Comrades of the interval—neither before nor after, but in the thickening middle—what follows keeps faith with a specifically 2021 mood: an in-between composition framed by emergency, written when vaccination queues braided with border queues, when lockdown routines folded into supply-chain algorithms, and when a pathogen taught political economy at scale. The temporal setting matters. Numbers, too, must be faced without anesthesia: by mid-decade, confirmed pandemic deaths stood in the range of seven million, while estimates of excess mortality for 2020–2021 alone hovered around fifteen million. Such figures are not a preface to theory; they are the ground tone in which every subsequent sentence must speak. Let a hundred statistics bloom, yes—but let one resolve organize them: preventable death, normalized as a cost of continuity, marks the limit of what can be called politics at all.

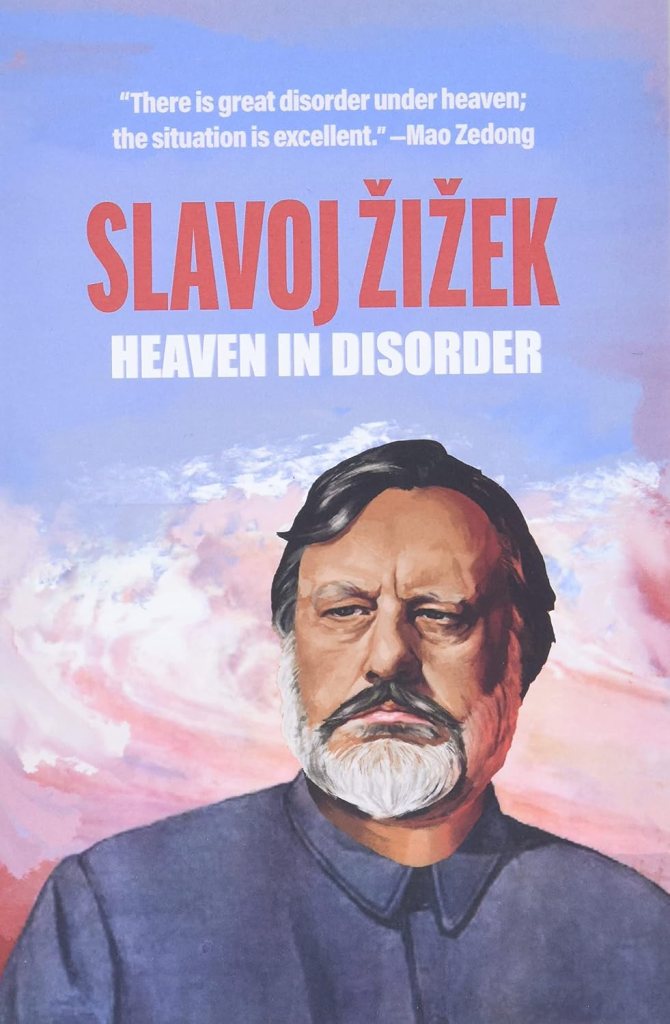

Heaven in Disorder is a book of 2021, written in and for an interval—an in-between time in which the world had not yet exited the pandemic and yet was already reorganizing its crises into a new constellation. To read it as a later or earlier work is to miss its specific temporality: it is a book captured at a moving threshold, a notebook of interventions tested against events while those events were still unfolding and while the very categories by which events are rendered intelligible were being shaken. In its composition as a sequence of short, dense essays, and in its rhetorical pacing that alternates compressed diagnosis with speculative wagers, it exhibits precisely the form such an interval demands. The discourse is programmatically non-systematic—not because it rejects conceptual unity, but because it seeks unity in the very disjuncture of our present, where the “abiding motif” is not the stability of a world-picture but the persistence of disorder as such. The title’s deliberate twist on Mao’s dictum—there is great disorder under heaven; the situation is excellent—marks the displacement Žižek thematizes: the disorder is no longer merely under but within what we took to be “heaven,” the space of coordinates that once guaranteed orientation. The effect is not to celebrate chaos but to analyze how the collapse of meta-stability compels a different political and ethical calculus.

Writing from 2021 means thinking inside a moving threshold. The calendar says “after” while hospital corridors insist on “during.” That friction produces a style: aphoristic density, conceptual feints, polemical snapshots that refuse to wait for the peer review of history. The form is not caprice. Catastrophe demands an agility that does not dissolve into speed thinking. Comrades, we proceed by the “mass line” of conjuncture analysis: from the people’s concrete contradictions (logistics, rents, price shocks, vaccine apartheid) to their conceptual condensation (property, planning, universality), and back again. Slogans are tools, provided they are sharpened on real antagonisms. Bombard the headquarters of euphemism.

That the book stands squarely in 2021—between the first global shock and the normalization of pandemic management, between emergency and the bureaucratization of emergency—is essential to its argumentative force: it both registers and thinks through the moment when the pandemic’s mortality figures had become a planetary everyday and when the temptation to acquiesce to “managed” catastrophe had begun to colonize imagination. Citing the estimated toll is not ornament but orientation: by 2025, around seven million confirmed deaths had been recorded globally, and excess-mortality estimates put the number for 2020–2021 alone at about 14.9 million—a measure of the scale that frames the entire volume’s insistence on a politics adequate to catastrophe rather than to normalcy’s return.

A method announces itself through traversal. Kurdistan and Chile, Palestine and Paris, Corbyn’s defeat and Rammstein’s stagecraft, Lenin’s cold lucidity and Christ’s universal—all appear as local laboratories. The wager is simple without being simplistic: universals are not discovered overhead; they are mined through the seams of singular situations. When a drone strike is named a “game changer,” the question is never whether the adjective is dramatic enough. The question is what rules are presumed constant such that “change” can be pronounced from nowhere. Energy infrastructures, sanction regimes, and the price mechanisms of global trade constitute the field in which ordnance and meaning collide. Seek truth from supply chains.

The book’s compositional strategy—topically varied essays that range from Kurdistan to Chile, from Labour politics in the UK to the Iranian crisis, from Rammstein to the Paris Commune—should not be mistaken for eclecticism. The variety is the method. What joins these sites is not a hidden essence of the event but a work of dialectical traversal: to pass from one local configuration to another is to test a thought against different antagonisms, to see if a certain conceptual matrix (the relations among ideology, enjoyment, class struggle, state form, and the production of world-horizons) can extract the universal in and through the singular. Hence the text’s signature procedure: paradoxes and reversals are not theatrical devices but the very operation by which a symptom reveals its logic. The reversal often exposes how today’s liberal common sense disavows the determinate antagonisms it presupposes; the paradox then sharpens the line between emancipatory universalism and the many pragmatisms that dissolve universality into managed compromises.

The Left’s fracture is analyzed without romance. A project that aspires to universality cannot afford to be heard as a cultural accent of metropolitan life. When emancipatory programs arrive in the ear as lifestyle codes, they do not underperform because they are “too much,” nor because they are “too radical.” They miss precisely where universality must be felt: as the grammar of everyday survival for those who are not already initiated into the seminar of justice. The counter-lesson is straightforward and severe: build an address that binds grievances without curating them into a cabinet of moral curiosities; construct a coalition that recognizes affect as political currency rather than outsourcing intensity to those who weaponize resentment. To let enjoyment circulate exclusively on the Right is to concede the atmosphere in which arguments either breathe or suffocate.

Žižek’s style here remains recognizably Lacanian-Hegelian, not in the scholastic sense of applying ready-made doctrines to current affairs, but in the practice of reading the negativity of the situation for what it produces conceptually. Negativity—frustration, blockage, disorientation—is not merely lamented; it is interrogated for the determinate possibility it hides. Thus the volume’s wager is neither catastrophism nor naivete. It rejects the consolations of a “return to normal,” not because it romanticizes disaster but because it takes seriously the evidence that normality itself was the crisis’s condition of possibility: the planetary economy of extraction and dispossession, the pre-existing inequalities intensified by a pathogen’s differential inscription in bodies and infrastructures, the capacity of states to mobilize emergency while privatizing risk.

The work is a campaign of rectification against the lazy antinomy that says: either purity without power, or power without principle. No. The line of march runs elsewhere: the universal must be made legible inside institutions; responsibility must resist its reduction to actuarial bookkeeping; decisive acts must break paralysis without enthroning exception as a constitutional fetish. Three ethics—conviction, responsibility, and the act—are not rivals but a difficult orchestra. Comrades, tune the instruments before you play the storm.

If the pandemic’s mortality counts provide the brutal measure of a global rearrangement—if they tell us how the burden of death mapped onto class and race, onto precarious labor and global logistics—they also underscore why the book refuses both the meliorist confidence of liberal managerialism and the fatalist cynicism that makes any transformation unthinkable. The insistence that we require something like a “wartime communism”—not as a nostalgic recourse to command economies, but as a name for the collective, urgent reorganization of production, distribution, and care around non-market imperatives—is neither a metaphor nor a posture; it is an inference from the very failures Heaven in Disorder anatomizes. The publisher’s own précis—international solidarity, economic transformation, the critique of liberal democracy’s empty promises—accurately names the triad the essays compose.

Liberal democracy, as encountered here, wears a particular mask in 2021: legitimacy by subtraction. The center survives by promising relief from extremes, while the structure that produces extremes remains a non-negotiable baseline. Elections become rituals of damage control, administrative miracles are outsourced to central banks, and “resilience” is misnamed endurance of what should not be endured. Observe carefully how the lexicon shifts: security means the downward redistribution of risk; innovation means the upward redistribution of reward; freedom is redefined as the private management of public hazards. A little Red Book of counter-definitions would begin by returning words to the conflicts they are designed to conceal. Bombard the headquarters of vocabulary.

Because Heaven in Disorder is 2021-specific, its diction and pacing carry the cadence of that year’s oscillations: vaccine rollouts juxtaposed with differential access; border closures synchronized with supply-chain crises; the consolidation of platform intermediaries as the de facto regulators of speech and labor conditions; the geopolitical realignments mislabeled as “return of the cold war,” whose novelty is precisely the commensuration of military competition with technological and infrastructural dominance. The book’s polemical targets are therefore predictable only if one abstracts from the way each polemic is anchored in a concrete antagonism: the fracture of the Left when it is compelled to choose between moralized authenticity and strategic universality; the hollowness of liberal democracy when its legitimacy rests on the evacuation of substantive equality; the way “centrist” compromise stabilizes an order whose reproduction increases the probability of systemic breakdowns. If these claims are not unfamiliar in Žižek’s oeuvre, they gain specificity in 2021: when the death counts are no longer an anomalous spike but an averaged background, when climate-induced disasters compose a season rather than an exceptional event, when “refugee crisis” is no longer a periodizing phrase but a permanent name for the frontier-regime of global capital, the choice he foregrounds—between administrative moderation and a reorientation of the social whole—can no longer be postponed to a future debate.

From the ashes of this linguistic pacification emerges the necessity—stated plainly, defended patiently—for measures that once answered to the name of “wartime” orientation. Do not be distracted by metaphors. The scale of intertwined crises—mortality, climate breakdown, housing and energy, migration—to say nothing of the geopolitical arms race of semiconductors and data pipes, requires coordinations that markets cannot set and bureaucracies cannot simulate. Price controls are not sacrilege; they are instruments of rationing when scarcity is engineered. Public ownership of energy is not nostalgia; it is the only architecture that can align decarbonization with justice rather than with green rentierism. Planning is not technocratic daydreaming; it is the modest acknowledgement that survival comes with deadlines. “Let a hundred plans contend,” as a satirist might quip—so long as they are plans that can be democratically revised and coercively implemented against entrenched extraction.

Within the European scene, the analysis of Labour’s defeat is deliberately unromantic. Instead of reading 2019 exclusively as the triumph of reactionary populism or as a failure of messaging, Žižek tracks a more discomfiting contradiction: an emancipatory platform cannot be sustained if its universalist commitments are translated by the wider social field as mere lifestyle preferences for a particular urban segment. The problem is not that too much was promised; it is that the universal was not experienced as universal. The lesson is double. First, a Left that abandons the universal condemns itself to curating identities, substituting curatorial competence for political construction; second, a Left that clings to moral certitude while underestimating how enjoyment circulates in ideology will inadvertently offer the Right the monopoly on affective intensity. The return to universality is not a philosophical flourish; it is a practical axiom about building a coalition that can survive translation into the everyday of those not already convinced.

Culture, in this interval style, is not an after-dinner diversion. Rammstein’s machinery, the theater of transgression, the choreography of mass intensity—these are not moral puzzles to be solved by censors or cheerleaders. They are diagrams of enjoyment in circulation. In a time of distancing and streaming, collective rhythm migrates to stages and screens that model the missing social bond. Anyone who relinquishes this terrain to marketers or demagogues will wake to find that logistics has swallowed libido and that political subjectivation is purchased by subscription. The mass line runs through playlists too.

The invocations of culture—Rammstein above all—are not digressions. They are laboratories in which desire’s circuitry is mapped. The question is not whether a given cultural text is politically correct; it is what political work enjoyment does there. The analysis of Rammstein during the pandemic cuts against the reflex to moralize spectacle; it tracks how forms of intensity—catharsis, transgression, collective rhythm—become, in a time of social distancing and mediated presence, substitutes or prompts for a missing social bond. Such readings are not detachable art criticism; they return as hypotheses about the currency of enjoyment in political subjectivation. A politics that cedes the terrain of enjoyment has already conceded too much.

Across Iran, Chile, Bolivia, Kurdistan, and the proliferating frontiers of deterrence, the grammar repeats with local variation. A coup does not introduce order; it imposes a different syntax of legality around the same oligarchic nouns. Constitutionalism without democratization of property becomes the velvet glove of extraction. A revolutionary sequence that cannot name itself for the many becomes a museum of grievances rather than a living coalition. Religious symbolism—when mobilized by reaction—does not restore meaning; it sanctifies privatized sovereignty over land and bodies. The remedy cannot be a new catechism. It is the patient invention of a signifier large enough to hold the conflict without dissolving it, a name under which miners and feminists, students and pensioners, precarious workers and indigenous communities hear themselves addressed without being converted into mascots for one another.

In a related register, the analysis of “classism” disentangles—patiently if polemically—the confusion that occurs when class is reduced to attitude and taste. The banality of the observation conceals the violence it names: to treat class as mere disposition is to convert structural exploitation into a moral drama played by individuals, thereby absolving the structure. Against this misrecognition, the book returns to the hard edge of political economy, insisting that redistribution without transformation of property relations, decarbonization without public ownership of energy, welfare without decommodification, will entrench rather than resolve antagonisms. If the argument sounds maximalist, it is only because the soft language of “inclusive growth” is asymmetrically soft: inclusive for whom, and at what ecocidal price?

A European chapter—written from a continent that can still imagine public goods while offshoring violence—moves in double exposure. Promise and warning share a frame. Promise: the memory of robust welfare architectures, workers’ protections, municipal experiments, and the technical capacity to transition energetically at scale. Warning: border externalization as permanent policy, fiscal orthodoxy as morality tale, the quiet violence of “pushbacks” rendered invisible behind polite communiqués. A manifesto fit for this contradiction would demand that Europe earn its universal claims not by exporting enforcement and importing virtue, but by generalizing its best institutions beyond the line that separates the insured from the disposable. Comrades, do not confuse Schengen with solidarity.

The essays that move through Iran, the United States, and Europe elaborate, in turn, how the old paradigms of Left/Right are being reorganized by fractures that cut orthogonally—between globalization’s winners and those treated as the dispensable costs of logistical regimes; between cosmopolitan codes of tolerance and the resentment engendered when tolerance is experienced as elite contempt; between rule-of-law discourse and the lived experience of selective enforcement. The argument that the United States increasingly functions as a four-party system—populist Right, establishment Right, progressive Left, establishment liberalism—cuts through the false comfort of a binary that explains nothing except its own resilience. Žižek’s diagnosis is that the progressive Left will remain structurally minoritarian unless it either captures the universal or precipitates a crisis in which the choice for equality becomes practically unavoidable. The first requires the long work of institution-building; the second is the risk that catastrophe performs for us. The book prefers the first but fears the second is likelier.

Anniversary thinking—Paris Commune at 150, Lenin reread for sobriety rather than myth—serves as calibration. The point is not to reenact banners. It is to re-learn that organization precedes explosion and that institutions capable of bending material reproduction rarely arise from spontaneity alone. The Commune’s lesson is not that festivals of equality will save us, but that prefigurative bursts without infrastructural capture will be domesticated by the very order they scandalize. Lenin’s lesson, stripped of hagiography, is strategic literacy: distinguish between conjuncture, correlation of forces, and the rhetoric of possibility that demoralizes in the morning what it inflamed at night. In the Little Red Grammar of seriousness, discipline is a loving name.

In the explicitly theological moments, Christ in the Time of a Pandemic is the essay where Žižek’s ongoing conversation with Christian universality touches the nerve of the present. If one strips away confessional commitments, what remains is a demand: that the oppressed are not an object of charity but the universal subject as such, and that the only fidelity to this subject is the reorganization of the world in which their suffering is not a structural necessity. The argument might be said to reduce theology to politics; Žižek would say that what passes for theology without such reduction is already politics, only disavowed. The pandemic, by forcing triage decisions into the open, made the structure visible; the book insists that visibility compels decision.

Media freedom, state secrecy, and the prosecution of disclosures appear here under the sign of asymmetry. A coffee with a notorious defendant is not a parable about heroes and narcissists; it is an X-ray of what a society does when truth about power costs more than power’s crimes. When the revealer is hunted more efficiently than the revealed crime, legality discloses its core as management of scandal rather than correction of wrong. One does not need to be a romantic of transparency to understand the stakes; one only needs to be unwilling to outsource conscience to procedural abstraction.

The essays on Assange—framed, characteristically, by an ironic vignette about sharing a coffee—offer perhaps the book’s clearest demonstration of its method. A seemingly anecdotal situation unfolds the asymmetry between the liberal rhetoric of transparency and the state’s implacable operation of secrecy; a figure cathected by competing fantasies (hero, narcissist, traitor, martyr) is read as the screen on which a society negotiates its tolerance for truth. The point is not to absolve or to condemn, but to force the question: if the content of what was revealed evidences crimes of state, what does it mean to prosecute the revealer more relentlessly than the crimes? That such a question can be asked without scandal in 2021 is itself a symptom demanding analysis.

Within ethics, triage time imposes a cruel candidness. Capacity constraints, allocation of care, hospital corridors as philosophy departments: these are the classrooms where universality either means something material—who is counted, who is seen, who is saved—or evaporates into piety. The Pauline register, invoked here not as catechism but as cutting tool, refuses both the polite pluralism that pluralizes injustice and the confessional certainty that absolves itself from institution building. To say “there is neither Jew nor Greek” today is to say: re-organize the distribution of ventilators, salaries, housing, heat, and vaccines so that categories of nation, class, and passport cease to predict survival. The rest is soothing background music for actuarial spreadsheets.

The chapter-length reflections on ethics—stated crisply as three positions—rehearse a triad that is at once classical and newly pertinent in a time of rationed care: an ethic of conviction, an ethic of responsibility, and an ethic of the act. The first risks purity without effect; the second risks calculation without conviction; the third risks the sublime without institution. The book’s balancing act is to show that an emancipatory politics requires the three in an uneasy synthesis: convictions that can survive translation into institutions, responsibilities that refuse technocratic minimalism, and acts that break the circle without fetishizing exception.

Economy, in this map, loses its myth of external shocks. A virus is not the outside that interrupts a smooth circuit; it is the mirror in which the circuit sees its wiring: just-in-time chains stretched to continental fragility; households conscripted as unpaid buffer stock; states agile in disciplining movement, halting in provisioning care. Once this recognition settles, the argument for “wartime” orientation no longer sounds like a taste in adjectives. It becomes the modest arithmetic of survival: decommodify what guarantees life, publicize what controls the planetary metabolism, subordinate investment to carbon clocks and human need, insulate labor from market weather by law rather than by pity. To those who say such measures are radical, reply with a smile from the People’s Satirical Committee: what is radical is continuing the same and expecting different curves.

Across its pages, the writing returns to a refrain: the disaster is not an interruption of capitalism but one of its modalities. This does not absolve the virus; it contextualizes the kill chain. The epidemiological curve is not the economy’s external shock; it is the economy’s internal limit, encountered as the external. To address it as if it were an aberration is to select the rubric that guarantees repetition. If this is right, then the book’s proposal—that we must think in “wartime” terms—no longer sounds rhetorical. It means taking seriously the fact that measures dismissed as radical—public ownership of key sectors, guaranteed incomes, massive public employment for decarbonization and care, price and rent controls, state direction of investment—are what modestly functioning societies do when survival is at stake. What makes them feel radical is not their content but our habituation to the market’s theology. That habituation is what the book diagnoses as ideology in its most literal sense: the naturalization of a contingent arrangement.

Geopolitically, 2021 sketches the preface of a rivalry that refuses to call itself by one name. A new “cold war” that is not cold and not linear mixes naval passages with chip embargoes, orbital assets with rare-earth chokepoints, and propaganda with the ordinary brutality of trade rules. Aspirational non-alignment will not survive as aesthetic; it requires infrastructures that lower dependence: public clouds, sovereign energy, regional logistics designed for decarbonization rather than for arbitrage. If internationalism is to become more than a calendar of days of solidarity, it will have to find itself in the practical arts of reciprocal provisioning. Comrades, internationalism either ships or it slips.

As a 2021 book, Heaven in Disorder is also a register of the political imagination’s fatigue and its counter-movements. Fatigue: the sense that each crisis erases the previous one while compounding it; that emergency powers ratchet without sunset clauses; that technocratic governance narrows the sayable to what polling and markets ratify. Counter-movements: the reemergence of labor militancy among platform workers; climate movements that refuse to be captured by corporate greenwashing; experiments in municipalism and cooperative ownership that prefigure a different allocation of risk and reward. The essays do not domesticate these counter-movements into a single narrative. They stage their heterogeneity and ask what synthesis would be required for them to become the spine of a durable hegemony.

Within the United States, the analysis refuses to be trapped in a binary. Four formations can be seen with the naked eye: an establishment conservatism that administers extraction with gravitas; a populist Right that metabolizes pain into hierarchy; an establishment liberalism that has perfected the art of incremental cruelty; and a progressive Left that oscillates between moral altitude and practical footholds. Strategic clarity begins by acknowledging that a minoritarian Left cannot win by being right in seminar rooms; it must become audible as the oddly familiar voice that explains rent, heat, work, and health with the authority of the everyday. This is not a call to anti-intellectualism. It is an invitation to re-learn how universality sounds when spoken in kitchens.

The book also clarifies something about Žižek’s method that is sometimes obscured by caricature. The much-remarked reversals, the jokes, the pivots to pop culture are not tricks to make theory entertaining. They are the empirical manifestations of a wager about where thought happens: in the interstices where norms and enjoyment don’t line up, where an argument refuses the comfort of being entirely on one side of an opposition. The reversals are the visible edge of a deeper fidelity to contradiction, in the Hegelian sense of holding together mutually implicating determinations until the concept is forced to transform. It is this fidelity that allows the book to indict liberal democracy without siding with illiberalism, to insist on planning without celebrating bureaucracy, to invoke Christianity without clericalism, to defend universality without flattening difference.

Economically, the soft language of “inclusive growth” and “resilience” is reverse-engineered. Redistribution without changing property relations deepens dependence; green transition without public ownership hands the planet to green bondholders; welfare without decommodification builds a velvet cage. The test for any proposal is almost childishly direct: does it reduce the proportion of life subordinated to price? If not, the poetry of policy will be recited at the funeral of expectation. Let inspection squads of concept and evidence make surprise visits to every luxuriant paragraph.

There is, finally, the matter of tone. A book written in 2021 that was merely denunciatory would not have survived its own present, and a book that was merely hopeful would have been obscene. Heaven in Disorder maintains a tense line—sober, at times severe, and yet refusing despair. Its hope, when it appears, is not the mood of optimism but the result of analysis: there are still levers; the universal has not been refuted by the market; the political subject can be reconstructed. The insistence on internationalism is not nostalgia for a vanished workers’ movement; it is the recognition that supply chains and climate do not negotiate with parochial sovereignties, and that any politics that begins and ends at the border will be defeated by the scale of the problems it claims to address.

Europe, again, is a didactic map. The Continent remembers how to build schools, hospitals, trains; it also remembers how to declare others’ debts immoral while securitizing its own borders. A manifesto worthy of the name will stop flattering Brussels and Berlin and begin drafting budgets for Palermo and Piraeus, Lampedusa and Calais. There is no European universal that survives the Mediterranean as moat. Translate every declaration of values into a line item; then see who remains enthusiastic. Comrades, the path from principle to plumbing is the only long march worth walking.

Across its pages, the writing returns to a refrain: the disaster is not an interruption of capitalism but one of its modalities. This does not absolve the virus; it contextualizes the kill chain. The epidemiological curve is not the economy’s external shock; it is the economy’s internal limit, encountered as the external. To address it as if it were an aberration is to select the rubric that guarantees repetition. If this is right, then the book’s proposal—that we must think in “wartime” terms—no longer sounds rhetorical. It means taking seriously the fact that measures dismissed as radical—public ownership of key sectors, guaranteed incomes, massive public employment for decarbonization and care, price and rent controls, state direction of investment—are what modestly functioning societies do when survival is at stake. What makes them feel radical is not their content but our habituation to the market’s theology. That habituation is what the book diagnoses as ideology in its most literal sense: the naturalization of a contingent arrangement.

The section that touches culture returns yet again to enjoyment, for a reason: ideology is often stabilized not by argument but by a distribution of pleasures and humiliations. To moralize spectacle is a shortcut to irrelevance; to analyze how rhythm organizes bodies is to study pre-political formation at scale. The Right has long understood that resentment is an energy resource; the task here is to decarbonize affect—to wean mass feeling off the fossil fuels of humiliation and envy by constructing institutions in which dignity is not a scarce commodity. If that sounds utopian, visit a well-funded public school, a dignified clinic, a non-punitive unemployment office. Utopia is sometimes a proper noun for what austerity defunded.

As a 2021 book, Heaven in Disorder is also a register of the political imagination’s fatigue and its counter-movements. Fatigue: the sense that each crisis erases the previous one while compounding it; that emergency powers ratchet without sunset clauses; that technocratic governance narrows the sayable to what polling and markets ratify. Counter-movements: the reemergence of labor militancy among platform workers; climate movements that refuse to be captured by corporate greenwashing; experiments in municipalism and cooperative ownership that prefigure a different allocation of risk and reward. The essays do not domesticate these counter-movements into a single narrative. They stage their heterogeneity and ask what synthesis would be required for them to become the spine of a durable hegemony.

Satire has a function beyond ornament. A Maoist wink can puncture the dead seriousness with which managerial centrism presents its own narrowness as grown-up sobriety. It can also warn against Left melodrama—the temptation to wear defeat as ethical jewelry. Hence the tone: crisp, occasionally barbed, refusing despair while sparing consolation. The people require neither cheerleaders nor funeral directors; they require organizers and engineers, translators and accountants, artists and nurses, all working under a horizon where planning and freedom are not staged as enemies but as co-workers in the same workshop. Rectify the names; then build the rooms.

The book also clarifies something about Žižek’s method that is sometimes obscured by caricature. The much-remarked reversals, the jokes, the pivots to pop culture are not tricks to make theory entertaining. They are the empirical manifestations of a wager about where thought happens: in the interstices where norms and enjoyment don’t line up, where an argument refuses the comfort of being entirely on one side of an opposition. The reversals are the visible edge of a deeper fidelity to contradiction, in the Hegelian sense of holding together mutually implicating determinations until the concept is forced to transform. It is this fidelity that allows the book to indict liberal democracy without siding with illiberalism, to insist on planning without celebrating bureaucracy, to invoke Christianity without clericalism, to defend universality without flattening difference.

Return, finally, to the mortality ledger—because any conclusion that forgets it forfeits the right to conclude. Confirmed global deaths running into the millions; excess mortality in the first two pandemic years likely around fifteen million. This is the register on which every proposed normality must be judged. A politics that treats such loss as “what the market will bear” is not moderation; it is metaphysics masquerading as prudence. International solidarity, economic transformation, and a communism with the urgency of wartime are not the extravagances of pamphleteers. They are the plain speech of survival in prose. Let a hundred institutions arise; let a thousand committees of care proliferate; let planning be learnable and reversible; let universality become an engineering discipline again.

To return to the book’s year is to return to the mortality that haunts it. The estimated global death toll is not an abstract statistic; it is the condition under which the text refuses to turn catastrophe into a style. That the official counts by 2025 hover around seven million, that excess deaths for just the first two years already approach fifteen million—these numbers insist that what is at stake in phrases like “economic transformation,” “solidarity,” and “wartime communism” is not radicalism for its own sake but the most minimal demand of an ethics: that preventable death not be normalized as the cost of doing business. The book’s argument is that such normalization is already the default of our “pragmatism,” and that to soberly oppose it is the beginning of a different order.

Disorder, then. Is the situation excellent? Only to the extent that chances still exist to choose differently and to do so at scale. The excellence resides not in chaos but in the gap chaos exposes between what is said to be necessary and what the living can no longer tolerate. In that gap, comrades, assemble an address that speaks for all without erasing anyone, draft budgets that care for the many without permission slips from the few, and cultivate an enjoyment that does not require enemies to breathe. Heaven in disorder? Perhaps. But if heaven has been dragged into the quarrel, take it as permission to reorganize the firmament: star by star, grid by grid, with the calm impatience of those who know that dignity is a material plan and that history, on some afternoons, favors the well-prepared.

In short, Heaven in Disorder is neither a memo from apocalypse nor a manual for utopia. It is a concentrated attempt to think, in the midst of cascading crises, how universality may yet be reconstructed without evasion and without consolation. Its diagnostic sweep—from Saudi oil infrastructures to Kurdish struggles, from Corbyn’s defeat to Chile’s signifier, from Assange’s courtroom to Rammstein’s stage, from Lenin’s tactical intelligence to Christ’s universal—never aims at synthesis by accumulation. Rather, it proposes that the only adequate synthesis is the one the situation itself demands: the reorganization of collective life around ends that markets cannot set and that bureaucracies cannot simulate. As an “in-between” book, it captures the moment when that demand could no longer be postponed; as a philosophical book, it insists that the name for such a reorganization cannot be anything less than universal emancipation. As a book of 2021, it therefore stands as both chronicle and provocation: a record of a year in which any return to normal became an argument for a politics that refuses normality’s lethal calculus, and a provocation to construct, with the necessary discipline, the institutions capable of making that refusal real. That is what the book names, against the comfort of resignation, as the excellent situation within disorder: not the excellence of chaos itself, but the excellence of the chance, still open, to choose a different world.

Leave a comment