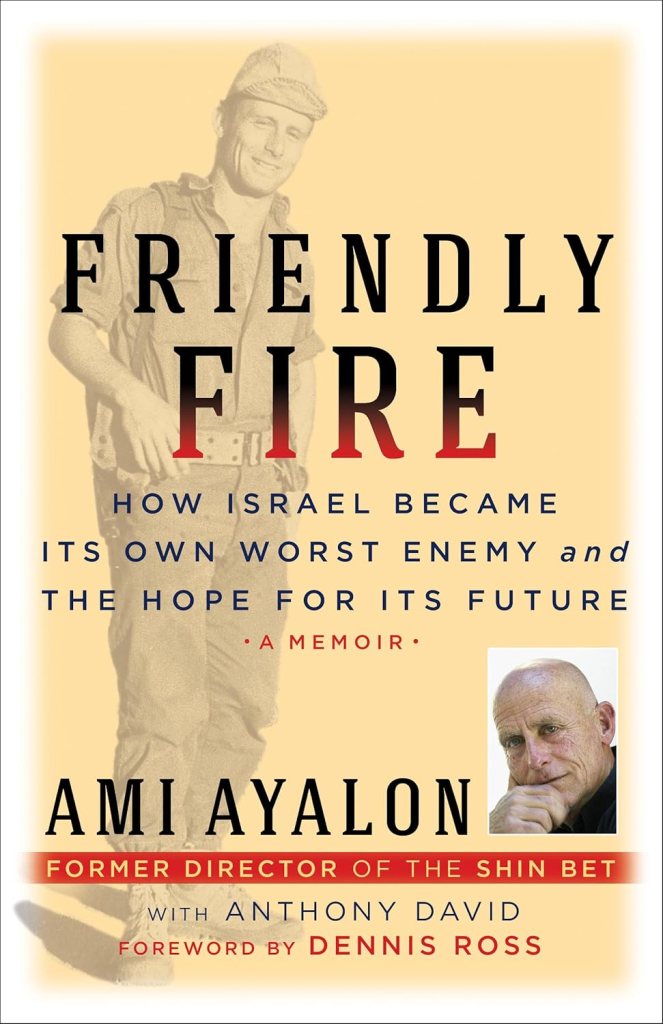

In Friendly Fire: How Israel Became Its Own Worst Enemy and the Hope for Its Future, Ami Ayalon’s deeply personal reflections combine with the political realities, strategic conundrums, and psychological evolutions that have shaped both his own life and the state he has served so profoundly. The book’s pages carry the weight of his vast experiences and broad emotional landscapes, starting in the crucible of his youth on a small cooperative moshav and culminating in his tenures as commander of the Israeli navy, director of the Shin Bet, and an elected official in Israel’s Knesset. The story is at once intimately autobiographical and grandly panoramic, weaving a chronicle of personal metamorphosis into the urgent drama of a larger national struggle. Throughout this layered narrative, coauthor Anthony David’s skillful historical grounding and Dennis Ross’s contextual foreword illuminate Ayalon’s candid testimony, situating it within a wider tapestry of contemporary policy debates, diplomatic dead-ends, and the inescapable imperatives of human conscience. The result is a chronicle of remarkable depth and courage, hailed by many, including the National Jewish Book Award committee, as a vital contribution to an ever-expanding literature that grapples with Israel’s complex identity and precarious future.

Readers stepping into these pages discover a paradox: Ayalon devoted himself wholeheartedly to the defense of his country from the moment he joined the storied Flotilla 13 in the Israeli navy—the naval commandos—at a young age, and he went on to achieve the highest distinctions, including the Medal of Valor for his role in the 1969 Green Island raid. Over the years he spearheaded bold and often lethal missions, operating under the conviction that firm military action against existential threats was not only a strategic necessity but also a moral duty. Yet in “Friendly Fire,” he recounts the slow, fraught dissolution of that black-and-white mindset, brought about by an empathic reckoning with the Palestinian people he once reduced to faceless adversaries. Through introspection and conversation with friends, enemies, and critical commentators, he recognized that Israel’s efforts to thwart terror while simultaneously allowing hopelessness to take root among its Palestinian neighbors inevitably breed the next cycle of violence. As he poignantly concludes, a population with nothing to lose will rally behind extremism because there are no tangible alternatives, and any short-lived success that Israeli security agencies might achieve on the ground becomes self-defeating in the wider political context.

Over the course of the narrative, Ayalon reveals how his time as head of the Shin Bet (sometimes referred to as Shabak) pushed him to question longstanding notions of victory and safety. He describes how, within interrogation rooms and during covert operations, he came face-to-face with the agony, the anger, and the desperation of the Palestinians under occupation. Working in the hidden corridors where intelligence merges with moral ambiguity, he discovered that brute force alone would never secure the peace and stability his country longed for. Rather, it risked corroding Israel’s democratic values and turning the national ethos away from pluralism and empathy, replacing it with perpetual fear and reflexive aggression. In these chapters he delves into the moment when he realized that the humanity of the other side—once invisible to him—was as real and immediate as that of his own comrades. The book recounts, with disarming frankness, the pivotal epiphany that came from facing those whom he had previously deemed irreconcilable enemies, and from seeing how the dull ache of humiliation twists into collective rage and frustration.

Running like a leitmotif across all these pages is a sobering warning: If Israel cannot reconcile its national security with its humanistic core, it is fated to become an Orwellian dystopia, a place in which fear itself erodes civil liberties, poisons relations with both allies and neighbors, and saps the moral energy on which the state was founded. Ayalon, whose background in the most elite units once instilled in him a near-unquestioned patriotism, confesses that years of service built a blind spot in his perspective. He narrates how he came to see that settlers, secular progressives, religious nationalists, and hawkish leaders inadvertently feed the same cycle by ignoring the voices of Palestinians who are themselves eager to end the violence. Recounting episodes of collaboration and conflict with key Palestinian figures, he illuminates the irony that, even among the so-called intractable foes, real partners for peace existed—only for both sides to sabotage these possibilities through stagnation, fear, and cynical leadership.

The breadth of editorial praise for “Friendly Fire” underscores the book’s significance. Critics at The Times of Israel remark upon its “idealistic, yet sober and realistic, vision of what is needed to advance the prospects of peace,” while Kirkus Reviews highlights the combination of Ayalon’s extraordinary achievements with a sense of determined optimism. The Guardian lauds the memoir as “smoothly written” and “compact,” noting that it also reads as a microcosm of Israel’s own modern history. Haaretz speaks of the text as a profound philosophical odyssey, delving into the evolving identity of Israel, Zionism, and Jewish tradition. The Nation points out that the book does not just trace a personal odyssey; it demands that Israel truly acknowledge the story of Palestinian exile and recognize the necessity of a two-state solution. Such appraisals converge on the notion that Ayalon’s authenticity—rooted in rigorous security credentials—imparts an unusual authority to his stance, especially as he bluntly contradicts hardline narratives that entrench mistrust.

The labyrinthine story of modern Israel runs through every page. As Ayalon recounts in the excerpted prologue, he once believed that empathy for the so-called enemy was tantamount to betrayal. Reflecting on how the horrifying lynching of two Israeli reservists in Ramallah unleashed fury in Israel, he confesses that the public backlash against him in that same moment was unrelenting, since he dared to suggest on live television that the despair in Palestinian society gave militants endless recruits. Israel’s national psyche, with its deep scars from wars fought since 1948 and from atrocities targeting Jewish communities in prior centuries, had taught him from childhood that security could be guaranteed only by overwhelming force. This belief, bred in the crucible of state-building and open conflict, formed the rationalization behind missions he undertook or ordered for decades. The gift of this book is its depiction of how he broke through that hardened shell. No stranger to risk or to operational secrets, he reveals that the existential threat to Israel lies not only in external enemies but also in the corrosive effect of occupation and denial of the other side’s narrative.

The foreword by Dennis Ross, a diplomat who has dealt with Middle East peace negotiations across multiple U.S. administrations, contextualizes Ayalon’s stance in the broader story of failed summits, missed opportunities, and personal leadership encounters. Ross recalls visiting Shin Bet headquarters, where Ayalon invited officers with differing attitudes—some militant, some sympathetic—to debate in front of a prominent foreign mediator. That intellectual pluralism, Ross suggests, epitomizes Ayalon’s brand of “intellectual honesty.” The dual vantage point of fighting militant organizations on one hand and meeting with negotiators on the other gave the Shin Bet director a rare vantage of a conflict that extends far beyond gunfire and arrests. But as “Friendly Fire” illustrates in sobering detail, wise intelligence judgments and empathy alone cannot bring an end to the entrenched power struggles that subvert meaningful compromise.

The book’s remarkable cast of voices—figures such as the Palestinian academic Sari Nusseibeh, who co-founded the People’s Voice peace initiative with Ayalon; Egyptian intelligence officers with whom he sparred in clandestine missions; and Israeli settlers who champion biblical imperatives over pragmatic diplomacy—reveals how messy, impassioned, and deeply personal the Israeli-Palestinian conflict becomes when stripped of abstractions. The author’s reflections on his own childhood home, built upon remnants of an Arab family’s pre-1948 property, underscore how physical traces of the past persist, silently accusing or inspiring, depending on one’s vantage. He warns that for Israelis to fail to grapple with these unacknowledged histories is to build layer upon layer of distrust. If fear and denial take hold, they transform well-intentioned patriots into foot soldiers of a dystopia, normalizing violence and hostility in the name of security.

Equally striking is how Ayalon, consistently described by colleagues and critics as a realist rather than a romantic, dismantles the convenient illusion that Israel, or any other democracy, can subdue or silence millions of oppressed people by power alone. As he relates with disarming candor, the intangible but irreducible element of hope is a vital security asset, one that cannot be supplied by bullets or barbed wire. Far from equating moral concerns with naïve pacifism, Ayalon insists that ensuring Palestinians do not believe they are condemned to endless subjugation is not a concession but a strategic necessity. Just as a population convinced of being unloved by the world turns to radicalism, so can a society that believes cruelty is the only language the enemy understands lose its moral and civic bearings. In this regard, “Friendly Fire” is not just a veteran’s life story but an urgent manifesto that calls upon Israelis to rethink how their policies shape, and often undermine, their own long-term security and democratic values.

Many commentaries, including in Modern War Institute, highlight how the book indicts popular political rhetoric that recasts moral qualms as signs of weakness. Ayalon’s own story testifies that refusing to kill indiscriminately and pausing to listen to one’s adversaries are not signs of naivete, but demonstrate the clarity needed to distinguish real threats from illusions. Yet while “Friendly Fire” vibrates with moral seriousness, it never lapses into illusions that the Palestinian leadership is blameless or that Palestinian terrorists are anything but lethal. The author remains unsparing in his recall of suicide bombings, cross-border attacks, and violent rhetoric from extremist factions. His target, rather, is the self-sabotaging short-sightedness of Israeli governments whose blinkered policies feed Palestinian despair, guaranteeing a recruitment bonanza for groups such as Hamas and Islamic Jihad. To him, effective counterterrorism is bound up with a commitment to preserve the humanity of innocents on both sides—a perspective so radical that it outraged many who once admired his operational courage.

Critics in The Guardian and The Nation observe that Ayalon’s lifelong transformation resonates powerfully in a modern Israel beset by polarized debates. His verdict, echoed by some Palestinians who still remember the People’s Voice petition calling for two states, is that mutual recognition of each side’s nationhood and dignity offers the only viable path to permanent peace. Anything less leaves Israel to choose between being a Jewish-majority state that represses and disenfranchises its Palestinian subjects, or else a democracy that forfeits its Jewish character by granting full citizenship to all within one state. The sense that time is running out animates many of Ayalon’s pages, imparting them with both an urgency and a heartbreak. He holds that once a creeping annexation or an unyielding occupation swallows the West Bank in full, no lines can be redrawn except through violent rupture.

Ami Ayalon, in retelling stories of crawling through frigid waters for dangerous missions or grappling with the harrowing knowledge gleaned from Shin Bet interrogation rooms, does not flinch from detailing lethal success or from admitting his share of mistakes. Yet this is not a memoir seeking absolution, nor an attempt to cast blame on any single group as solely responsible. Rather, it is a brave reckoning with the complicated truth that modern Israel, conceived as a haven and symbol of Jewish self-determination, can be imperiled by its very successes in war and by the fear that war seeds in the national psyche. The resonance of that argument explains why critical voices, from Israeli dailies like Haaretz to The Jewish Chronicle, have called the book “optimistic” even as it catalogues the tragedies that might lie ahead if the status quo continues.

Friendly Fire refuses the comfort of simplistic platitudes, insisting that true resolution demands frank conversation about the Nakba, the legitimacy of Palestinian national aspirations, and Israel’s own historical narrative. The prologue references the actual terrain surrounding Ayalon’s home—one structure after another that once belonged to families displaced in 1948—serving as a reflection on the consequences of invisibility and the hazards of clinging to myths that ignore the pain of others. Ayalon’s long journey, shaped by personal trauma and so many funerals, emerges as a microcosm of Israel’s larger spiritual condition. If there is any solace, it is in his enduring faith that hope, carefully nurtured and guided by ethical clarity, can become the bedrock of a more secure and democratic Israel. That same confidence underlies his collaboration with Sari Nusseibeh and his conviction that grassroots campaigns can still shift the hardened political stalemate. Through extensive firsthand experience, he has seen how even sworn enemies might agree on common interests if they believe that the door to freedom is not permanently barred.

In reading Friendly Fire, one grasps how this rare perspective—a fusion of operational heroism and humbling revelation—stands as a formidable challenge to many conventional views. Within the controversy generated by the book lie Ayalon’s blunt truths: that a liberal democracy cannot preserve its essence while running roughshod over a disenfranchised population, that bridging empathy with security requires seeing beyond hollow slogans, and that silence by the majority serves only to cede the national future to extreme voices. Ami Ayalon’s voice is, therefore, a summons for Israelis and international observers alike to question the habits of fear and reflexive aggression that have undermined serious negotiations and perpetuated bloodshed. The moral conviction at the center of his testimony—that it is neither weakness nor disloyalty to see the humanity in one’s opponent—shines through every page.

The power of Friendly Fire also lies in the resonance of its final exhortations, echoed in the foreword by Dennis Ross. The world has seen countless attempts to resolve the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, from the Oslo Accords to American-led negotiating frameworks. Yet time and again, distrust, crisis-triggering acts of terror, and political leadership lacking the courage to guide public opinion away from maximalist fantasies have hardened positions. This memoir, forged in the tumult of real operations and underpinned by rare moral candor, offers a blueprint for a more pragmatic path. Like many Israeli patriots who once believed that preserving the state demanded only strength and unwavering willingness to strike first, Ayalon presents a diametrically different argument: in war among the people, as modern conflict has become, brute force is more apt to be self-defeating in the absence of a credible horizon of dignity for all. The real “friendly fire” he warns of—policies that shoot down the possibility of peace while claiming to defend the homeland—may undercut national survival more surely than any external foe.

Yet the text is never a simple lament. It is a gesture of hope, a recognition that courage means, in this day and age, championing moral imperatives as vital assets to security. It urges a redefinition of patriotism, one that upholds democracy and humility alongside the capacity for tough operations. Few authors can, in one breath, describe lethal missions from their commando past and, in the next, advocate a deep recalibration of the national narrative. Fewer still can do so with such textured storytelling and personal reflection, revealing the subtle interplay of heartbreak, faith, tenacity, and regret that propels each page. With measured realism, “Friendly Fire” contends that Israel’s survival as both a Jewish homeland and a liberal democracy hinges on an honest reckoning with Palestinians’ plight—a recognition that, in no uncertain terms, any lasting peace depends upon two states that mutually honor each people’s connection to the land.

As a finalist for the National Jewish Book Award, Friendly Fire stands out by harnessing both the adrenaline of an insider’s memoir and the academic rigor of an analyst unafraid to draw unsettling conclusions. It is deeply philosophical, relentlessly accurate, and unremittingly honest, ranging across pivotal war zones, high-level intelligence encounters, corridors of political power, and the farmland of ordinary Israelis and Palestinians. Through every detour into haunting recollections and carefully reasoned policy critiques, the book sustains its moral heart, convinced that only through confronting our capacity for cruelty—only by stripping away illusions—can true security and ethical integrity emerge.

In the end, Ami Ayalon’s narrative transcends the conventional definitions of either a war memoir or a policy treatise. It becomes a testimony that resonates far beyond the immediate Middle Eastern context. That is why so many readers, from diplomats to journalists to ordinary citizens, have found in his words a window onto fundamental questions of nationhood, belonging, and the fragile line between self-defense and self-destruction. Whether one is an admirer of Israel’s bold achievements or a critic of its occupation, the clarity of Ayalon’s moral journey is difficult to ignore. “Friendly Fire” does not flinch from reminding us that it is never enough merely to survive; what truly matters is how a society sustains its soul. And in the tragic, ongoing conflict between Israelis and Palestinians, that may well be the deepest lesson of all.

Leave a comment