Martin Heidegger’s Being & Time, first published in 1927, is one of the most forceful interventions in modern thought, perpetually demanding that its readers revisit the very essence of philosophy by confronting anew the question of Being.

Throughout the twentieth century, it engendered a constellation of interpretive debates across a remarkable range of fields, including psychoanalysis, literary theory, theology, and existential phenomenology, thus revealing at every turn the extraordinary scope of its philosophy. The power of Heidegger’s text resides in its painstaking attempt to disrupt inherited assumptions about ontology by asking, again and again, “What does it mean to be?” and by clarifying that we always seem to have some tacit understanding of being, yet seldom pause to articulate it in its fullness. This question runs deeper than the frameworks of more traditional approaches to metaphysics, precisely because Heidegger insists that the discovery of Being begins from our own situatedness as beings in the world—a situatedness he famously terms “Dasein.” Rather than starting with abstract concepts or external categories, Heidegger describes how human existence is always enmeshed in a context of meaning, so that even the most familiar of our everyday surroundings indicates a primordial layer of intelligibility that we normally overlook.

At the heart of this enterprise is the seminal notion of “being-in-the-world.” This single hyphenated formulation simultaneously defies the easy subject/object dichotomies of earlier philosophies and underscores that one’s existence is never an isolated mental interior but, from the start, is bound up with an environment of concern, practical engagement, and intersubjective relations. Because Heidegger anchors his analytic in the phenomena of everyday life—opening a door, using a hammer, walking along a path—his discussion interrogates the structures that make these everyday moments intelligible in the first place. The work thus constructs a novel vocabulary that can be challenging to readers: it introduces expressions such as “ready-to-hand” (Zuhandenheit) and “present-at-hand” (Vorhandenheit) to differentiate the modes in which entities show up for us. Things that are “ready-to-hand” are experienced as tools suffused with practicality and contextual usefulness, whereas what is merely “present-at-hand” is grasped in a more detached or theoretical way, shorn of the pragmatic references that typically connect objects to our projects. Underlying these analyses is Heidegger’s quest to recast or “destroy” the overly theoretical orientation of prior metaphysics and restore the sheer dynamic of everyday engagement as a fundamental philosophical theme.

This recasting is a principal source of the text’s monumental influence. Indeed, commentators such as Richard Rorty have remarked that “Being and Time changed the course of philosophy,” while others, including George Steiner, place the work in the same lineage of epoch-shaping texts that arose from the deep cultural ruptures of post–World War I Germany, alongside volumes by Ernst Bloch, Oswald Spengler, and Franz Rosenzweig, and even Adolf Hitler’s “Mein Kampf” in the sense that each arose from the same broad crisis of German culture.

Being and Time is thus inseparable from its historical moment, when questions of mass society, the sway of public opinion, and the loss of traditional religious moorings weighed heavily on European consciousness. Heidegger’s investigations are often seen in dialogue with existential theologians and religious thinkers—Augustine, Luther, Kierkegaard—and also with his contemporaries who wrestled with the meaning of individual finitude. Indeed, critics such as Richard Wolin have observed that Heidegger’s discussion of human guilt, conscience, angst, and death, even if “secularized,” resonates with a Protestant inflection reminiscent of Luther, as well as the emphasis on anxiety and authenticity in Kierkegaard’s writings. In exploring Dasein’s fundamental structure, Heidegger thereby implicitly addresses issues of “original sin” or a sense of existential “curse,” but he does so in a distinctively phenomenological idiom that brackets explicit theological claims and instead focuses on our experience of being finite and thrown into a world not of our choosing.

The formal architecture of Being and Time signals that Heidegger sought to craft a work in two main Divisions, preceded by a lengthy and rigorous introduction. The first Division sets out a “Preparatory Fundamental Analysis of Dasein,” examining the ways in which Dasein always interprets itself and its world, while the second Division, “Dasein and Temporality,” treats the theme of time as the ultimate horizon for understanding Being. Though Heidegger originally intended a second volume to include an extensive critique of Western philosophy from Aristotle to Nietzsche, he abandoned this plan. Still, readers can discern the project’s deeper gestures toward a radical transformation of philosophy—a momentous “turn” that influenced later generations of existentialists, poststructuralists, hermeneuts, and deconstructionists. What endures in the published text is an exquisitely dense investigation of Dasein’s existential structures: how we are always ahead-of-ourselves, projecting possibilities into the future; how our facticity means we have been thrown into a particular context that we never fully master; and how our everyday immersion can obscure our most genuine potentiality-for-Being.

From a more explicitly existential standpoint, one of the crucial matters Being and Time addresses is authenticity, a phenomenon that Heidegger connects to being-toward-death. He insists that everyday life is largely characterized by what he calls “the they” (das Man), a social mode of existence in which we often lose ourselves in publicness, gossip, idle talk, and conventional norms, thus relinquishing responsibility for our ownmost possibilities. Authenticity emerges when one resolutely chooses to confront the reality of one’s own inevitable finitude, understanding that no one else can die that death for you. This moment of facing mortality, which discloses the sheer impossibility of further possibilities, can paradoxically free one for a more resolute stance in life. Heidegger’s analyses of anxiety (Angst) and conscience deepen this theme, showing that certain disclosures, normally shrouded by our average everydayness, can break through and illuminate the precarious structure of human existence. Observers such as Wolin or Habermas have underscored how these ideas, especially regarding guilt and angst, overlap with cultural critiques of mass society in the tumult of 1920s Germany. Others, like John D. Caputo and Hubert Dreyfus, point to the intricate theological echoes in this existential analytic, reminiscent of Luther, Augustine, or Kierkegaard, but transposed into a philosophical key.

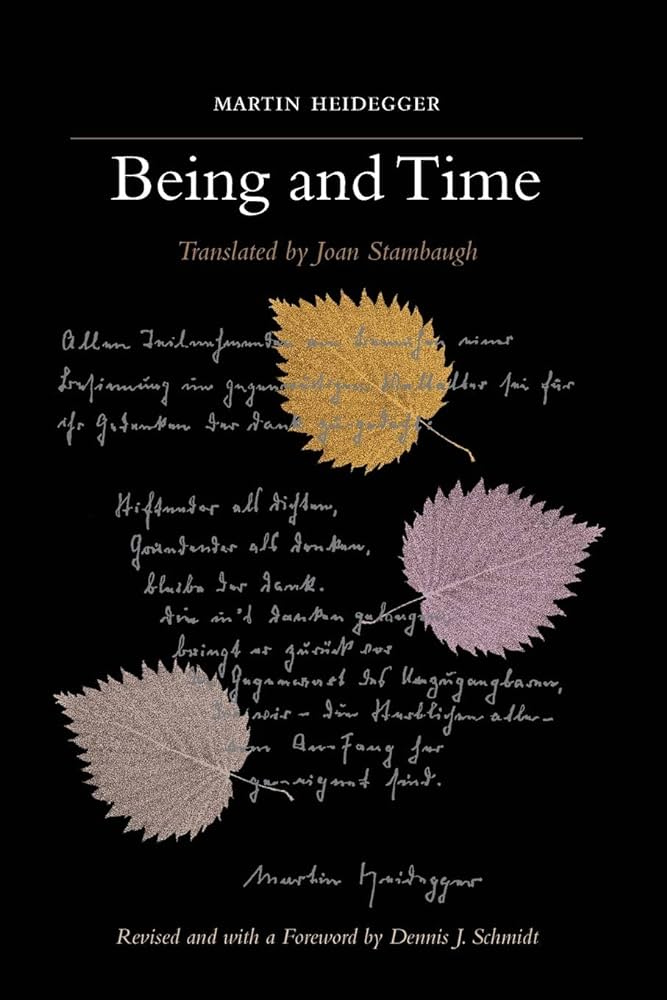

The text’s language can be famously forbidding, for Heidegger is convinced that prevailing philosophical terminology carries sedimented assumptions that distort the phenomena under investigation. Accordingly, he coins new expressions or revives older meanings in German words, generating what many have called neologisms or specialized compounds. This practice invites the careful reader not merely to follow a line of argument but to undergo an awakening to the way language itself shapes understanding. Such verbal density has made “Being and Time” a challenging work to translate and interpret, yet in English-speaking contexts the standard references have long been John Macquarrie and Edward Robinson’s translation, revered for its nuanced attempt to preserve Heidegger’s key distinctions. A later translation by Joan Stambaugh, revised by Dennis J. Schmidt, has introduced bracketed German terms to link readers more closely to the original text’s often untranslatable richness and to consider the marginal notes that Heidegger himself inserted into his own copy. These editorial additions in the Stambaugh version illuminate the dynamic evolution of Heidegger’s thinking, for not only did he compose new layers of commentary in his margins, but he also refined certain passages in the final German edition of 1976. The translator’s challenge consists not merely in rendering individual sentences into another language, but in conveying a wholly unique conceptual framework that discloses phenomena in ways ordinary discourse tends to overlook.

Readers discovering the text for the first time will therefore find that Being and Time demands a measure of devotion rarely called for by other philosophical works. Multiple re-readings often prove essential, as the sense of Heidegger’s precisely formulated arguments deepens only through reflection upon the conceptual architecture he painstakingly constructs. The experience of reading is itself a practice in shifting from everyday ways of thinking to a more phenomenologically attuned approach, where phenomena show themselves in their immediacy. Persistence yields the reward of perceiving, as if for the first time, that our involvement with the tools, tasks, and persons around us cannot be captured by a strictly subject/object schema. Instead, these phenomena reveal a deeper sense of how our very Being is co-constituted by what we do, with whom we do it, and how our environment, or “world,” both shelters and challenges us. In other words, Being and Time refuses to reduce human life to an essence of either interior consciousness or external material processes; it aims to show that the primal reality of Dasein is found in the interrelation of self and world, always already entangled in significance.

This approach has had lasting effects, not only in philosophy but also in anthropology, literary criticism, hermeneutics, existential analysis, theology, ethics, and even psychoanalysis. By unveiling an approach to human subjectivity that privileges the structures of care, possibility, and time, Heidegger stimulated many subsequent thinkers to reformulate what it means to dwell meaningfully in the flux of history. His suspicion of a purely rationalist or scientific stance that fails to consider the depth dimension of human finitude and temporality resonated with phenomenologists looking to expand Edmund Husserl’s emphasis on consciousness. It equally spoke to theologians eager to rethink the nature of faith in light of existential authenticity. Moreover, critics found in Heidegger’s discourse the seeds of ethical and political questions about how “the they” exerts its dominion—questions that took on a darker cast once Heidegger’s own politics came under scrutiny. Yet aside from these controversies, “Being and Time” stands on its own as a major statement of twentieth-century Continental philosophy, one that has deeply impacted the shape of modern intellectual history.

In many ways, the text’s enduring provocation lies in how it shows the inseparability of temporality from the constitution of Dasein. While the earlier sections focus on how Dasein understands itself in the world, the later sections orient that understanding around the tripartite structure of time: we are always coming from a past that is already shaping us, we are engaged in projects that point ahead to the future, and we inhabit a present that never sits still but is formed by the interplay of these temporal ecstasies. By rooting the very intelligibility of Being in time, Heidegger offers a radical counterpart to the tradition initiated by Descartes, who had prioritized space and extension. For Heidegger, the real measure of existence is the existential projection of possibilities in light of our inevitable end. This is why, to read Being and Time, one must grapple with the tension between the everyday anonymity of “the they” and the moment of clarity that seizes an individual when confronted with the undeniable finitude of death. In this confrontation, time emerges as the fundamental horizon for the possibility of disclosure, for in anticipating one’s own demise, one may wrest free from social conformity and experience what Heidegger calls “resoluteness.”

Since its initial publication, Being and Time has triggered both reverence and controversy, and its stature has often been compared to that of works by Kant and Hegel in terms of its magnitude for Western thought. Those uneasy with its dark or elitist resonances, those who question its reticence on certain normative dimensions, or those who wonder about its appropriation of religious themes, continue to keep the conversation lively. Nonetheless, its significance is not in doubt, for it dares to ask—without any simple answers—what it truly means for something “to be,” and especially what it means for us to be the kind of being for whom Being itself is an issue.

The modern reader may encounter Being and Time in different English translations that facilitate subtle glimpses into Heidegger’s shifting emphases and the sometimes maddening intricacy of his diction. Scholars proficient in German often stress the importance of Heidegger’s original coinages and references, suggesting that something crucial lies in the very linguistic patterns of the text. Yet even in translation, the work’s fundamental drive is clear: it aims to awaken a question that philosophy had long obscured or taken for granted, thereby reorienting inquiry at its most elemental level. By bringing to view such concepts as worldhood, readiness-to-hand, Being-in-the-world, thrownness, care, and being-toward-death, Heidegger unfolds a philosophical idiom that continues to captivate, disturb, and illuminate, decades after it first appeared.

The various scholarly editions reflect the continuing efforts of translators and editors to capture the dynamism of Heidegger’s thinking and to retain the freshness of his analyses. The Stambaugh translation, incorporating bracketed German words, helps navigate the multiple meanings that single English words cannot fully convey, while the Macquarrie and Robinson version offers an older but in many ways equally remarkable rendering that shaped English-language Heidegger scholarship for generations. In all these versions, though, one feels the urgency in Heidegger’s pursuit of a way of thinking freed from the unexamined presumptions of metaphysics and oriented toward what it might mean for us to exist meaningfully, to dwell in truth, and to face the ineluctable question of Being.

Nearly a century later, Being and Time still exerts a gravitational pull on any serious student of modern thought. It has become almost impossible to grasp the development of existentialism, hermeneutics, deconstruction, psychoanalytic theory, and a host of other currents without reckoning with the conceptual structures so carefully unearthed here. Indeed, as The Economist once quipped, Being and Time remains Heidegger’s masterwork, and it belongs beside the major monuments of the philosophical canon for the manner in which it compels its readers to release the superficial and plunge directly into the living drama of existence. By turning philosophical inquiry away from abstract theoretical reflection and directing it toward the primal fact of our own Being-in-the-world, Heidegger delivered a text that continues to unveil new meanings, provoking each generation to risk an encounter with the mystery that quietly resonates in the word “Being.” Even amid ongoing controversies about Heidegger’s politics and the interpretive labyrinth of his later writings, this 1927 treatise stands forth as a singular juncture in philosophical history, where the question that animates all inquiry—namely, “What is Being?”—finds one of its most profound and disquieting expressions.

Leave a comment