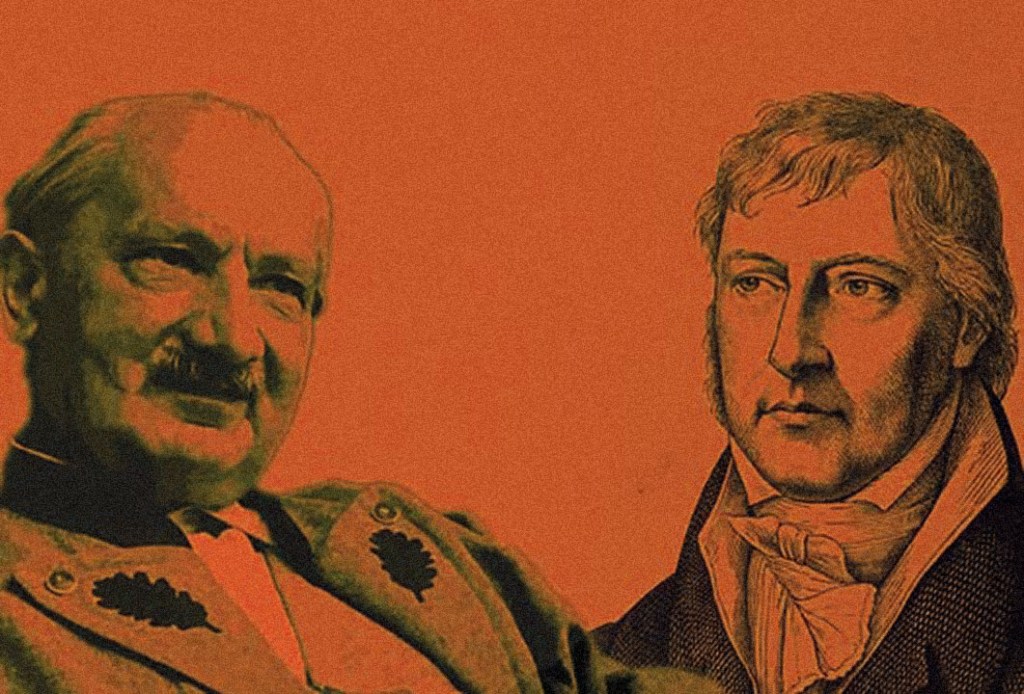

Idealism and the Problem of Finitude: Heidegger and Hegel by Robert B. Pippin presents itself as a penetrating and uncommonly comprehensive exploration of how the post-Kantian tradition, culminating in Hegel’s ambitious “logic as metaphysics,” comes under pressure from a profound critique of human finitude in the thought of Martin Heidegger.

This paper argues that the stakes in “German Idealism,” from Kant through Fichte and especially Hegel, are typically misunderstood if we take idealism merely as a stance about mind-dependence or about the mind-imposed structure of experience, or if we reduce it to some variety of “objective idealism” that prioritizes the immaterial over the material in metaphysical debate. Instead, it suggests that Hegel’s thought—the focal point in the lineage of Kant and Fichte—purports to establish the self-sufficiency of “pure reason,” or pure thinking, in determining all that can be known of anything at all.

Accordingly, for Hegel, reason does not simply legislate within a limited realm of human subjectivity but reaches to the entirety of what is, culminating in the provocative claim that reason’s self-determinations coincide with the most exhaustive sense of being as such: nothing is left beyond the determinate reach of the Concept, so that the “absolute” delimitation of the knowable ultimately amounts to an identity of thinking and being. Yet, as Pippin expounds, Heidegger’s lifework can be read as a multi-pronged challenge to just this paradigm, diagnosing in Hegel—and in the metaphysical tradition more broadly—an enduring unthought, namely the meaning of Being itself and the finitude that defines Dasein’s fragile, historically shaped horizon of intelligibility.

The paper first underscores that Kant, Fichte, and Hegel came to be known as idealists less because they claimed the world to be mind-dependent, and more because they affirmed the power of pure reason to legislate normatively all that counts as knowable. The crucial shift from traditional rationalism to post-Kantian idealism lies in insisting that pure reason legislates its own authority, thereby functioning as a tribunal unto itself. But if, in Kant, such authority remains partly conditional on a thorough interrogation of our sensible, finite mode of intuition, Hegel takes the step that appears to remove any final residue of limitation by declaring that what pure thinking legislates is, without remainder, the entire scope of what can be.

Robert Pippin’s presentation clarifies that this “absolute” dimension of Hegel’s position does not refer to a dogmatic or classically theistic sense of the absolute as a highest being; it rather captures the thought that absolutely no determinacy—no being—escapes pure reason’s norms. In Hegel’s words, the Logic replaces the old metaphysics (the “science of the essence of things”) with a new metaphysics that unifies “thinking as such” and “being as such.” This, Pippin insists, is the kernel of the “logic as metaphysics” thesis that has been so influential and so controversial in modern continental thought.

Against this backdrop, the paper highlights why Heidegger repeatedly singles out Hegel as the final consummation of Western metaphysics, a powerful system in which the Aristotelian principle that “to be is to be intelligible” is radicalized to the point where “nothing is left out.” If being is, by definition, determinacy, then “nothing” is not an alternative; it lapses into contradiction. Yet Heidegger strives to show, Pippin argues, how Hegel in effect presupposes the meaning of being as availability for conceptual articulation while never thematizing just how being itself—prior to or more foundational than any discrete determination—comes to be at all.

Heidegger insists that the metaphysical tradition, in seeking to know being by attending exclusively to beings and their determinate intelligible identities, forgets the question of being as such, and that this deep forgetfulness permeates Hegel’s project as well. Hence the point is not that Hegel claims there is nothing unknown, but that for him there is nothing unknowable in principle, and that this collapses all concerns about the finitude of thought into the question of how to expand conceptual articulation ever more systematically. According to Heidegger’s reading, all genuine questions of finitude, contingency, non-conceptual excess, or the ontological difference between beings and Being, become subordinated to the unstoppable unfolding of reason in Hegel’s conceptual totality.

Throughout the text, Pippin stresses that Heidegger, with all the philosophical power and acuity at his command, is neither offering a merely superficial critique of Hegel’s ideas nor dismissing them outright as some archaic mistake. Instead, Heidegger pursues a “step back,” that is, a retrieval of what remains “unthought” behind the very success of the Hegelian system. By naming Hegel the “culmination” of metaphysics, Heidegger implies that Hegel’s absolute idealism is the most advanced and self-aware version of Western thinking’s persistent treatment of being as rationally conceptualizable presence.

“Overcoming Hegel,” as Heidegger frames it, is synonymous with the attempt to open a new way for philosophy—or, perhaps, to free thinking from the onto-theological constitution that underpins all classical metaphysical constructions. In this sense, Pippin’s exposition reveals that Heidegger’s discussion of German Idealism, especially of the Kant–Fichte–Hegel line, forms a continuous thread in his Marburg and Freiburg years, from his 1929 lectures on the idealists to major texts like Kant and the Problem of Metaphysics, Identity and Difference, and The Fundamental Concepts of Metaphysics. Indeed, Heidegger’s repeated insistence that “Hegel must be overcome” shows just how seriously Heidegger took the Hegelian logic, and just how thoroughly he thought it defined the apex of the metaphysical approach he wished to leave behind.

Pippin’s account moves carefully through the detailed disputes that arise in this confrontation, underscoring that one of Heidegger’s major concerns is the relationship of thinking to sensibility, that is, to Dasein’s factical being-in-the-world, which is never reducible to a transparent logical structure. Hegel’s Logic, for Heidegger, sets up “thinking as such” as the final ground, the self-grounding ratio or logos that makes possible the very demarcation of any being as a determinate what. But Heidegger’s fundamental ontological inquiry reveals this assumption as itself in need of grounding, or better said, as dependent on something Hegel cannot fully integrate: namely, the irreducibly temporal, historically situated nature of Dasein, in which the meaning of being must manifest itself prior to any conceptual determination.

Put differently, if for Hegel the highest principle is the self-completing circle of reason, for Heidegger it remains vital to see that reason’s functioning owes itself to an ever-elusive happening of being that refuses to show up simply as another object for reason’s reflective gaze. Dasein’s finitude—exemplified in its relation to death, to anxiety, and to the null ground of its existence—points to dimensions of meaning that do not fit the standard model of conceptual determinacy. In sum, Pippin shows that Heidegger is not claiming simply that Hegel ignored the role of sensibility or that Hegel’s logic is inadequate for capturing certain “empirical” phenomena. Rather, Heidegger is insisting that what makes any conceptual articulation possible is Dasein’s already operative engagement with being, and that this operative engagement is not itself a conceptual or logical structure but something more fundamental that idealism, in Heidegger’s view, never truly questions.

In clarifying this tension, Pippin demonstrates both how rich Hegel’s logic of self-determining thought truly is and how perspicacious Heidegger’s demand that we ask about “the being of this thinking” remains. On the one hand, Hegel indeed dissolves simplistic dualisms between a thinking subject and an external or inert object; his notion of “pure thinking” is not the ephemeral content of a psyche but the development of intelligible determinations necessary for any being to be. On the other hand, Heidegger’s approach challenges the very attempt to subordinate all possible being to the necessity-structure of conceptual determinacy, charging that Hegel’s philosophical system gives no account of how Dasein’s finite thrownness, its historically shaped openness, or the sheer event of “there-is-being” enters into and underwrites such a system in the first place.

The question that hovers behind Pippin’s analysis is whether Hegel’s unwavering commitment to the identity of thinking and being forecloses the possibility of acknowledging that the clearing or unconcealment in which thinking grasps beings has an elusive ontological source that stands prior to—and is not exhausted by—conceptual formulation. If one accepts Heidegger’s argument, then the difference between Being and beings remains unthought in Hegel precisely because Hegel is the most thorough, culminating exponent of the metaphysical tradition, which always grasps being as the most general concept, rather than inquiring into its happening.

Yet, as Pippin artfully stresses, this does not simply mean Heidegger “wins” by uncovering an unbridgeable shortcoming. One might also wonder, from Hegel’s side, whether Heidegger’s emphasis on the pre-conceptual event of being lands him in a paradoxical space where all articulation of that event would itself be a further instance of conceptual claim-making, thus secretly re-enacting the Hegelian circle of reason. Pippin shows that, for Hegel, any purported critique of the Concept’s claim to universality still falls within the space of potential intelligibility—if one is to say something meaningful. This leads to further exploration of whether Heidegger can articulate the finitude of existence without resorting to the very conceptual categories he critiques, or whether the new beginning that Heidegger envisions remains entangled in Hegel’s dialectical logic. Both thinkers, as Pippin highlights, share the sense that philosophy must revisit and, in a sense, incorporate the history of previous thought in order to do its own work. Yet for Hegel, this leads to a culminating systematic science, while for Heidegger it leads to a preparatory “step back,” hoping to retrieve what the tradition has left unasked and to open a future path freed from the totalizing logic that has thus far defined Western metaphysics.

Throughout this challenging confrontation, Pippin emphasizes that the question of finitude—specifically, how to make sense of a thinking that claims unlimited scope and yet belongs to a finite being—occupies center stage. If Hegel’s route is to grant conceptual reason an infinite self-determination that, in its very structure, leaves nothing outside, Heidegger responds that the human being’s exposure to its own death, to groundlessness, and to the irreducible difference between “what it is” and “that it is,” prevents any neat assimilation of existence to pure conceptuality.

The significance of this debate extends far beyond historical or textual commentary: it touches on questions of modernity, technology, and the manner in which reason and metaphysics might (in Heidegger’s stark warning) lead to a dangerous forgetting of the ontological dimension in favor of an ever-expanding apparatus of conceptualization and control. Pippin’s thorough textual analysis includes Heidegger’s references to the Kantian idea of pure reason needing sensibility or intuition, the Schellingian notion of the “neither subject nor object” as ground, and the ways in which modern philosophy has wrestled with the consistent tension that arises when reason is claimed to be both a self-authorizing tribunal and, at the same time, a faculty inextricably embedded in history, language, embodiment, and mortality.

By illustrating the subtlety with which Heidegger does indeed read Hegel—beyond superficial accusations that Hegel simply equates all being with “mind”—Pippin makes clear how Heidegger recognizes that Hegel’s idealism is deeply opposed to subjectivist or “psychologistic” perspectives, and that Hegel regards the “subject” as the site at which logic is enacted, not an isolated center of consciousness. Nevertheless, Heidegger continuously presses whether Hegel’s identification of logic and being permits any recognition that a distinct mode of being belongs to the thinking subject, which is neither that of a material entity nor that of a purely conceptual structure but instead Dasein, defined precisely by the existential difference that the tradition labels finitude. In that sense, “radical finitude” emerges as the primary wedge Heidegger drives into the system of Hegel’s absolute idealism.

The question is whether or not Hegel’s reflections on “pure thinking thinking itself” leave room for the irreducible concreteness of “existence,” which cannot be turned into an object of conceptual knowledge without occluding its essential openness and possibility. Pippin’s portrayal thus frames a genuinely high-stakes contention: for Hegel, anything that claims to stand outside conceptual determinability effectively reduces to pure indeterminacy, a “nothing” that cannot be. For Heidegger, that “outside” is precisely where and how we must search for the meaning of being itself and thereby recognize the inexhaustible ground of its event-like disclosure.

In developing this storyline with attention to the texts, Pippin’s Idealism and the Problem of Finitude: Heidegger and Hegel not only clarifies an iconic philosophical dispute but also invites the reader to experience the mutual illumination that arises when Hegel’s Logic and Heidegger’s fundamental ontology are placed in direct conversation. The result is a far-reaching reflection on the nature of philosophy, on the structural conditions of intelligibility, and on the existential puzzle of how a finite being can encounter a seemingly infinite rational order. Far from being a mere historical overview, the paper plunges the reader into the conceptual core of idealism’s attempt to unify thought and being, and the subsequent insistence, shared by so many post-Hegelian thinkers, that modern philosophy must grapple with finitude in more radical ways than Hegel allows.

The question becomes whether the impetus for a self-grounding pure reason must inevitably ignore something essential about what we are—and about how the meaning of being emerges historically, poetically, or mysteriously, rather than simply coming into view as one more region available to conceptual categorization. With impeccable scholarship, Pippin unveils how both Hegel and Heidegger were inspired by Kant’s critical project, particularly by the idea that the conditions for knowledge—whether conceptual or intuitive—must be explored in a transcendental manner. Yet while Hegel extends and transforms this transcendental move into a systematic metaphysics, Heidegger tries to show that the relationship between thinking and being as presence is itself beholden to an ontological difference, leaving an inscrutable dimension unarticulated and, indeed, unarticulable in Hegel’s account.

The richness of this paper rests in Pippin’s ability to display the subtlety of Hegel’s claim that the Logic is not “merely” about thinking but about being as determinacy, combined with a lucid depiction of Heidegger’s contention that Hegel’s achievement—precisely in its visionary thoroughness—prevents philosophy from confronting the more primordial question of why there is being (determinacy) at all.

Readers come away appreciating that this clash over finitude is not a minor disagreement about the scope of epistemic certainty but a comprehensive divergence about the very shape and possibility of metaphysical reflection. The finitude that Heidegger thematizes—tied to time, language, history, and the event of unveiling—cannot straightforwardly appear as an object of Hegelian thought, yet Hegel would likely respond that Heidegger’s method of articulating this finitude draws on conceptual resources that lie inside the Concept’s domain after all. Pippin here explores the nuanced ways in which each philosopher might push back against the other, showing that this is not a one-sided dismissal but a significant and generative conflict at the heart of modern continental philosophy.

Idealism and the Problem of Finitude: Heidegger and Hegel is thereby a major resource for anyone invested in understanding how Kant’s and Hegel’s legacy was adopted, radically reinterpreted, and contested by twentieth-century existential and phenomenological movements. It underscores the still-unresolved question of whether reason can, in fact, be self-authorizing in the manner Hegel insists, or whether the irreducible finitude and historicity of Dasein forecloses any absolute completion of reason’s claims.

Those inclined toward Hegel will appreciate Pippin’s astute demonstration of the sheer depth and systematic coherence of the Logic, which is often misunderstood or caricatured. Those inclined toward Heidegger will benefit from seeing precisely why Heidegger considered Hegel the supreme example of the metaphysical forgetting of Being. And all readers, regardless of allegiance, will be confronted with the abiding philosophical mystery of how it is that “thought thinks being,” even though we cannot find a vantage point outside this interplay from which to justify its coherence once and for all.

In its unparalleled detail, this work by Robert B. Pippin thereby helps to illuminate an essential dimension of the modern philosophical inheritance, tracking how Hegel’s “absolute” stands or falls on the question of reason’s finitude, and explaining why Heidegger, though granting Hegel’s greatness, tirelessly seeks to show another path in which the very meaning of being is opened anew. The result is a study that places two of philosophy’s most formidable figures into sustained dialogue, pushes the boundaries of what philosophical reflection might achieve, and clarifies how both Hegel’s Logic and Heidegger’s fundamental ontology grapple with issues that remain at the forefront of contemporary debates: the possibility of ultimate intelligibility, the inseparability of existence from historical contexts, the role of death and anxiety in shaping human understanding, and the question of whether there is something about being itself that can never be reduced to logically governed determinations.

By uniting historical sensitivity, textual fidelity, and a willingness to engage with fundamental conceptual challenges, Pippin’s essay draws the reader through a wide array of interlocking issues—metaphysics, logic, phenomenology, existence, and finitude—inviting an encounter with the abiding tension in Western thought between the rational transparency that idealism holds out as a promise and the irreducibly hidden or concealed dimension that Heidegger elevates as the core of Dasein’s fundamental ontology.

Leave a comment