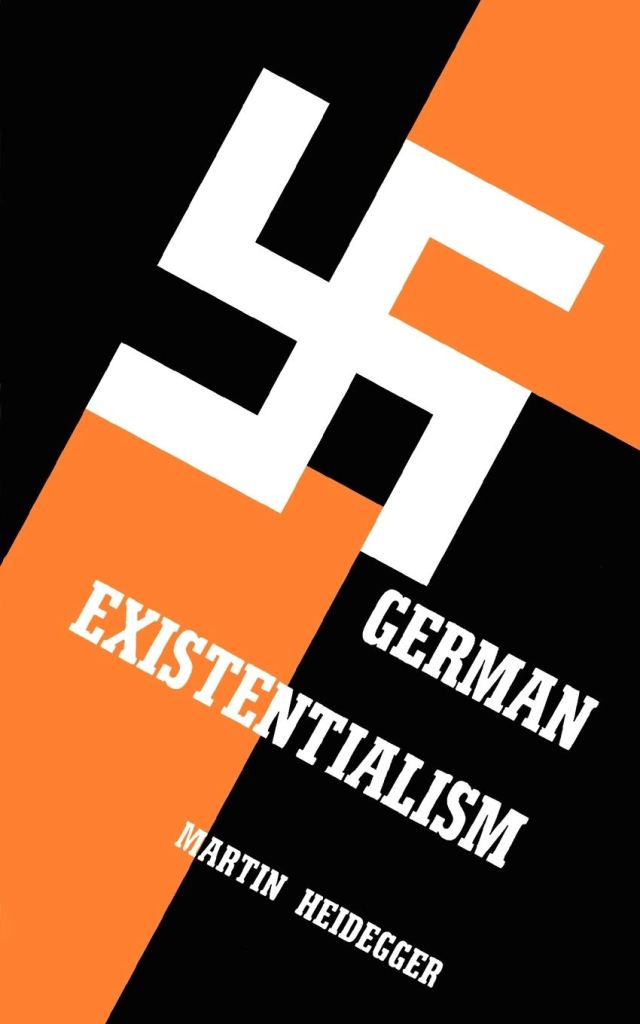

In this remarkable and deeply disquieting volume, published in 1965 by Philosophical Library and stretching across a mere sixty pages that nevertheless brim with historical significance, the reader is confronted with one of the most perplexing instances of philosophical genius entangled with political brutality. Titled simply German Existentialism, it purports at first glance to be a scholarly articulation of Martin Heidegger’s ideas on Being and Time, phenomenology, and existential philosophy, but it rapidly reveals itself as a charged anthology of his pronouncements and lectures from the period of National Socialism’s ascendancy in Germany. The text stands as an agonizing testament to the capacity of profound intellect to cleave itself to the most repugnant and destructive politics of the twentieth century. Heidegger, renowned for his probing investigations into the nature of Being, for his phenomenological debt to Edmund Husserl, and for the shattering possibilities hinted at in the existential lineage from Kierkegaard and Nietzsche, emerges here as a contradictory figure of towering philosophical imagination on the one hand, and a fervent Nazi partisan on the other. In so doing, this slim work foists upon the conscientious reader a jarring series of questions regarding moral responsibility, the potential complicity of metaphysical inquiry in political oppression, and the fragility of intellectual integrity in the face of historical cataclysm.

The anthology opens with a stark and sobering note: “On the day of German Labor, on the day of the Community of the People, the Rector of Freiburg University, Dr. Martin Heidegger, made his official entry into the National Socialist Party.” These words cast an immediate pall of unease over the entire text, because they place the revered philosopher in open alignment with Adolf Hitler’s movement. This is no peripheral act: it illuminates a period in which Heidegger, newly installed as Rector at Albert-Ludwig University in Freiburg, is revealed to have woven together Nazism’s virulent brand of German nationalism with his own existential-phenomenological thought. One senses at once the swirling tensions in that era, a time when the philosopher recast Being-in-the-world through the lens of a pseudo-metaphysical justification for Hitler’s violent policies. So forthright is the documentation here that it all but shatters the myth that Heidegger’s involvement with National Socialism was merely a naïve error or a limited lapse in judgment. Instead, one confronts the spectacle of Heidegger shaping existential metaphysics into a celebratory paean to the “Führer” and mobilizing his rhetorical brilliance to justify a brutalizing regime.

Among the many voices reacting to this unholy symbiosis of ideas stands Benedetto Croce, who rebuked his German contemporary, declaring: “This man dishonors philosophy and that is an evil for politics too.” Croce’s condemnation registers the sense of betrayal felt by many of Heidegger’s peers and colleagues, particularly because philosophy, in the grand tradition from Plato’s Academy through Kant’s transcendental critiques, is meant to stand above the fray of momentary political frenzy and serve a more universal quest for truth. And yet Heidegger, as the meticulously cited speeches and documents in German Existentialism reveal, chose to direct his formidable intellect into channels that loudly praised Hitler as the embodiment of Germany’s future reality and waged verbal warfare against what he labelled “uncommitted” scholarship or the “idolization of a landless and powerless thinking.” This text shows precisely how he situated the Nazi worldview within the existential project, calling the revolution “not simply the taking of power in the state by one party from another, but… a complete revolution of our German existence.” In that line alone, one perceives the scale of Heidegger’s complicity: he cast Nazism as a new beginning for Germany’s metaphysical destiny.

It is all the more disturbing because, in the appended speeches, Heidegger demands that students relinquish academic freedom in favor of discipline, labor service, and military training. He praises the Nazi book burnings—ominous purges that sought to excise so-called “Jewish-Marxist” influence from the intellectual life of the nation—and calls for the “binding ties” among teachers, students, and the Volk to be expressed through fervent pledges of loyalty to the Führer. The text even reproduces calls from the Freiburg student body urging the public to hand over “all books and writings that deserve burning,” thus underscoring Heidegger’s readiness to place the philosophical profession at the service of Hitler’s politics. The chilling synergy between his words in these addresses and the savage cultural upheavals that accompanied the early years of the Third Reich is unforgettably chronicled. One also sees that Heidegger’s forging of lofty spiritual talk about Being with the violent rhetoric of Nazi ideology did not remain an abstract exercise; indeed, the collection includes references to how Jewish professors were stripped of their teaching licenses, an early step in the broader racial persecutions that culminated in unimaginable atrocity.

Dagobert D. Runes, who compiled this anthology with the express aim of exposing what he calls the “utter confusion Heidegger created,” frames the text with an introduction condemning Heidegger’s attempt to graft existential metaphysics onto “the decadent and repulsive brutalization of Hitlerism.” Runes’s editorial voice does not withhold judgment, nor does he attempt a neutral academic discussion. Instead, he insists that no philosopher before Heidegger had ever so thoroughly betrayed the time-honored principle of philosophy as an impartial search for truth: from the Vedic sages to Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, and beyond, philosophers had presumably set themselves against the ephemeral lure of temporal power. Heidegger, in Runes’s eyes, is therefore unique in becoming an outright “spokesman for National Socialism,” an intellectual architect who recast abiding existential concerns about authenticity, being-toward-death, and angst into an unapologetic salute to Hitler’s new Reich.

The publication date of this anthology, 1965, is itself significant for intellectual history. More than two decades had passed since the collapse of the Third Reich, the revelations of concentration camps, and the subsequent philosophical reckoning that had tarnished Heidegger’s reputation. It predated the seismic wave of scholarship ignited in 1987 by Victor Farias’s Heidegger et le nazisme, which more broadly publicized and scrutinized the depth of the philosopher’s collusion with Hitlerism. Yet even in 1965, there had been attempts to reckon with Heidegger’s record. To see him singled out by Runes so vehemently, accompanied by reprints of actual speeches praising the Führer and instructions to subjugate academic freedom to the Nazi cause, signals that this text stands as an important prelude to the firestorm of debate that would eventually engulf Heidegger scholarship in the late twentieth century.

The reprinted introduction, the numerous official addresses given by Heidegger, and the ominous glimpses of how students were exhorted to book burnings and labor service, all unfold on the pages of German Existentialism with a powerful immediacy. One can glean the rhetorical style in which Heidegger glorifies “the tough reality of labor camps” as formative experiences of a new communal being, or how he argues that “academic freedom” must vanish under the new Reich in favor of strict, militant subordination. One sees too the moment he declares that “the Führer himself, and only he, is the current and future reality of Germany,” making a near-blasphemous leap from the existential notion of Being to the worship of Hitler. These documents lay bare how the quest for an authentic “Self-Assertion of the German Universities,” as Heidegger put it, was instrumentalized to ensure that academia would serve the Third Reich’s ideological aims. The text also references the dramatic public ceremonies—Heidegger attending dueling contests, praising the new order, speaking to crowds of unemployed workers under Nazi programs, and forging a pageantry that nestled seamlessly into Hitler’s grandiose visions of total mobilization.

Readers who approach this text for historical insight will discover it is both indispensable and profoundly disturbing. Its minimal length belies the labyrinth of questions it raises: How could an intellect so celebrated for subtlety and depth give itself over so fully to a regime founded on violence, racism, and persecution? To what extent was Heidegger’s philosophy—particularly his notions of Dasein, authenticity, and thrownness—mutated or exploited when turned into the service of National Socialist propaganda? Did his philosophical method prefigure or enable such political alignment, or does his participation represent a betrayal of his own deeper inquiries? Since these same philosophical writings, especially Being and Time, continue to influence contemporary continental thought, one wonders if such brilliance can truly remain unsullied by the atrocities undertaken by its author’s chosen political alignment. The anthology spares no one from these questions: it forces any reflective reader to grasp the unnerving possibility that even the loftiest inquiry into Being may be vulnerable to the temptations of historical fanaticism.

Critical responses to German Existentialism have been polarizing. One of the top reviews from the United States, written decades after the original publication, straightforwardly labels it as vital documentation showing how “a brilliant man can be profoundly evil.” Yet another review laments that the book is “grossly incomplete and poorly translated,” warning that it should be read only in conjunction with other contemporary texts and articles on Heidegger’s speeches from 1933–34. Even so, the reviewer concedes that its precedence, having been released more than twenty years before Farias’s exposé, renders it of rare bibliographic value. On the one hand, the anthology is no rigorous scholarly tome with commentary placed in calm neutrality; on the other, it is an essential historical artifact, a clarion call that sounded long before much of the broader philosophical community fully confronted the gravity of Heidegger’s Nazi involvement.

The significance of these controversies becomes all the more tangible when one notes the confluence of major philosophical influences on Heidegger—Kierkegaard’s existential pathos, Nietzsche’s radical reevaluation of values, Husserl’s phenomenological method—and sees how these influences were leveraged in the cause of Hitlerism. Heidegger’s debt to Husserl, and his subsequent betrayal of that venerable mentor (who was of Jewish heritage), testifies yet again to the moral abyss into which the Third Reich lured or cajoled many of Germany’s leading minds. A swirl of ironies emerges: here was a philosopher famed for claiming that the essence of Dasein is its capacity to take responsibility for its ownmost possibilities, yet he harnessed that conceptual apparatus to demand that students and professors alike subordinate themselves to the dictates of the Führer’s will. In the mirror of this anthology’s texts, one sees personal destiny and existential authenticity twisted into ciphers for ideological fervor.

Nor can one forget the tragic practical outcomes that these speeches helped normalize. The revoking of Jewish professors’ licenses, the celebratory calls for an ongoing “fight against Jewish-Marxist undermining of Germany,” and the enthusiastic endorsement of physical intimidation rituals such as duels and paramilitary sports all formed part of the local mise-en-scène at Freiburg University during Heidegger’s rectorship. It is both surreal and harrowing to consider that a philosopher often exalted for his insights into the question of Being simultaneously served as a herald for Hitler’s rhetoric and policy. Even the dimension details of this paperback volume—five inches by eight, a mere 0.14 inches thick, and weighing but 2.57 ounces—feel incongruous with the weight of the moral quandary it lays upon the intellect.

Thus, for anyone seeking to pierce the protective shell of pious reverence that still sometimes surrounds Heidegger’s name, German Existentialism stands as an unflinching exposé of the period in which he unmistakably pledged his philosophy, his rhetorical craft, and his moral credibility to one of the most violent regimes of modern times. And it is not simply the story of a personal misstep or an isolated, context-bound failing; it is the disquieting chronicle of how a metaphysical system that asks fundamental questions about human existence—questions that have shaped entire generations of existentialist and phenomenological thinkers—could be corroded from within by the allure of totalitarian propaganda. The presence of the now-famous “yellowish grey wolf” analogy, which lurks as a foreboding emblem in the book’s quoted excerpts, might stand in for Heidegger’s own transformation: one who howls fiercely, seemingly at one with the darkest impulses of the ideological pack, before returning to the philosophical domain with a show of contrition or metaphysical nuance.

The final measure of this anthology’s power is perhaps the sheer intensity of the reflection it demands from present-day readers, scholars, and students of philosophy. “A search for the meaning of Being,” as Heidegger once characterized philosophy, collides here with the unspeakable brutality of a dictatorship’s policies, all supported by his formidable intellect. The painful recognition is that no truth, no matter how abstemious or ostensibly pure, is guaranteed immunity from political seduction. If the perennial mission of philosophy has been to stand guard against falsehood, injustice, and folly, then Heidegger’s collusion sounds a warning: the greatest conceptual subtlety can be marshaled to sanctify the worst of deeds if the philosopher fails to guard the threshold of conscience. In line with Croce’s condemnation, one sees how Heidegger’s betrayal might ultimately be “an evil for politics” by corrupting the practice of reason and giving license to the tyranny of unbridled will.

All of this is preserved in a paperback that, in the marketplace of books, might occupy a distant rank—number 5,527,674 in overall sales, number 1,247 in German Literary Criticism, and number 25,962 in Literary Criticism & Theory—but that endures as a crucial record for anyone grappling with the shadow that can fall across an intellect of the highest caliber. And so, in reading or rereading German Existentialism, one does not merely plunge into an academic debate about the nuances of Dasein or the complexities of phenomenological method. One encounters an unvarnished confrontation with the moral hazards of intellectual life, bearing witness to the cataclysmic union of existential philosophy and state terror. Not merely an historical curiosity, it is a cautionary piece of evidence that compels us to ask whether the pursuit of Being can become, when suborned to extremist ideology, an engine of cruelty.

In that regard, this volume is both philosophical and anti-philosophical: it documents ideas that claim to investigate the depths of Being yet serve, in these pages, to glorify a monstrous government’s ambitions. The unsuspecting student of Heidegger might open it naively, seeking clarity about existentialism’s relevance to modern experience, only to discover a wellspring of disturbing pronouncements celebrating Hitler’s revolution. Here, in the starkest black and white, is a man who wrote Being and Time, who taught with Husserl and drew from Nietzsche, extolling the virtues of Nazi labor service and proclaiming that “the Fuhrer himself, and only he, is the current and future reality of Germany.” It is not a portrait easily dismissed or compartmentalized. No bullet points, no subheadings, no ephemeral disclaimers can soften its impact. The best one can do is face the echo of Runes’s condemnation, the harshness of Croce’s judgment, and the echoing resonances of countless other thinkers who recognized the betrayal: the sum total forms an unforgettable lens on the precarious line between sublime philosophical insight and abject complicity in atrocity.

This is German Existentialism by Martin Heidegger, as compiled and introduced by Dagobert D. Runes—a controversial, indispensable, and profoundly vexing book. From the vantage point of posterity, its significance has only magnified. It is not an easy read; it is not a comfortable read; but it is a necessary one for those who strive to understand the swirling depths where high-minded inquiries into human existence might descend into the darkest corridors of political fanaticism. The resonance of these pages remains unshakable, reminding us that no philosophical genius, however brilliant, is immune to the moral catastrophes that can unfold when the quest for truth is sacrificed to the illusions of power. It is here, in the stark testimony of Heidegger’s own words and the condemnation they provoked, that the essential tragedy of this most controversial philosopher finds its clearest and most haunting expression.

Leave a comment