Sculpture by Johann Gottfried Herder, translated by Jason Gaiger, is an extraordinary contribution to the annals of aesthetics, particularly in the context of 18th-century thought. In this dense and highly intricate work, Herder navigates the turbulent intellectual waters between the rationalist impulses of the Enlightenment and the burgeoning sentiments of Romanticism, offering a meditation on the nature of sculpture and the broader implications of sensory experience. Herder’s text, long esteemed in its original German as a seminal piece in the study of aesthetics, now finds new life and accessibility in Gaiger’s nuanced English translation, which does justice to the original’s complexity.

Herder’s exploration of sculpture is far more than a mere treatise on the art form, it is a philosophical excavation of human perception, sensation, and the embodiment of aesthetic experience. Central to Herder’s thesis is his challenge to the ocular-centric paradigm that had dominated Western thought since Plato, a critique that insists on the primacy of tactile engagement in the appreciation of sculpture. For Herder “the eye that gathers impressions is no longer the eye that sees a depiction on a surface; it becomes a hand, the ray of light becomes a finger, and the imagination becomes a form of immediate touching.“

Herder situates his discussion of sculpture at a critical intersection of classicism and romanticism, drawing extensively from classical sculptures while simultaneously foregrounding the historicity and temporal situatedness of both art and the senses. This dual emphasis not only anchors his discourse in the tangible reality of classical forms but also imbues it with a sense of historical consciousness that is emblematic of the Sturm und Drang movement to which Herder significantly contributed. In Sculpture, Herder is preoccupied with the differentiation between painting and sculpture, a dichotomy he unravels with an acute sensitivity to the limitations and possibilities inherent in each medium. Painting, dominated by the visual, offers a representation confined to a surface, whereas sculpture, through its three-dimensionality, invites a more embodied, tactile engagement that Herder believes is more authentic to the human experience.

What makes Herder’s analysis particularly compelling is his interdisciplinary approach. He joins together a vast array of sources, including classical mythology, Norse legend, Shakespearean drama, and Biblical narratives, to demonstrate the multifaceted nature of sculpture and its reception across different cultures and epochs. This breadth of reference underscores Herder’s commitment to understanding art not merely as an isolated aesthetic phenomenon but as a crucial component of cultural and historical discourse. His work anticipates many of the key debates in modern and contemporary art theory, particularly those concerned with the politics of perception and the sensory dimensions of aesthetic experience.

Herder’s critique of the hegemony of vision is not merely a theoretical proposition but is rooted in his own experiences of viewing sculpture. His travels across Europe, detailed with great care in the book’s introduction, allowed him to encounter some of the most renowned collections of classical sculpture, from the galleries of Versailles to the sculpture gallery in Mannheim. These encounters were formative, not just in the evolution of his thoughts on aesthetics, but also in the way they compelled him to reassess his previous understandings of sensory perception. Herder’s physical engagement with these works—his movement around them, his observations of light and shadow upon their surfaces, and his reflections on their forms—are all meticulously recorded in his writings, contributing to a rich phenomenological account of sculpture that remains strikingly relevant today.

Gaiger’s translation of Sculpture is accompanied by an extensive introduction that not only situates Herder’s work within the broader context of 18th-century aesthetic theory but also elucidates the philosophical underpinnings that inform Herder’s approach. Gaiger highlights the influence of Herder’s teachers, Immanuel Kant and Johann Georg Hamann, both of whom left indelible marks on Herder’s intellectual development, albeit in contrasting ways. Kant’s emphasis on rationality and universal principles is tempered in Herder by Hamann’s insistence on the significance of feeling, language, and historical context. This tension between rationalism and sensualism is evident throughout Sculpture, where Herder seeks to reconcile these divergent influences in a manner that acknowledges the complexity of human experience and the nuances of artistic creation.

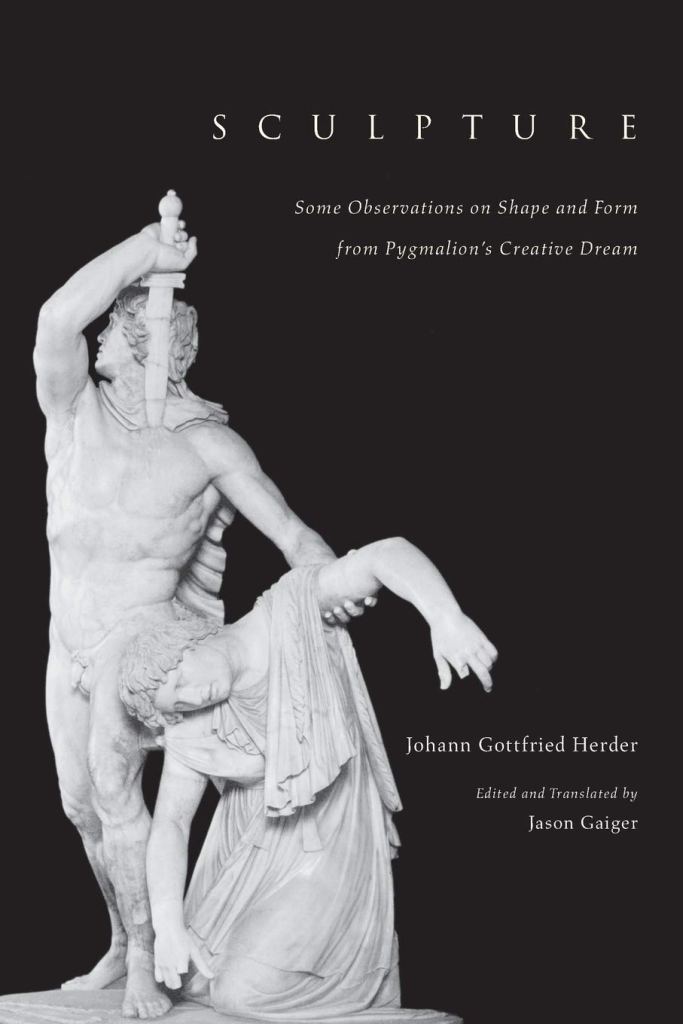

Moreover, Gaiger’s annotations provide crucial insights into the specific sculptures discussed by Herder, many of which are reproduced in the text, allowing readers to engage directly with the visual material that shaped Herder’s thoughts. These illustrations serve not only as visual aids but also as focal points for the reader’s own sensory engagement with the text, reinforcing Herder’s argument that the appreciation of sculpture demands more than just visual cognition—it requires an embodied, tactile interaction that bridges the gap between viewer and object.

Sculpture: Some Observations on Shape and Form from Pygmalion’s Creative Dream is, therefore, a work of profound philosophical import, one that challenges its readers to rethink the ways in which they perceive and engage with the world around them. Herder’s insistence on the historicity of the senses, his critique of the privileging of vision in aesthetic theory, and his passionate advocacy for a more embodied form of perception all contribute to a text that is as revolutionary today as it was in the 18th century. Gaiger’s translation ensures that this seminal work is now accessible to a wider audience, inviting contemporary readers to participate in Herder’s ongoing conversation about the nature of art, sensation, and human understanding. The book stands as a testament to the enduring relevance of Herder’s thought and his ability to anticipate and shape the trajectory of aesthetic theory long after his own time.

Leave a comment