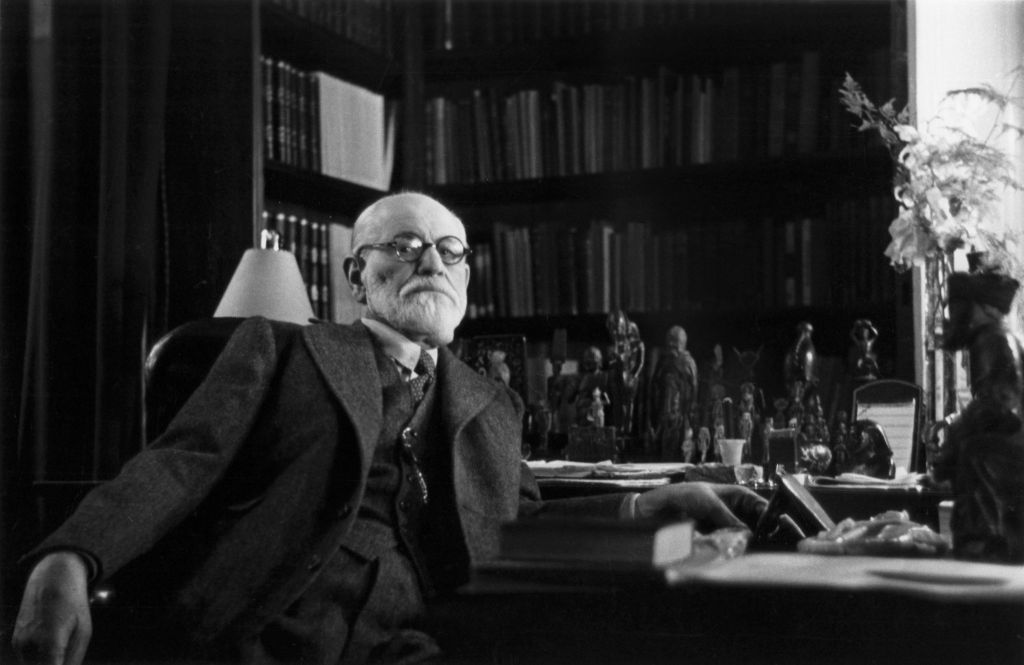

Few works in the field of psychology have endured with as much intellectual consequence, as much capacity to provoke thought and reflection, and as much historical gravitas as Sigmund Freud’s Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis. The present edition, translated by G. Stanley Hall, is not merely a straightforward rendering of Freud’s original German text, but as a subtle, painstakingly accurate transposition of a series of groundbreaking lectures first delivered between 1915 and 1917 at the University of Vienna—a formative epoch when the world was torn by war, when the established certainties of rationalist thought were under siege, and when the inner life of the human being demanded a more painstaking form of interpretation.

Through these lectures, Freud, by then a figure advanced in his career, seeks to unravel the vast complexity of our mental experience, providing an ambitious yet orderly summation of ideas that had already reverberated powerfully through the emerging scientific discipline known as psychology. In them, we discover a mature Freud reflecting upon three decades of labor, contending with both allies and adversaries, and wrestling with the immediate intellectual heritage that had grown up around his discoveries. The result is a text that not only displays his interpretive genius, but also reveals a deeply human engagement with the most elusive aspects of the mind, as well as a willingness to revisit, defend, and at times refine the basic propositions that ushered in the psychoanalytic revolution.

Here, Freud’s language does not remain confined to the sanctified hush of the clinical office or the cloistered study hall, but makes itself accessible, at least in form, to an attentive and curious audience, including those not already indoctrinated into the mysteries of psychoanalysis. At the same time, what he offers is no simplification that robs his theory of depth; rather, this collection represents a careful introduction intended to show precisely how psychoanalysis conceives of the human subject as a ceaseless interplay between the conscious and unconscious realms.

We encounter, in these lectures, Freud’s enduring attempt to map the topography of the psychic apparatus: to demonstrate that error and mishap, whether through slips of the tongue, bungled actions, or forgotten words, are not random phenomena of everyday life, but windows into the hidden, unconscious desires and repressions that influence our thoughts and guide our behavior. We encounter, too, a lucid survey of his theory of dreams—not as meaningless nocturnal hallucinations, but as complex symbolic expressions of unconscious desires, shaped by forces that originate in childhood and remain buried beneath the superficial layers of consciousness. We are led gradually toward Freud’s general theory of neuroses, with its frank acknowledgment of sexual desire as a key determinant in the psychic conflicts and sufferings of the individual. Though some claims presented here would later be modified or complemented in Freud’s subsequent lectures and writings, what we find in this work is a still-coherent, classically Freudian universe of ideas, one that had, by the time of these lectures, achieved a lasting cultural impact and ignited fiery debates that would persist and transform the psychological landscape for generations.

Yet these lectures are not only theoretically or historically significant; they are vital documents capturing Freud in the midst of a dynamic intellectual milieu. G. Stanley Hall’s translation gives English-speaking readers a trustworthy version of Freud’s voice. These lectures stand out for their frankness, accessibility, and disarming clarity. Freud acknowledges the difficulties and limitations of psychoanalysis, its method, and its results. He expresses these limitations with a directness that can still astonish modern readers, who are accustomed to clinical reserve or scientific diffidence. Instead of a stringently academic tone, he adopts an almost conversational approach, one that seems informed by his many years of addressing patients, students, and skeptical outsiders.

We perceive the complexity of the historical context in which psychoanalysis emerged, when rival theories and intellectual frameworks—some emanating from within Freud’s own circle, others from distant scientific traditions—jostled for authority. Freud’s genius lies not only in the originality of his concepts, but in his willingness to situate them within an ever-widening sphere of disciplines, including anthropology, literature, religion, aesthetics, and the broader humanities. These lectures helped bridge clinical insights and cultural analysis, making psychoanalysis into a kind of universal interpretive key to human behavior and creativity. The psychoanalytic lens, as Freud presents it, does not remain confined to patients suffering from hysteria or phobia; it expands outward to illuminate the hidden motivations behind everyday errors, private fantasies, and even collective cultural achievements.

There is a distinctly retrospective quality in these lectures. Delivered in his sixtieth year, Freud looks back on the arc of his work, recognizing that psychoanalysis had moved from its initial, controversial beginnings to a place of undeniable if contested prominence. He is aware that his ideas, once greeted with incredulity, have influenced literature, history, biography, education, ethics, and the interpretation of myth and religion. Freud observes how deeply the concept of the unconscious has taken root, and he cannot help but reflect upon the odium it has brought him in certain circles, the misunderstandings it has engendered, and the ways in which his most original pupil-interpreters, notably Adler and Jung, have diverged and established their own schools.

In these lectures, he also acknowledges what has been gained: a richer understanding of the psyche, the forging of a technique for treating neuroses, and the establishment of a new prophylaxis of mental health. The emphasis on the role of sexuality in psychic life remains a cornerstone, one that had and continues to have unsettling implications. As Hall remarks, Freud confronted a formidable social and academic resistance to these theories, a resistance that emanated from moral taboos and entrenched intellectual orthodoxies. Nevertheless, the lectures remain confident in their interpretation, unwavering in their defence of psychoanalysis as a science that reveals previously unknown mental mechanisms and the causal laws that govern the seemingly incoherent or arbitrary aspects of mental life. Dreams, slips of the tongue, and small everyday errors are reclaimed as meaningful fragments of a broader psychodynamic process.

Such richness of content and approach implies that the lectures, widely read and translated, quickly became canonical in psychoanalytic literature. They exhibit Freud at his most perspicacious: thoroughly steeped in clinical experience, gently guiding his audience away from simplistic notions of mental functioning, and consistently aware that the unconscious itself resists direct scrutiny. Instead, it must be approached indirectly, through dreams, symptoms, and parapraxes—those psychical formations that emerge as compromises between conflicting impulses. Reading these lectures is therefore an initiation into a method of interpretation that relies less on straightforward explanation and more on a subtle, context-sensitive excavation of hidden meanings. Through these pages, the reader not only learns psychoanalysis, but also practices, in a sense, the central gesture of psychoanalysis: translating manifest surface details into latent underlying structures of thought and emotion. This practice, Freud insists, is what yields profound introspective enlightenment, not just for the trained analyst in a consulting room, but for any thoughtful individual willing to observe the interplay of psychological forces in their own interior life.

One must also consider the cultural and scholarly environment of the lectures as Freud delivered them. The war ravaging Europe formed a backdrop of tension, uncertainty, and violence, inflecting Freud’s words with the gravity of a time in which old certainties had crumbled. Psychoanalysis itself had already undergone schisms, losing Adler and Jung, among others, and was struggling to define its core truths and its rightful place in the scientific community. Freud’s conscious decision at this juncture to present a comprehensive outline of psychoanalysis to a lay audience is remarkable. It suggests that he believed psychoanalysis had something universal to say, something that could not remain confined to a handful of specialists. This openness is evident in how he frames the dream theory, in how he accounts for the neuroses, in how he contextualizes the nature of psychological error. Far from parochial, Freud’s vision in these lectures attempts to place psychoanalysis into the vast current of humanistic inquiry, casting light on diverse subjects from the most personal intimate struggles of libido and aggression to the grand sweep of cultural phenomena.

Yet these lectures should not be read as static dogma. Freud himself later revisited some of the positions he adopted at this time, issuing the New Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis in 1932. By then, the analytic movement had evolved and Freud had integrated fresh data into his conceptual framework. Nonetheless, the original lectures remain a cornerstone, for they present that crucial synthesis and recapitulation so essential to those who wish to understand the genesis and structure of psychoanalysis. They show Freud grappling with the complexities of unconscious mental life and exploring methods of treatment that sought not just to alleviate symptoms, but also to reveal the underlying psychical conflicts that generate them. Hall’s introduction, as well, provides a valuable contemporary perspective, highlighting how psychoanalysis had already stirred the interest of scholars outside the narrow realm of laboratory psychology and charting its growing influence on fields as distant as literature, sociology, and theology.

As a book Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis offers much more than a historical curiosity or a textbook compendium of Freudian theory. It stands as a rich intellectual presentation made from clinical experience, cultural observation, theoretical speculation, and philosophical inquiry. It draws the reader into a process of reflection on what it means to be human: how hidden motives shape our conscious choices, how our earliest childhood experiences continue to operate in the seemingly rational decisions of adulthood, how symbols and dreams encode psychic material that would otherwise remain inaccessible. It invites an ongoing engagement with the idea that there is, at our core, something elusive, dynamic, and powerful that resists easy categorization—a depth that demands interpretation. Indeed, the philosophically inclined reader will find in these pages a sustained meditation on the nature of subjectivity, the tension between reason and desire, and the intricate ways in which culture and psyche interpenetrate. Freud’s lectures remind us that human consciousness is not a fully transparent glass vessel, but a vessel of layered opacity, where insight, understanding, and healing must be sought through patient, methodical acts of interpretation.

The result is a work whose scope and ambition remain formidable even after a century of further developments in psychology and the human sciences. Its influence, while contested, has not diminished. Instead, these lectures persist as a gateway into a realm of thought that transformed how we understand ourselves, our relationships, and the world we inhabit. The form of the lectures—originally spoken, subsequently revised, now widely read—gives them an immediacy and urgency that many other theoretical texts lack. Though they have become classics, they have not lost their power to challenge complacent assumptions about the unity of the self or the transparency of conscious will. In reading them, one embarks not merely upon an intellectual journey, but a subtle venture into the recesses of the psyche, guided by Freud’s unwavering conviction that truth, however discomforting, is to be found by listening attentively to the mind’s own spontaneous formations. If one acknowledges that the foundation of psychoanalysis rests upon a method of interpretation, then these lectures are its foundational text, bearing witness to the evolutionary moment when Freud’s ideas, previously scattered among specialized treatises and clinical monographs, were given shape as a coherent and accessible system.

It’s difficult to fully convey the density of the text itself. Yet it is sufficient to affirm that this is no ordinary work. It is a comprehensive path through which one must pass to grasp the conceptual and clinical achievements of Freud, an intellectual edifice that celebrates the complexity of mental life and encourages the reader to probe beneath the surface of daily experience. To describe it simply as an historical document or a psychological treatise would be to diminish its philosophical richness. The lectures transcend their epoch, urging us to recognize that under the veneer of rationality and civilization lies a potent domain of unconscious processes, and that by studying this domain we gain the chance to understand ourselves more deeply. Its pages grant us the privilege of following Freud as he constructs and solidifies one of the most influential frameworks for understanding the human mind, and as he does so with that mixture of rigor, daring, and humanity that made him a central figure in the canon of modern thought.

Leave a comment