yet often condenses more honesty than unedited candor can bear. The letters’ beauty, where it occurs, is not decoration; it is an instrument for permitting speech at all under conditions in which direct statement would distort or destroy. Reading them is therefore not voyeurism but a drill in an ethics of reception: to withhold greedy inference, to resist polemical harvest, to attend to what is not explained because explanation would betray it.

One can observe, in the earliest letters, a decisive labor to separate a philosophical scope from sentimental privacy without reducing one to the other. The Marburg notes insist again and again that the student’s presence—her quiet in Husserl’s evenings, her unspectacular attendance at a bench after a concert, even her way of entering an office, hat low over large, quiet eyes—has the dignity of what permits thinking to remain thinking rather than publicity. To say this is not to sanctify the asymmetry of roles; it is to admit that what the letters seek to secure is a non-instrumental intimacy in which no public victory can be won and no private exploitation permitted. If this is an idealism, it is an idealism the later decades will test without, however, invalidating it. The 1950s letters, when they are not harried by external controversy and inward worry, return to a motif: a “conversation about language” on a path near birches. The modesty of the scene—unexceptional in detail—becomes the figure for a confidence both demand of the other: that thinking is possible again by walking and talking; that the failure of one epoch to hold an ethos does not abolish the need to keep speaking.

The book’s apparatus makes explicit that what we are reading is set within an archive designed to be useful. The notes are sparing but careful; they assume readers who know the vocabularies of both bodies of work and who can track references without hand-holding. The editors standardize only what must be standardized and italicize what the writers marked, thereby conserving emphasis without insinuating commentary. Lists of works by both authors and of abbreviated literature form a navigational mesh that positions the letters within the broader expository corpus. Even the decision to divide the letters into three titled sections—At First Sight, The Second Look, Autumn—is an interpretive help that stops short of exegesis, gesturing to periods without overdetermining them. The book is, in this sense, not only a text one reads but a device one uses to cross-reference commentaries, lectures, essays, and the secondary literature that is itself entangled with the history of this relationship.

Consider three motifs that, across decades, do not so much develop as return in altered keys. First, the impulse to convert love into a promise not of possession but of guardianship. Early phrases about being unable to “call you mine,” about belonging in the other’s life without claiming her, are not gallant flourishes; they are reductions, in the Euclidean sense, to the axioms of a practice in which Eros is a renunciation of appropriation that seeks to keep open the other’s path to herself. The idea recurs in the Augustinian citation of amo: volo ut sis—I love you; I want you to be what you are—not as a slogan but as a measure against which one’s own conduct will repeatedly fail. If this formulation scandalizes a contemporary expectation that intimacy must be confessed, the letters use the scandal to teach that confession, when it is not yet judgment, can weaponize exposure and that there is a shame in speaking that reserve alone can forestall.

Second, the thematic of language, not as stylistic ornament but as milieu. The letters remember walks in which “conversation about language” took place; they entangle this memory with recurrent efforts, on both sides, to find words for experiences that either disintegrate into cliché or harden into proclamation. The late correspondence’s invocation of Stillness—a stillness that is neither mute nor merely quiet—names not silence but a disciplined diminishment of need, so that language can bear, with fewer distortions, what the writers are now prepared to say and what they are now prepared to leave unsaid. This is not quietism; it is a learned refusal to make language carry contraband—resentment, self-exculpation, moral grandstanding—that would falsify the address. The very grammar of the letters—so often desiring to tell, so often withdrawing into allusion—exhibits that effort without concluding it.

Third, the politics that the book neither brackets nor explicates. The editor’s reconstruction makes it impossible to ignore that the catastrophic divergence of 1933 produces the vacuum in which the archive vanishes for two decades, and the later letters refuse to behave as if the past could be repaired by eloquence. There is no apologia here; there is endurance. Arendt’s capacity to resume conversation is not a denial of judgment; it’s a practice of judgment that declines the absolutism both of condemnation without remainder and of forgiveness without cost. Heidegger’s letters, for their part, do not settle the matter of responsibility; they document a man who, in public embattlement and private withdrawal, struggles to think under conditions he helped to worsen. The correspondence is thus a record of a charged asymmetry: the voice that suffered and fled meets the voice whose compromises became scandal, and the exchange dares to continue without the false equilibrium of erasing difference. This risk—refusing both the closure of denunciation and the anesthetic of oblivion—defines the ethical difficulty that gives the book its gravity.

The volume’s appendices are not padding; they are integral to the book’s dialectic between life and work. Heidegger’s poems from 1950 and 1951—of which Arendt, in proud exaggeration to a friend, could say she had occasioned a small enrichment of the German language—grant access to affects otherwise concealed by his prose’s reticence. Arendt’s early poems (1923–1926) and the prose of Shadows expose the formative pressures on her sensibility, the way fear, fragility, and an almost militant tenderness co-inhabit the same soul. The story “The true story of Heidegger the fox,” a 1953 entry in Arendt’s Denktagebuch, conducts in fable what the letters do in address: it inverts, plays, stylizes the inexhaustible question of who the other is and how to remember him without either idolatry or denial. What appears marginal becomes central: it is in these minor genres that the disproportion of the archive is, in part, corrected, and the reader can receive her voice not only in drafts of letters but in forms she chose for herself.

A persistent claim of the book is that writing here is not a supplement to life; it is the form life takes when it faces what shatters it. When the editor remarks that for both writers the work was generally more important than the life, the obvious objection—that the letters contradict that valuation by foregrounding life—misses the point. The letters are not the raw opposite of work; they are the mode in which the work survives its conditions. To say this is not to ennoble gossip; it is to recognize that, for thinkers whose concepts of thinking and judging are irreducibly worldly, the world’s intrusion into the letter is the very material of concept formation. For Arendt, understanding is contemplation, confrontation, critique; for Heidegger, a couplet about Being flashes its light in rare abruptness. The difference is real; the proximity is irreducible. The correspondence neither synthesizes nor dramatizes the difference; it lets the difference endure.

Even micro-episodes offer concentrated matter for reflection. The practicalities around Kassel lectures, the request to bring Scheler, the exchange of photographs, the preoccupation with seating in a lecture hall—these details are not trivia. They locate thinking in the ecology of everyday arrangements, in which ideas travel not in theses alone but in trains caught at wrong hours, in rooms too noisy for a desk, in benches after concerts where speech is impossible and therefore truthful. When Arendt writes that she cannot say “you don’t understand that” because the other “senses” and “follows along,” the sentence refutes a pedagogy of explanation; it claims, instead, a pedagogy of accompaniment. When Augustine appears not as doctrine but as a sentence calibrated to re-align an ethos—I love you; I want you to be what you are—the archive records not antiquarian taste but an attempt to retrieve the antiquity adequate to the modern catastrophe. The repetition of motifs—lilac over old walls, tree blossoms welling up in secret gardens, mountain precipices above silent lakes—can feel excessive until one notices that only such images stabilize a discourse that otherwise flirts with abstraction. The pastoral is not escape; it is a counter-pressure against the analytic violence that the century made second nature.

The question of publication—why, how, and with what right—haunts the entire enterprise. The foreword narrates the sequence by which the letters’ existence became widely known, the controversy surrounding an earlier biographical treatment that isolated the affair, the deliberations of executors on both sides, and the final decision to publish to forestall sensationalism with documentation. It is lucid, too, about the role of intermediaries and trustees, about the fact that, without Arendt’s preservation and transfer to archives, the exchange would have vanished or remained rumor. What results is a paradox Arendt would have grasped with dry pleasure: that the public sphere is here invoked to defend privacy from trivialization, that the best available defense against the culture of secret-mongering is not more secrecy but a calibrated exposure disciplined by scholarly apparatus and a call for independent judgment.

If one asks what this correspondence does to our philosophical understanding of each writer, two responses suggest themselves, neither flattering to simplification. On the one hand, the letters threaten to confirm every suspicion of the biographical fallacy, inviting the lazy deduction from private phrasing to public doctrine. On the other, they tempt the reader into the polemical use of fragments as weapons for or against either figure. The only adequate reply is to read the letters as documents in which a concept tests itself against the pressures that would trivialize it. In Arendt’s late letters, one hears the clarity about vita activa and vita contemplativa not as slogans but as disciplines she renews against fatigue and loss. In Heidegger’s late dedications and brief notations, one hears the altered ambition of a thinking that renounces system and nonetheless fights for exactness. The final effect is to make both writers less usable as emblems, more burdensome as companions.

There is, finally, the irresistible geometry of dates that the foreword risks and then corrects: the symmetry of the half-century, the significance of 1950 as central to both the decade count and the century itself, the triptych of first sight, second look, and autumn as a temporal form that transposes biography into ethos. The editor wisely refuses numerology while allowing the reader to feel the charm of pattern. The last gesture—a telegram to Hans Jonas mourning Arendt, a letter that follows—extends the correspondence beyond its two names, re-embedding it in the network of friendships and enmities, of philosophical alliances and ruptures, that constitute a life in thought. The letters end, and yet the world that enabled them does not; it demands to be judged again, and the letters—so modest, so performative of restraint, so ambiguous in their blend of tenderness and reticence—remain available as a severe school for the kind of judgment that does not cease where gossip begins but learns, instead, to withstand the appetite to consume what it has not earned the right to understand.

To call this book illuminating, revealing, and tender—as the publisher’s description aptly does—is accurate, but insufficient. The illumination is not a floodlight; it is the narrow beam of a lamp one carries while refusing to mistake shadow for absence. The revelation is not exposure; it is what appears when one declines to pry. The tenderness is not confessional softness; it is the hard labor of a language that insists on dignity even when it judges, and on judgment even when it loves. What the book finally offers is not knowledge about two persons that we did not have, but an apprenticeship in the kind of reading that can hold together, without false reconciliation, the claims of thinking and the claims of love under the pressure of a century that made both seem impossible.

If we test the correspondence against the formula with which Arendt once summarized understanding—contemplation, confrontation, critique—we can say that this volume stages all three at once. It contemplates as it refuses haste, confronts as it refuses consolation, and critiques as it refuses the last word. And if we test it against the sentence with which Heidegger describes the suddenness of Being’s light, we can say that the correspondence endures the flash without pretending it is day. The mystery the foreword says “remains untouched” is not a failure of disclosure but the very success of the letters’ genre, which knows that there are experiences—erotic, philosophical, historical—that are falsified when named and yet do not vanish when withheld. The letters do not dissolve that tension; they give it the most dignified form available: a language that keeps faith with what exceeds it.

It is in this sense that the book’s problematic complexity is not an accident but its highest merit. The correspondence is a document in which form is content: restraint as an ethical stance, asymmetry as historical fact, editorial modesty as a polemic against sensationalism, and the sequence of three titled periods as a counsel about how to think after disaster without either dissolving judgment into bitterness or displacing it with absolution. In the end, what the letters show is that the inner life of two major philosophers is not a trove of explanations for their work; it is the work’s most exacting commentary, the place where the grammar of address—you—holds together what theory alone cannot keep from coming apart.

The book closes with the quiet of its last dates, but it does not close the question the letters pose: how to sustain, over decades and across catastrophes, a form of speech that neither denies the past nor allows the past to monopolize the future; how to accept the incompleteness of what we possess without adorning the gaps with fantasies; how to remember with enough exactness that judgment becomes possible, and to judge with enough humility that remembering does not drown the living. That the letters accomplish any of this is already remarkable; that they do so while remaining tender throughout is their most severe instruction.

Leave a comment