H. J. Paton’s Kant’s Metaphysic of Experience is a monumental effort to provide what has long been a glaring omission in the landscape of Kantian scholarship—a thorough, sentence-by-sentence commentary on Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason that does not merely engage with Kant’s text but seeks to elucidate its meaning with precision and rigor. It is an ambitious attempt to counter the “scandal” that, over a century and a half after the original publication of Kant’s work, no commentary of sufficient depth and detail has emerged to match the monumental stature of Kant’s text, akin to the commentaries on Aristotle or Plato that have withstood the test of time.

Paton’s approach is not to present a mere gloss or general commentary, but to delve into the intricate complexities of Kant’s arguments, particularly those passages where the language and conceptual density reach their peak. By dissecting the text almost sentence by sentence, Paton addresses the specific linguistic and philosophical challenges that have led many students and even seasoned scholars to stumble. The precision with which Paton handles these difficulties is a reflection of his belief that understanding Kant’s Critique requires an engagement not only with the broad strokes of his philosophy but also with the exacting details that Kant himself deemed essential.

This commentary does not shy away from the intricacies of the Transcendental Deduction or the Analogies of Experience—sections that have historically been considered some of the most impenetrable in the history of philosophy. Paton’s detailed exegesis in these areas displays his belief that Kant’s philosophy forms a coherent and consistent whole, and that the apparent contradictions or obscurities in the text often arise from misinterpretations or from reading Kant’s sentences in isolation rather than as part of a systematic argument.

While Paton is fully aware of the potential drawbacks of his method—such as the danger of overwhelming the reader with detail or losing sight of the broader argument—he consciously chose this path because he was convinced that it is only through such meticulous analysis that one can truly grasp the architectonic of Kant’s thought. The potential for repetition is acknowledged but deemed necessary, particularly because of the recursive nature of Kant’s argumentation, where key concepts are revisited and refined as the Critique progresses. Paton provides the reader with the tools to navigate these repetitions, suggesting that once a reader has a firm grasp of the details, they can focus on the general interpretation and critique laid out in the later chapters of his commentary.

Paton’s work is distinguished not only by its rigorous exegesis but also by its critical stance towards other interpretations, particularly those that have sought to fragment Kant’s work into a patchwork of disjointed doctrines. Paton rejects the notion that the Critique is a mosaic of passages written at different times and artificially stitched together. Instead, he argues for the unity of Kant’s thought, a unity that can be discerned only when the Critique is approached as Kant intended—as a coherent, if difficult, whole.

This unity is not merely an abstract ideal for Paton; it is the basis upon which the entire commentary rests. He refutes in detail the patchwork theory, not by dismissing it out of hand, but by demonstrating, through careful analysis, how the Transcendental Deduction and other key sections of the Critique can be read as integral parts of a single argument. In doing so, he challenges the reader to see beyond the superficial contradictions and to engage with the deeper, underlying logic of Kant’s philosophy.

Paton’s commentary is also a critique of the broader trends in Kantian scholarship. He expresses his discontent with the bulk of what he terms Kantliteratur, much of which he finds either misleading or simply unhelpful. While he acknowledges these kind of contributions, he does not hesitate to express his disagreements, particularly when he feels that such interpretations obscure rather than illuminate Kant’s meaning. Paton’s own translations of key passages are crafted with an eye towards preserving the nuances of Kant’s original German, while also making the text accessible to those who may not be fluent in the language.

The commentary is not merely an academic exercise but a labor of love, driven by a deep conviction in the enduring value of Kant’s philosophy. Paton believed that Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason offers insights that are not only of historical interest but are of profound significance for contemporary philosophy. He was particularly critical of the modern tendency to dismiss Kant’s arguments as outdated or irrelevant, arguing instead that Kant’s thought contains truths that are still of vital importance and that have yet to be fully appreciated by many of his critics.

Ultimately, Paton’s work is a challenge to the reader. It is an invitation to engage with Kant’s Critique not as a relic of the past but as a living text, one that demands careful and sustained attention. For Paton, the goal of the commentary is not simply to explain Kant but to empower the reader to read Kant intelligently and critically, to see beyond the myriad interpretations that have accumulated over the years, and to confront the Critique on its own terms. In this way, Paton’s commentary is not just a guide to understanding Kant; it is a call to re-engage with one of the most important works of modern philosophy with fresh eyes and a renewed sense of purpose.

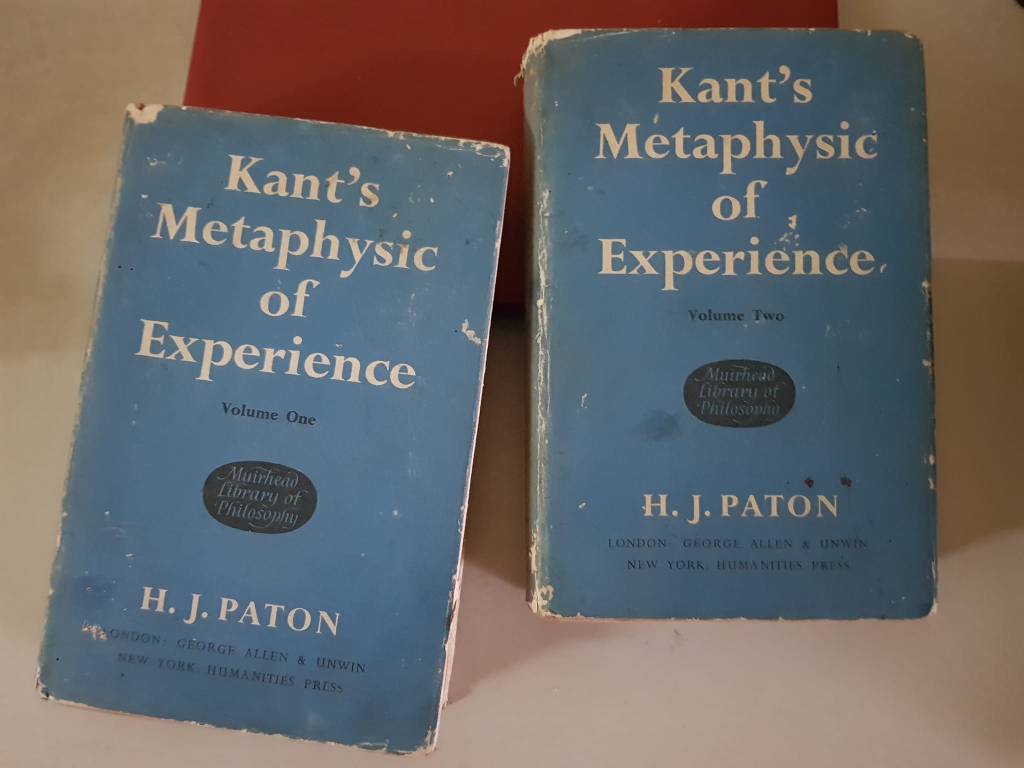

Herbert James Paton (1887 – 1969), widely recognized as H. J. Paton, was a distinguished Scottish philosopher whose academic contributions and public service left a lasting impact on both the intellectual and political landscapes of the 20th century. Educated and later teaching at prestigious institutions such as the University of Glasgow and Oxford University, Paton was a leading authority on the philosophy of Immanuel Kant. His seminal works, including Kant’s Metaphysic of Experience (1936) and The Categorical Imperative (1947), continue to be essential references in Kantian scholarship.

In addition to his academic achievements, Paton played significant roles during both World Wars, working within British intelligence and engaging in diplomatic efforts that shaped post-war Europe. Notably, he served as a member of the British delegation at the 1919 Versailles Peace Conference, contributing to the resolution of the Polish settlement, which he later documented in the six-volume History of the Peace Conference of Paris.

Paton’s career at Oxford began in 1911 as a fellow and praelector in classics and philosophy at Queen’s College. He held several key positions, including serving as Dean of the College and as Junior Proctor. In 1927, he was appointed Professor of Logic and Rhetoric at the University of Glasgow, where he also served as Dean of the Faculty of Arts. Ten years later, he returned to Oxford as White’s Professor of Moral Philosophy and a Fellow of Corpus Christi College, a position he held until his retirement in 1952.

Beyond his philosophical endeavors, Paton was deeply engaged with the political concerns of his native Scotland. His final book, The Claim of Scotland (1968), is a thoughtful exploration of Scotland’s constitutional position and a compelling argument for a greater recognition of its sovereign rights, reflecting his lifelong commitment to both intellectual rigor and national identity.

Leave a comment