Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason, first published in 1781 and subsequently revised in 1787, represents a seminal contribution to the landscape of Western philosophy. As one of the most challenging yet influential works ever produced, it serves as a profound investigation into the nature of human cognition, knowledge, and the limits of reason itself. Kant’s philosophical venture fundamentally reconfigures traditional metaphysical and epistemological frameworks, setting the stage for modern philosophical discourse.

In crafting this magnum opus, Kant engages critically with the prevailing philosophical currents of his time, particularly the empiricism of John Locke and David Hume, and the rationalism of Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. His goal is not merely to address the limitations he perceives in these systems but to offer a novel perspective that reconciles and transcends their respective strengths and weaknesses. Kant’s approach is radical in its insistence that our knowledge of the world is not a passive reflection of external reality but is actively shaped by the structures inherent in human cognition.

At the heart of Kant’s argument is the distinction between a priori and a posteriori knowledge. The former, according to Kant, is knowledge that is independent of sensory experience, while the latter is derived from it. This distinction becomes crucial in understanding Kant’s innovative concept of the “synthetic a priori.” Unlike the empiricists, who asserted that all knowledge is grounded in experience, and the rationalists, who claimed that knowledge can be attained through reason alone, Kant proposes that there are judgments which are both informative (synthetic) and known independently of any particular experience (a priori). This position seeks to demonstrate how certain fundamental truths about the world can be understood to be necessary and universal, yet still informed by empirical data.

Kant divides his critical examination into two main sections: the “Transcendental Aesthetic” and the “Transcendental Logic.” The “Transcendental Aesthetic” delves into the nature of human sensibility, exploring the a priori forms of intuition—space and time—that structure all possible experiences. According to Kant, these forms are not attributes of objects themselves but rather the lenses through which we perceive and organize sensory data. Space and time, therefore, are integral to how we experience the world, yet they do not exist independently of the perceiving subject.

The “Transcendental Logic” is more complex and is further divided into the “Transcendental Analytic” and the “Transcendental Dialectic.” The Analytic focuses on the role of concepts and categories in shaping our knowledge. Kant argues that understanding involves applying pure concepts of the understanding, such as substance and causality, to the sensory data provided by our intuitions. These concepts are necessary for the possibility of experience and are universally valid. The Dialectic, on the other hand, critiques the misuse of reason when it attempts to extend beyond empirical experience. Kant addresses the fallacies inherent in traditional metaphysical arguments, particularly those that attempt to assert knowledge about things-in-themselves—entities beyond the reach of human cognition.

Kant’s critique is not only a defence of his own philosophical position but also a thorough examination of various alternatives. He critiques “dogmatism,” which he associates with the metaphysical systems of his predecessors, arguing that they make unwarranted claims about the nature of reality without acknowledging the limits of human cognition. Kant also engages with skepticism and empiricism, presenting his theory as a way to preserve the certainty of scientific knowledge while accommodating the possibility of human freedom and autonomy.

The Critique of Pure Reason has left an indelible mark on philosophy. It has influenced subsequent philosophical movements, including German Idealism, existentialism, and analytic philosophy. Figures such as Johann Gottlieb Fichte, Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling, and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel further developed Kantian themes, each expanding or critiquing his ideas. Later philosophers, including Martin Heidegger and Ludwig Wittgenstein, engaged deeply with Kantian concepts, demonstrating the enduring relevance and complexity of Kant’s work.

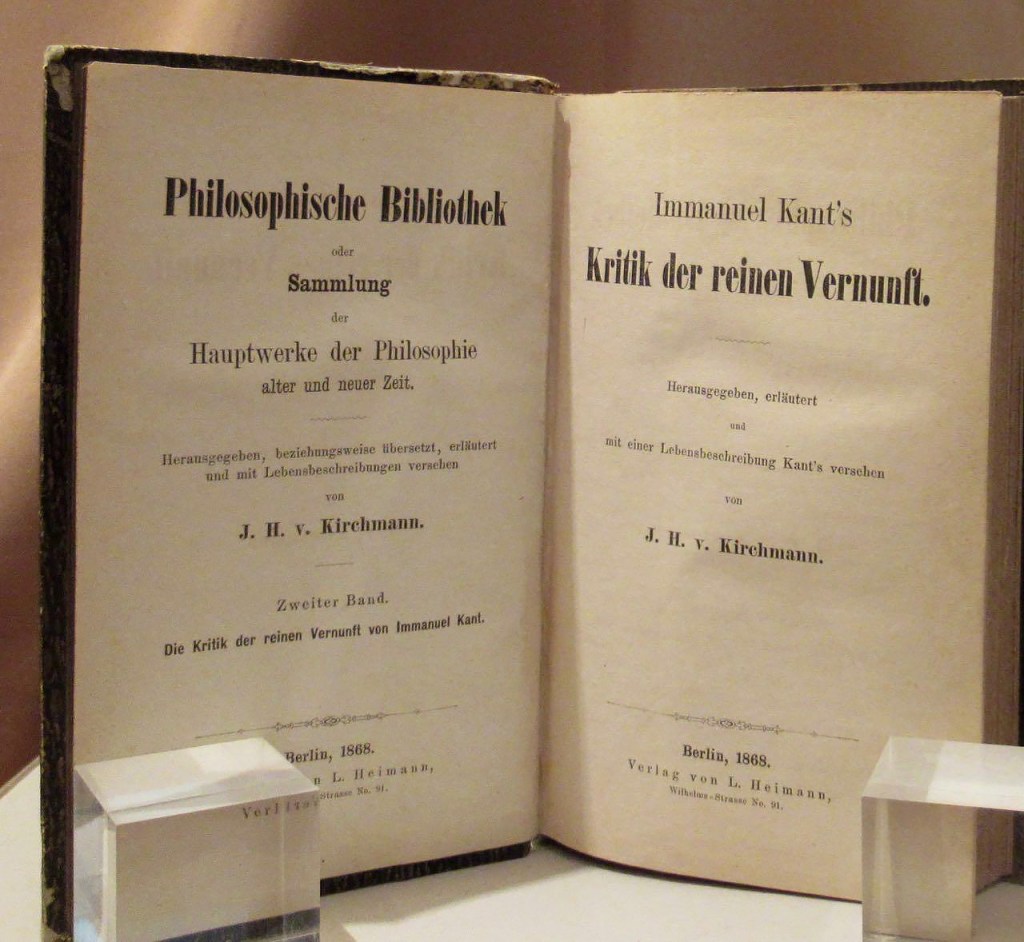

Translations of Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason have varied significantly, reflecting the challenges of rendering Kant’s intricate arguments into other languages. Notable translations include those by J.M.D. Meiklejohn, Norman Kemp Smith, and Werner S. Pluhar, each providing unique insights into Kant’s text. These translations are accompanied by extensive editorial notes, which help elucidate Kant’s dense arguments and the historical and philosophical context in which he wrote.

Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason is a profound exploration of the nature of human knowledge, challenging established metaphysical and epistemological paradigms. Kant’s innovative approach, particularly his concept of the “synthetic a priori,” redefines the relationship between reason and experience, offering a framework that continues to shape and inspire philosophical inquiry to this day.

Leave a comment